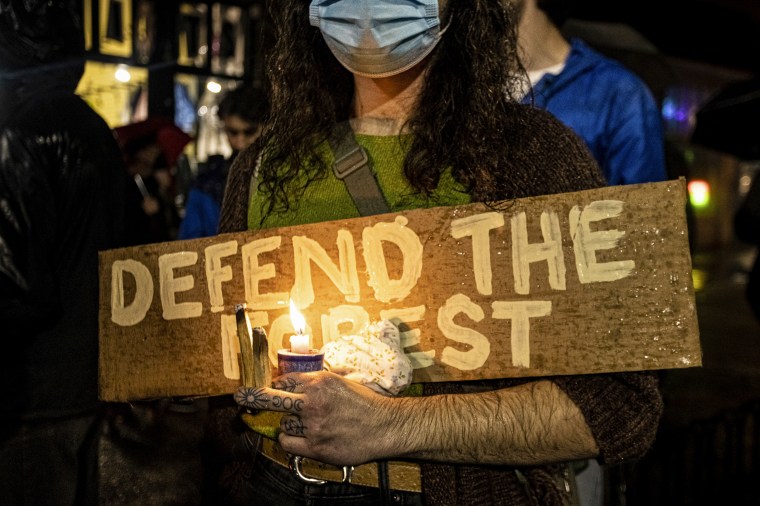

Last month’s killing of a nonbinary activist known as “Tortuguita,” who was shot during an occupation protest in Atlanta’s South River Forest, marked the first police killing of a demonstrator in the history of the U.S. environmental movement.

Police entered the forest on Jan. 18 after months of tension with activists, who had camped out in the area. Tortuguita was shot and seven others were arrested. It was the second police raid that resulted in arrests in about a month.

The Georgia Bureau of Investigation has said Tortuguita shot and injured a state trooper before officers returned fire. No body camera footage of the shooting is available, according to the bureau.

Lawyers for the family of Tortuguita, whose full name is Manuel Esteban Páez Terán, are questioning the police account of the shooting and say the GBI has not answered the family's questions about the shooting.

"We have contacted them through every channel we have available to us. We have gotten no response, no offer of sharing information with the family," said Jeff Filipovits, an Atlanta-area civil rights attorney, in an interview. "They want to know what happened to their child."

Occupation protests have been a staple of environmental activism for decades, but the one in Atlanta was different. Where police had often been intermediaries in previous protests, in Atlanta they acted as opponents whose own interest — a developmental project for a police complex — was a central part of the protest.

“There’s a long history of law enforcement confronting direct-action environmentalist activists and those confrontations turning hostile,” said Keith Woodhouse, an assistant professor at Northwestern University who wrote a book about radical environmental activism. “The huge difference is that one of these activists was shot and killed, and that is, I think, unprecedented in the United States.”

And in the modern protest era, more and more often environmentalists who might have once been narrowly focused or branched out from other movements are now in the middle of a far wider web of societal issues.

“The issue of policing in the United States, the militarization of police forces, Black Lives Matter, all those issues are bound up with protection of this forest for these activists,” Woodhouse said.

The conflict underlying “Cop City” has been simmering for about two years.

The police training center, proposed by the Atlanta Police Foundation and City of Atlanta, would sit on 85 acres that make up part of the 3,500-acre South River Forest, just southeast of the Atlanta city limits. The training center includes a “mock cityscape,” burn buildings, a kennel for police animals, a “vehicle operations course” and a firing range about half a mile from the nearest neighborhoods, according to the foundation.

Environmental groups lobbied against the construction of the training center, saying it would destroy tree canopy, harm habitat for amphibians and migratory birds, and make stormwater flooding more likely in surrounding areas. Some opponents see the training center as an exemplar of police militarization and have decried investments in policing.

The environmental movement is no stranger to radical tactics, civil disobedience and confrontation with authorities that sometimes result in arrests or violence.

During the 1980s, as radical environmentalists erected blockades, chained themselves to equipment and perched in treetops, “protesters were sometimes dragged away and thrown in vans, sometimes pepper-sprayed,” Woodhouse said.

But the escalation of violence in Atlanta reveals how the changing focus of the movement could be leading to more direct conflict with police.

Mike Roselle, a co-founder of the environmental advocacy group Earth First and a veteran environmental activist, said that even in some of the most combative days of forest activism, beginning in the 1980s, police were more often the third party to the confrontation.

“When you’re dealing with these logging protests, you want police on site because loggers would kill us,” said Roselle, who said he has been arrested about 50 times during a career of environmental protests. “We did have a little police violence against us, but it wasn’t a main issue.”

In Atlanta, as environmental protesters are pitted directly against the police department’s desire for a new training facility, they are making social justice concerns — like police brutality — part of the backbone of their movement.

Ebony Twilley Martin, co-executive director of Greenpeace USA, called the situation in Georgia “disturbing,” and said the police forest raids were “an attack on something that is essential to American democracy.”

“Environmental justice and racial justice are inextricably linked,” Martin said. “There’s no way that you can advance environmental justice without looking at the role that racism plays in that.”

As of Tuesday, Atlanta Police Chief Darin Schierbaum said he did not believe there were any demonstrators left in the forest. That same day, Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens and DeKalb County Executive Michael Thurmond announced that a permit had been issued to begin clearing land to move the training center project forward.