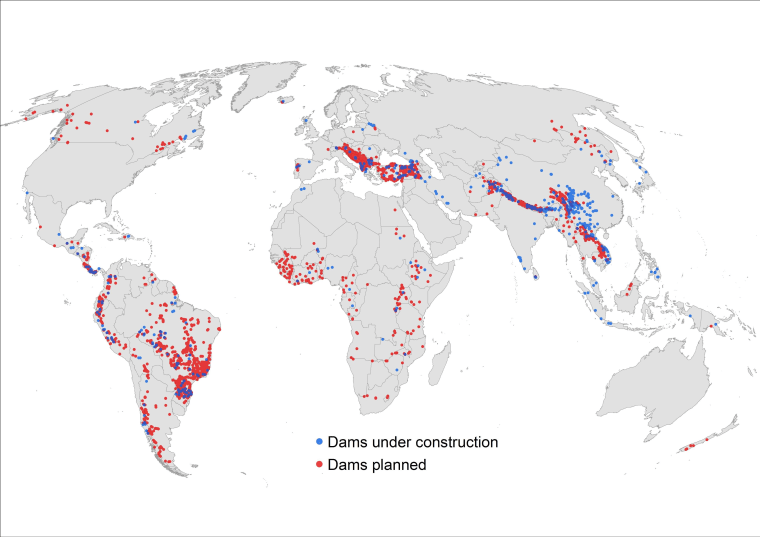

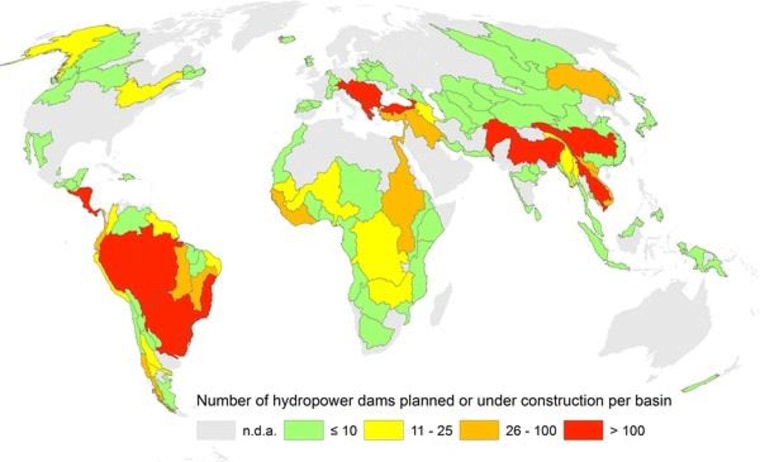

It’s an impressive number: 3,700 large hydroelectric dams being built or on the books, and the vast majority in developing countries. The unprecedented push promises jobs and electricity in destitute areas, but two new scientific studies warn that such dams, if not properly planned, could lead to a long-term bust for the communities and the wildlife around them.

A key challenge is that the boom is concentrated in areas of South America, Southeast Asia and Africa that are also bastions of relatively untouched freshwater ecosystems.

One study compiled a database of those dam projects, comparing how much energy they would produce to how many free-flowing rivers they would impact.

Global electricity supply would double if all were completed, the scientists calculated in the study, published in Aquatic Sciences, but electricity demand will also be rising significantly so hydropower's share of the global energy pie wouldn't change much.

In other words, "hydropower will not close the electricity gap," says lead author Christiane Zarfl, who conducted the study with colleagues at Germany's Leibniz-Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries.

Moreover, the team estimated that 25 of the 120 large river systems classified as free-flowing would lose that status, primarily in South America. "Worldwide, the number of remaining free-flowing large river systems will thus decrease by about 21 percent,” they wrote.

The second study, published Sunday in Nature Geoscience, found that sediment flowing down Amazon rivers is the key to creating the meanders that define the basin. Dams proposed along those rivers will block that sediment, reshaping the rivers into a more constrained basin, the researchers said.

"Certainly land owners may prefer a constrained river system where their property was protected from erosion, but the wider benefits of a dynamic river would be missed," lead author Jose Constantine, an earth sciences professor at Britain's Cardiff University, tells NBCNews.com.

"All of those dams will not only not solve our energy problems but invite more problems."

Those benefits, he says, include managing floods better, allowing fish to thrive and improving water quality by capturing runoff and pollution in what is essentially an ecosystem filter.

The boom has caught the attention of environmentalists, who worry about those last wild places. "What is even scarier is that all of those dams will not only not solve our energy problems but invite more problems in the form of floods and other natural disasters, and even conflict over water," says Rupak Thapaliya, national coordinator for the Hydropower Reform Coalition.

The sediment problem goes beyond constrained rivers to include shrinking deltas, says International Rivers spokeswoman Lori Pottinger, citing a 2009 study. "And that's when you start to see deltas sink, mangroves die, saltwater intrusion and, most importantly, the loss of natural protections against storms."

The industry says it has taken steps to minimize impacts, principally through a "sustainability assessment protocol" used by builders and created with help from The Nature Conservancy and WWF.

While the protocol doesn't specify guidelines or minimum standards, the International Hydropower Association calls it a "foundation step" that will lead to "follow-up work on different application and implementation pathways, all with the common objective of lifting sustainability performance in the hydropower sector."

"You can minimize the harm by changing the way you operate dams," acknowledges Thapaliya. "Some of the things you can do to mitigate a dam’s impacts are to release water into the river in the same manner as its natural flows, protect habitat for fisheries and other species, provide opportunities for migration of fisheries (e.g. by building fish passages), and preserving the water quality on the river."

In east Africa, Zarfl's team noted as an example, fragmentation impacts could be reduced by abandoning hydropower dam projects in the Rufiji River, the region's last remaining large free-flowing river, while boosting capacity on the Nile and Zambezi rivers, which are already heavily fragmented.

Dam planners could also look to the U.S. for lessons. The areas ideal for large dams were tapped decades ago, which explains why no new large dams are planned in the continental U.S., and that legacy provides examples of pitfalls but also promises.

One such lesson is along California's Sacramento River, notes Constantine, where a stretch was rechanneled to better mimic natural river processes.

But International Rivers, which has its own interactive map of dam projects, doesn't see much effort from dam builders like China and financial backers like the World Bank.

"They're not learning from their past mistakes," says Pottinger, noting that the sustainability protocol is based on assessments that are not binding.

She also notes that a "gold standard" for construction guidelines that was prepared by the World Commission on Dams, and which the World Bank sponsored, was never widely implemented.

Pottinger does think the boom eventually will be constrained by global warming since dryer climates mean less river flow and less electricity. "So one way or the other the problem will take care of itself," she believes.

Zarfl's team hopes that its database can be used by planners to better site and build dams, but that's a big task given the hundreds of large dams on the way in remote corners of the planet.

"The biggest issue in river management," says Constantine, "is that satisfying short-term needs doesn’t always support the long-terms needs of the river system."