On Monday, the White House coronavirus response coordinator warned that the U.S. could see up to 200,000 deaths from the outbreak "if we do things almost perfectly."

On Tuesday, the coordinator, Dr. Deborah Birx, showed how her team came up with the grim projection.

In a task force briefing, the White House offered the first look at the statistical models being used to anticipate how the virus could spread across the U.S. and what drove President Donald Trump to extend his administration's nationwide social distancing guidelines until April 30.

Full coverage of the coronavirus outbreak

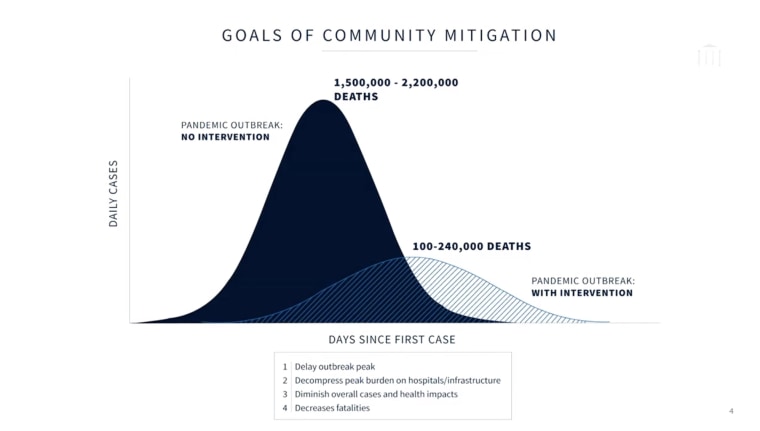

Epidemiologists, who study the spread of infectious diseases, rely on data collected about diseases combined with statistical analysis to create predictive models of different outcomes to figure out how best to deal with outbreaks. A model developed by researchers at Imperial College London and published March 17 suggested that without any mitigation measures in place, the coronavirus could kill 2.2 million people in the U.S.

That's an entirely hypothetical scenario, because it assumes that all government agencies would ignore the virus and would take no steps, such as social isolation, to reduce its spread. Nonetheless, the stark findings were reported to have been among the first to prompt U.S. authorities to take drastic action.

According to Birx, the latest figures from the White House came from combining the Imperial College London model with a half-dozen other models from leading epidemiology teams around the world.

The projections unveiled Tuesday suggest that the pandemic could kill 100,000 to 240,000 people in the U.S. by mid-June, even with strict mitigation measures in place over the next 30 days.

Trump called the estimated death toll "sobering." He said the weeks ahead will be challenging as new cases multiply and deaths mount.

"I want every American to be prepared for the tough days ahead," Trump said Tuesday during the White House's coronavirus task force briefing. "This is going to be a very, very painful two weeks."

Birx presented data on how the virus could spread across the U.S. over the coming weeks and months. The estimates were based on the outbreak's trajectory in Italy — which has reported more than 101,000 confirmed cases and more than 11,500 deaths — and virus hot spots, such as New York and New Jersey, that have already developed in the U.S.

Epidemiological models are not set in stone. They offer a variety of outcomes depending on what action is taken, best illustrated in the differing shapes on many "flatten the curve" graphs, with one steep mountain showing what happens if no action is taken and another gentle, long hill showing what happens if steps like social distancing are widely embraced.

Models have shown that early action and extreme social distancing measures in Washington state and California are having noticeable impacts, according to Birx. Although both states had clusters of coronavirus cases in late February, shelter-in-place policies and other mitigation techniques have helped keep the rates of infection relatively low, she said.

If other states can maintain similar measures, it may be possible to avoid the surge in new cases and deaths that is being seen in New York, New Jersey and parts of Louisiana.

"That's the piece that we're trying to prevent in New Orleans, in Detroit, in Chicago and Boston right now," Birx said.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said the projection of 100,000 to 240,000 deaths is grim, but he stressed that adhering to the social distancing guidelines can push the numbers down and that models will be adjusted continuously as data become available.

"We need to anticipate, but that doesn't mean it's what we're going to accept," he said.

One of the best-known forecasts comes from researchers at the University of Washington's Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Their projections anticipate a steep rise in the death toll in April before the number of daily deaths slows. But the study diverges from the White House's anticipated death toll, with the University of Washington predicting that nearly 84,000 people could die by early August.

Part of the reason projections tend to vary is that they inherently rely on assumptions. They might assume, for example, that everyone in each state will follow social distancing orders.

"The models are as good as the assumptions, and this is a brand new virus, so locking down the assumptions is really the hard part," said Dr. Peter Jay Hotez, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston and co-director of the Texas Children's Hospital Center for Vaccine Development.

Download the NBC News app for full coverage and alerts about the coronavirus outbreak

Other factors that aren't incorporated into existing models include the potential seasonality of the virus or whether there will be new and subsequent waves of infections. Some infectious diseases, including other known coronaviruses, emerge on seasonal cycles, but it's not yet known whether the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 will do the same.

"Whether this comes back in the fall or next year around this time is anybody's guess," Hotez said. "Sometimes we get surprised — like with Zika virus, it peaks in 2016 and then abruptly tailed off in 2017, and we haven't seen it since. I'm not sure we really understand why."

Still, some researchers saw glimmers of hope in the stark projections, particularly because communities have the opportunity to change the outcome by being vigilant about social distancing. However, the measures can be challenging to enforce, because the outcomes are not immediately apparent, said Efraín E. Rivera Serrano, a research associate in virology and cell biology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

"It's not immediate gratification, which we humans tend to like," he said. "It's a method where things aren't just going to stop right now, and we won't have answers immediately. I don't want people to get discouraged by the numbers."

Keeping up the momentum will be especially important, as it may take longer than 30 days to slow the spread of the virus, said Hotez, who said nationwide social distancing measures may need to be kept up beyond April 30.

"I'm looking at that April 30 date as a benchmark to see where we're at in this epidemic," he said. "I'm not considering that a true date to stop. It'll probably be a date to reflect, and then we'll have to make a go/no go decision on whether to extend this for an additional month or so."