Across the globe, reef-building corals live in symbiosis with algae, which provide the animals with food and their iconic brilliant color. But environmental stress — high temperatures, in particular — can kill corals by causing them to "bleach," a process in which they lose their vital algal friends and turn ghostly white.

Scientists have long thought that faulty algal photosynthesis (the process that uses light to make food) ultimately triggers coral bleaching, but new research now shows that substantial bleaching can also occur when heat-stressed corals are not exposed to light (such as at night).

The study, published Thursday in the journal Current Biology, suggests that different molecular mechanisms may spark coral bleaching and that certain strategies proposed to prevent bleaching, such as shielding corals from sunlight when water temperatures are high, may need to be re-evaluated.

"The results make us rethink how coral remediation might be achieved," said study lead author Arthur Grossman, an algal physiologist at the Carnegie Institution for Science in California. "As we learn more about the mechanisms involved in coral bleaching, we may be able to ameliorate the situation a bit more." [In Images: A Trip to the Coral Triangle]

Coral reefs in danger

Coral reefs are sometimes called "rain forests of the ocean," as they are an important part of the aquatic ecosystem, providing food and shelter for countless marine species. But coral reefs around the world are in decline due to a number of different issues, including overfishing, water pollution and coastal development.

A greater problem, however, may be atmospheric carbon dioxide. Since the industrial revolution, humans have increasingly piped more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, much of which the ocean then absorbs. The resulting chemical reactions reduce seawater pH, making it more acidic. "If the water gets more acidic, it's harder for corals to make calcium carbonate for their skeletons," Grossman told LiveScience. Ocean acidification slows coral growth and weakens the reef infrastructure, making it more vulnerable to erosion and predators.

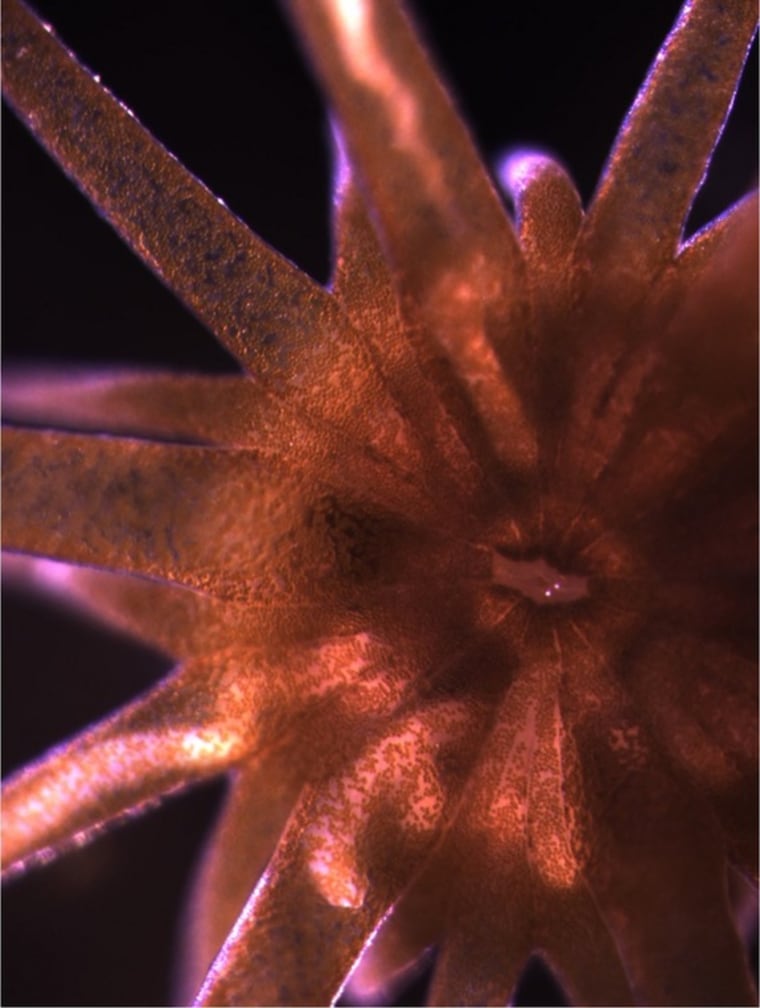

Increased atmospheric carbon dioxide also raises global temperatures, which leads to coral bleaching — the breakdown of the symbiotic relationship between coral polyps and single-celled algae called zooxanthellae. Normally, algae supply corals with oxygen, glucose, glycerol, amino acids and other nutrients, while corals protect algae and feed them the compounds they need for photosynthesis.

Until now, the prevailing theory behind coral bleaching explained that when water temperatures are too high, the photosynthetic apparatus of algae — the chloroplast — is unable to efficiently process incoming light. The algae begin producing toxic, reactive oxygen molecules during photosynthesis, which interact with and disrupt algal membranes and proteins. The excess oxygen can also react with the water to produce hydrogen peroxide, which damages coral tissue.

After a while, the algae separate from the corals, though scientists aren't sure if the corals expel the algae or if the algae abandon the corals. Without the algae, the corals become bleached and will die if they don't quickly take up zooxanthellae again.

Heat-stressed algae

Grossman and his colleagues wondered if coral bleaching can still occur if algae are heat-stressed and in the dark, when the photosynthetic machinery is turned off. To find out, they first tested how a model system — the sea anemone, Aiptasia, and its algal symbiont, Symbiodinium — responds to heat stress.

They found that the sea anemone loses its algae in both the light and dark at 93.2 degrees Fahrenheit (34 degrees Celsius), and that the heat damages the algae's photosynthetic abilities; that is, they saw that the remaining algae fluoresce less than normal (fluorescence has previously been indicated as a way to test the health of coral). When the team returned the sea anemones to their normal temperature of 80.6 degrees F (27 degrees C), the animals continued to bleach for several days, but their algal populations eventually returned to their pre-stress levels.

The researchers then heated up nine reef-building corals from the genus Acropora, which came from Ofu Island in American Samoa and from the Monterey Bay Aquarium in California. At 93.2 degrees F, seven of the coral species bleached (the team isn't sure if the two other species would have bleached under higher temperatures). [Images: Colorful Corals of the Great Barrier Reef]

"The surprising thing is that in many cases, the bleaching was just as strong in the dark as it was in the light," Grossman said. "Photosynthesis is not necessary for bleaching to occur, though it may exacerbate bleaching."

A lingering mystery

The researchers suggest that other mechanisms may also trigger coral bleaching, such as nitric oxide molecules released during heat stress or reactive oxygen molecules that don't come from photosynthesis.

Another possibility is that the heat disrupts the functions of the algae and coral membranes, which allow the symbionts to pass nutrients between each other. In this case, the coral or algae realize they are not getting what they need, so they separate. There is some validity to this idea, Grossman said — in another experiment, the team discovered that they could get sea anemones to spit out their algae if they stopped photosynthesis with a drug.

Grossman also notes that the research shows that corals change color during bleaching because of the loss of algae. Some scientists have previously suggested that corals may turn white because the algae lose their pigmentation, but Grossman and his colleagues found that the expelled algae were still pigmented.

The researchers think that ejecting the algae in the dark during heat-stress may actually be beneficial to the coral. "When the light comes up the following day, if you still have algae in there you will get more reactive oxygen species and eventually destroy yourself," Grossman explained, adding that future work will tease out any advantages there may be to coral bleaching and elucidate the role that gene expression plays in the matter.

"We want to continue probing it on the molecular level and trying to pinpoint those specific mechanisms that will let us understand this whole process," Grossman said. "Then maybe we can do something about coral bleaching."

Follow Joseph Castro on Twitter. Follow us @livescience, Facebook and Google+. Original article on LiveScience.