In the race to land the first humans on Mars, NASA is betting big on nuclear rocket engines to get its astronauts to the red planet.

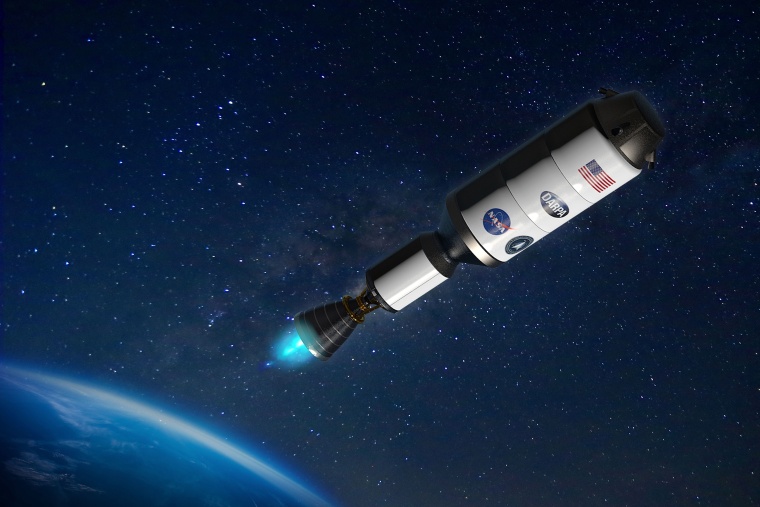

Earlier this year, the agency announced a partnership with the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA, to develop a rocket that uses nuclear propulsion to carry astronaut crews to deep-space destinations like Mars. This type of technology would significantly cut down on the time needed to reach Mars, making long-duration spaceflights less risky for the humans onboard.

A conventional spacecraft powered by burning liquid fuel typically takes around seven or eight months to reach the red planet. Scientists have said nuclear rocket engines could shave off at least a third of that time.

NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said the shortened journey would give crews more flexibility on missions to Mars.

“You enable yourself to be on the surface for maybe three weeks, four weeks, and get back within a reasonable amount of time, instead of having to be gone for two or three years,” he said.

A shorter round trip also means the astronauts would be exposed to less cosmic radiation while in space. Studies have shown that without the protection of Earth’s atmosphere and magnetic field, humans can receive the equivalent of an entire year of radiation on Earth in just one day in space. For missions to Mars, that means an astronaut could be exposed to radiation levels 700 times higher than on Earth, according to the European Space Agency.

To reduce these risks, DARPA — the branch of the Defense Department responsible for experimenting with new and emerging technologies — is developing a rocket powered by nuclear thermal propulsion. The program has been dubbed DRACO, short for Demonstration Rocket for Agile Cislunar Operations.

The system uses high heat from a fission reactor to turn liquid propellant into a gas, which is then funneled through a nozzle to power the spacecraft.

This type of propulsion can create more thrust and is at least three times as efficient as chemical rockets, according to NASA. That means needing to carry less fuel onboard, which frees up room to haul more equipment, science experiments or other cargo to the Martian surface.

“It can completely change the game of how people think about what is possible in space — what you can carry, how quickly you can get there,” DARPA Director Stefanie Tompkins said. “You have much more flexibility in getting where you want, when you want.”

And though the system runs on nuclear power, Nelson said it would use low-enriched uranium rather than weapons-grade, highly enriched uranium.

“This is safe nuclear technology,” he said.

He added that tests of the nuclear rocket engine would not occur on Earth and would instead take place in space, with safety being the highest priority. The first DRACO demonstration could happen as early as 2027, according to NASA.

Daniel Dumbacher, executive director of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, called nuclear propulsion a major step forward for space exploration.

Missions to Mars naturally include myriad risks to human health, he said, but nuclear technology could limit some of the consequences, including the psychological toll on crews confined within cramped quarters.

“There’s the psychological aspect of being away from home for that long,” Dumbacher said. “How does the human mind deal with being in something the size of a school bus for months and months? How do we keep the mind entertained? How do we keep morale up? All of these challenges grow exponentially when you go out to Mars, so shortening the trip time is a big, big deal.”

The blueprints for a nuclear rocket engine were initially drawn up in the 1960s. But the program stalled after the Three Mile Island accident in 1979 and the Chernobyl disaster in 1986 turned public opinion against nuclear technology.

Now, Nelson said there’s more appetite and political will to explore alternative fuels.

Tompkins said the promise of nuclear propulsion was there in the 1960s, but the program was never able to reach its full potential. She said this current environment is the “right time” in history to evolve the technology to the next level.

“When I go back and I read the reports from those days,” she said, “I am continually reminded that we all get to stand on the shoulders of giants.”