Thousands of monumental structures built from walls of rock in Saudi Arabia are older than Egypt's pyramids and the ancient stone circles of Britain, researchers say – making them perhaps the earliest ritual landscape ever identified.

A study published Thursday in the journal Antiquity shows that the mysterious structures dotted around the desert in northwestern Saudi Arabia – called "mustatils" from the Arabic word for "rectangle" – are about 7,000 years old. That’s much older than expected, and about 2,000 years older than either Stonehenge in England or the oldest Egyptian pyramid.

“We think of them as a monumental landscape,” said Melissa Kennedy, an archaeologist at the University of Western Australia in Perth and an author of the study. “We are talking about over 1,000 mustatils. These things are found over 200,000 square kilometers [77,000 square miles], and they’re all very similar in shape ... so perhaps it’s the same ritual belief or understanding.”

“There must have been a great level of communication over a very big area, because how they were constructed was communicated to people,” lead author Hugh Thomas, an archaeologist at the same university, said.

The research is funded by the Royal Commission for AlUla, which has been established by the government of Saudi Arabia to preserve the heritage of the AlUla region in the northwest of the country, where many mustatils are found.

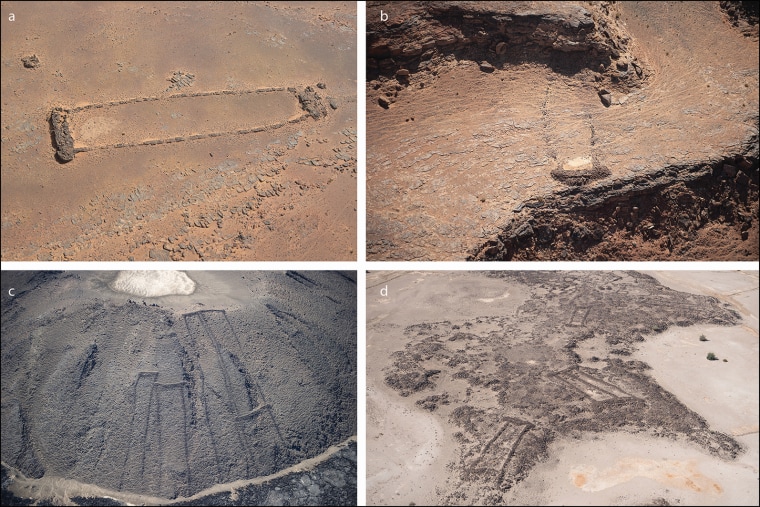

Some of the ancient structures are more than 1,500 feet long, but comparatively narrow, and they’re often clustered together. They’re usually built on bedrock, often on rocky outcrops above the desert, but also in mountains and in relatively low-lying areas.

The simplest mustatils were made by piling up rocks into low walls a few feet high to form long rectangles, with a thicker “head” wall at the highest end and a narrow entranceway on the opposite side. The researchers think they may have been built to guide a procession from one end to the other. But they also found many mustatils that were much more complex than they first thought, containing pillars, standing stones and smaller "cells” of rock walls. Kennedy and Thomas estimate one mustatil they surveyed was built by moving more than 12,000 tons of basalt stone – an arduous task that must have taken dozens of people months to complete.

It’s not known just why the ancient peoples who built the mustatils made so many. Kennedy speculates that some may have been used only once, or that different mustatils near each other were made and used by different groups of people.

One clue to their purpose is that the head walls of many mustatils have a small chamber or niche that seems to have been used for sacrificial animal offerings. Excavations in 2019 of the chamber of one mustatil found the horns and bones of wild and domesticated animals, including sheep and gazelles, but mostly cattle. The bones allowed the researchers to fix the date of the offerings to about 5,000 B.C., during the late Neolithic period when the region was much wetter and greener than the arid landscape today.

Ancient rock drawings show herds of cattle that must have been integral to the subsistence of the Neolithic people in the region, and Kennedy and Thomas suspect the mustatils were part of an ancient “cattle cult” that celebrated the animals. Archaeological evidence has been found of a cattle cult in the south of Arabia about 900 years later, Kennedy said, and the mustatils may have been an early expression of that belief; it may also be that some mustatils were built to establish territorial claims on valuable pasturage for herds.

“This is one of the most important archaeological papers in recent decades,” said archaeologist Huw Groucutt of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History at Jena in Germany, who has studied mustatils on the southern margins of the Nefud Desert but who was not involved in the AlUla research. “Most research is just about adding a few details to things that are already known. The mustatil phenomenon is something really new.”

He notes that the northwest of Saudi Arabia where most mustails are found has traditionally been neglected in studies of prehistory.

“These thousands of mustatils really show the creation of a monumental landscape,” he said in an email. “They show that this part of the world is far from the eternal empty desert that people often imagine, but rather somewhere that remarkable human cultural developments have taken place.”