Readings from the Hubble Space Telescope have revealed the extent of a massive, nearly invisible halo of gas surrounding the neighboring Andromeda Galaxy — and it's a doozy. The dark halo stretches out about a million light-years beyond the spiral galaxy's stars, which is roughly half the distance to our own Milky Way.

Thus, if our own Milky Way has a similar halo — and there's no reason to think it doesn't — the stuff from the two sister galaxies could already be mixing together.

If you could see Andromeda's halo with your naked eye, it would span 100 times the diameter of the full moon in the night sky, the Hubble team said in Thursday's image advisory. But you can't see it. That's the challenge.

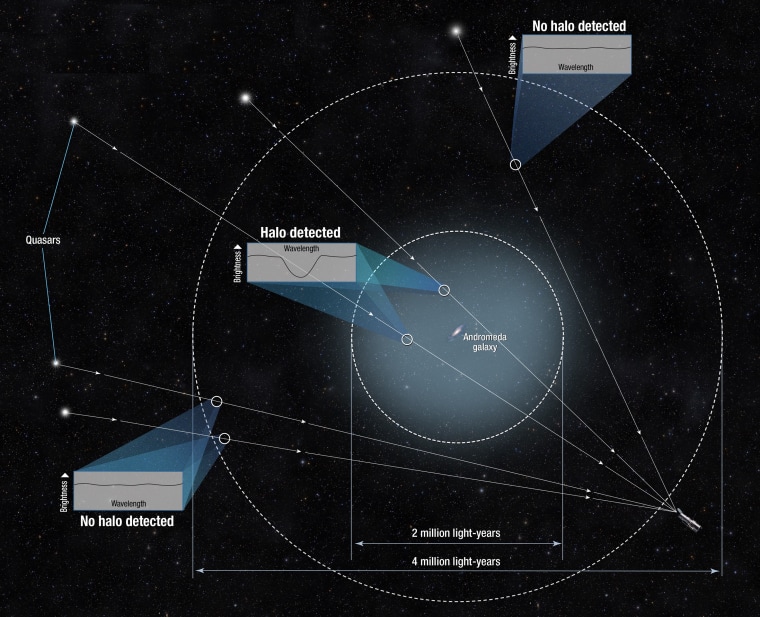

An earlier Hubble survey known as COS-Halos detected gaseous halos around more distant galaxies, but the newly published research used observations of 18 faraway quasars in ultraviolet light to map the halo around Andromeda, also known as M31, in unprecedented detail.

See a Full-Size Version of the Halo Infographic

"As the light from the quasars travels toward Hubble, the halo's gas will absorb some of that light and make the quasar appear a little darker in just a very small wavelength range," Notre Dame astronomer J. Christopher Howk explained in the advisory. "By measuring the dip in brightness in that range, we can tell how much halo gas from M31 there is between us and that quasar."

The project's lead investigator, Notre Dame's Nicolas Lehner, told NBC News that the observations confirmed a prediction that the gaseous halos around galaxies should extend out to their gravitational sphere of influence.

"Previous observations had only one target beyond each galaxy, and with a large sample of galaxies, they could infer that the gas could extend quite far from the galaxies," Lehner said in an email. "However, these galaxies have different masses and stellar activities. Our observations show for the first time for a single galaxy that it has a massive halo as predicted by galaxy models."

In a study published in the May 10 issue of The Astrophysical Journal, Lehner and his colleagues say the halo of hydrogen and helium gas probably formed at the same time as the rest of the galaxy. Since then, it's been enriched with heavier elements that were created by exploding stars called supernovae. The researchers say nearly half of all the heavy elements made by Andromeda's stars have been expelled beyond the galaxy's 200,000-light-year-wide stellar disk.

The nearly invisible halo has half as much mass as all the stars in Andromeda combined, and perhaps more — so could such halos account for the mysterious dark matter that astronomers have been puzzling over? Not even close, Lehner said.

"It's a very massive halo, but it's still less than a tenth the mass of the dark matter," he told NBC News.

Lehner, Howk and Bart Wakker are authors of the paper titled "Evidence for a Massive, Extended Circumgalactic Medium Arouind the Andromeda Galaxy."