The most severe extinction in the earth's history began 252 million years ago, wiping out 90 percent of ocean species and 70 percent of life on land. Modern sharks and their relatives were among the few that survived this "Great Dying," and new fossil finds hint as to how they may have clung on to life.

A paleontological dig site in southern France, containing sediment from a much younger Cretaceous ocean floor, now have yielded fossilized teeth of a tiny shark relative, indicating that the fish found refuge by swimming to deeper oceans.

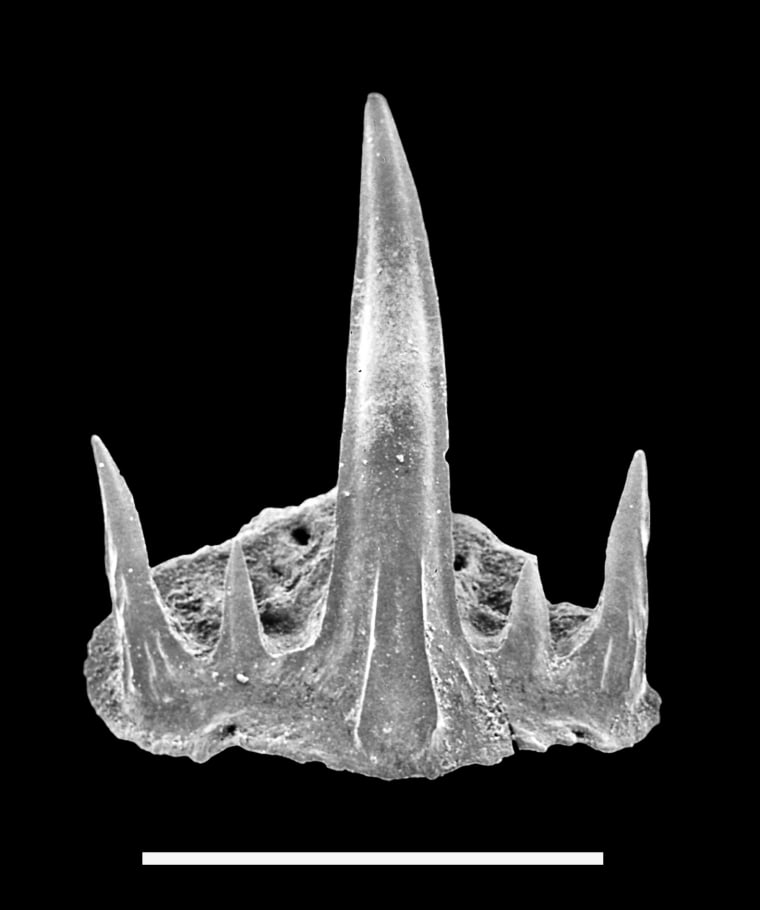

The collection of millimeter-long teeth belong to three species of cladodontomorph sharks — not massive fish like we know them to be, but tiny, inch-long swimmers — relatives of modern sharks, skates and rays. They thrived in the Permian ocean prior to the extinction and researchers had thought they had perished in the Great Dying — until they were found in soil that was 135 million years fresh.

The tiny sharks, fleeing the acidic coastal waters of the end-Permian, moved to deeper oceans, and lived there for a hundred million years, Guillaume Guinot, a researcher at the Natural History Museum in Geneva, Switzerland, and his colleagues explain in the Tuesday issue of Nature Communications.

"It changes our view of how dramatic this extinction event was," Guinot told NBC News. The find suggests that there may be many more fishes living in deep ocean sediment deposits that haven’t been found yet, and that may indicate that the "extinction wasn’t that dramatic for cartilaginous fishes."

The new findings also allow for the possibility that modern sharks survived the die off in a similar way, by moving to deep open ocean that was perhaps less changed. "These are just ideas," he clarified, because there is no hard, ossified evidence that modern sharks also swam to deeper oceans and died (and fossilized) there.

More about shark origins:

- Ancient ocean predators were reptiles that swam like sharks

- Stunning tail: Thresher sharks evolved to slap and kill their prey

- Sharks dominated prehistoric seas off France, UK

In addition to Guillaume Guinot, the authors of "Cretaceous stem chondrichthyans survived the end-Permian mass extinction" include Sylvain Adnet, Lionel Cavin and Henri Cappetta.

Nidhi Subbaraman writes about science and technology. You can follow her on Facebook, Twitter and Google+.