It's plausible that conditions on Earth could get so hot and steamy that the oceans entirely evaporate and render the planet inhospitable to life, according to new calculations that suggest this so-called runaway greenhouse is easier to initiate than previously believed.

"We could go into the runaway greenhouse today if we could get the planet hot enough to get enough water vapor into the atmosphere," Colin Goldblatt, a professor of Earth system evolution at the University of Victoria in British Columbia, Canada, and lead author of the study, told NBC News.

The reality, though, he said, is that burning all the planet's fossil fuels such as oil and coal is "very unlikely" to trigger the uncontrollable warming.

"Our estimate is that it would take 30,000 parts per million of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere to make it warm enough to trigger this runaway greenhouse," Goldblatt said.

Today, the carbon dioxide level is 400 parts per million, a milestone crossed this May for the first time in several million years. Burning all the planet's fossil fuels such as coal and oil would lead to 2,000 to 3,000 parts per million, a factor of ten difference.

Getting to 30,000 parts per million "really seems quite unlikely," Goldblatt said. The outlier chance of a runaway greenhouse due to human activity, he noted, stems from the inherent uncertainty in the calculations.

The uncertainty led the researcher and his colleagues to conclude in a paper published Sunday in Nature Geoscience that "anthropogenic emissions are probably insufficient" to trigger a runaway greenhouse.

The calculations "are significant" and "done by a very capable team," David Grinspoon, the curator of astrobiology at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, told NBC News in an email.

"I find their conclusion that the danger of humans triggering a runaway is remote to be both sound and vaguely reassuring," he added. "However, this work also reminds me of how much more we need to do to really understand long-term climate change and that makes me uncomfortable."

Calculating a runawaygreenhouse

The runaway greenhouse becomes possible when the Earth absorbs more energy from the sun than can escape to space, putting the planet out of thermal balance.

Think of the atmosphere as akin to a bathtub with the plug pulled out, allowing a certain amount of water to swirl down the drain, Goldblatt said.

"If you turn the taps on harder, you will fill it up with more water than can get out at one any one time, then eventually your bath is going to fill up to overflowing," he explained. "And it is the same kind of process with the runaway greenhouse."

The greenhouse effect stems from the fact that water vapor, carbon dioxide, and other gases in the atmosphere absorb some of the energy radiated from the Earth. Only a fixed amount can escape from the atmosphere to space.

"If we absorb more solar radiation than that maximum we can emit, then all that can happen is the Earth is going to warm," Goldblatt said. "It just can't keep itself in energy balance anymore."

He and colleagues used modern computing power and models of the behavior of greenhouse gases to revisit the classic calculations of the conditions necessary for a runaway greenhouse on Earth, which were originally done in the 1980s.

They found that the maximum amount of solar radiation that can escape to the atmosphere is lower than previously thought and it is easier than thought for a steamy atmosphere to absorb sunlight.

In other words, it is easier to trigger the runaway greenhouse than believed and this is all possible on a planet that receives the same amount of solar radiation as the Earth does today, he said.

Finding Goldilocks

Rather than raise alarm about human-caused climate change, Goldblatt said, the study illustrates the variety of plausible climate states Earth could be in and hammers home the benefit of Earth being in the so-called Goldilocks zone for life — not too hot, not too cold.

The new study also illustrates how difficult it is to determine habitability of planets around other stars, "because it will depend on the detailed history of planets, not just their distance from a star," Grinspoon, the astrobiologist, said.

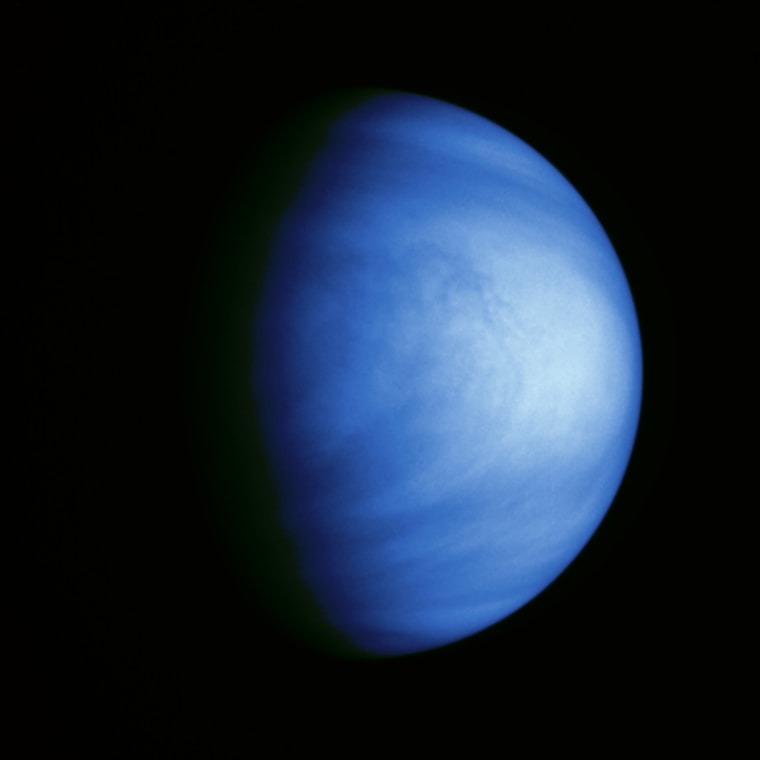

"This makes me realize that we really need to explore our closest neighboring planet, our sister Earth, Venus," he added.

Venus is thought to have been victim of a runaway greenhouse, which boiled off its oceans. And as the sun's solar radiation continues to intensify in the future, the Earth too will be similarly cooked.

"Venus shows us what we will be like in the future," Goldblatt said, "and it is not pretty."

John Roach is a contributing writer for NBC News. To learn more about him, visit his website.