The world is hurtling toward a stark future where the web of life unravels, human cultures are uprooted, and millions of species go extinct, according to a new study. This doomsday scenario isn't far off, either: It may start within a decade in parts of Indonesia, and begin playing out over most of the world — including cities across the United States — by mid-century.

What's more, even a serious effort to stabilize spiraling greenhouse gas emissions will only stave off these changes until around 2069, notes the study from the University of Hawaii, Manoa, published online Wednesday in the journal Nature. The authors warn that the time is now to prepare for a world where even the coldest of years will be warmer than the hottest years of the past century and a half.

"We are used to the climate that we live in. With this climate change, what is going to happen is we're going to be moving outside this comfort zone," biologist Camilo Mora, the study's lead author, told NBC News. "It is going to be uncomfortable for us as humans and it will be very uncomfortable for species as well."

Pivot in perspective

The research represents a pivot in the way climate scientists study and parse the pace, magnitude and implications of a warming world, according to experts not involved with the new study. Its focus on climate variability rather than absolute change, for example, shifts attention from the remote Arctic and its polar bears stranded on ice floes to the tropics, where most of humanity resides.

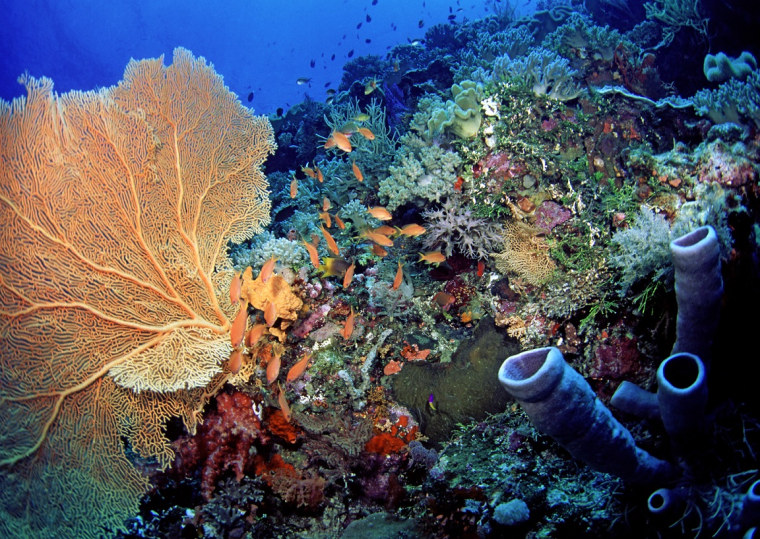

Yes, the climate is warming rapidly in the Arctic and the effects are profound. But climate variability in the northern latitudes is much greater than in the tropics. In the already steamy parts of the globe, warming of even a few degrees can upset the balance of life and cripple agricultural yields, bringing climate change to the doorstep of billions of people.

"The warming in the tropics is not as much but we are rather more quickly going to go outside that recent experience of temperature and that is going to be devastating to species and it is probably going to be devastating to people," Stuart Pimm, a conservation biologist at Duke University, who was not involved with the new study but is familiar with its contents, told NBC News.

Indexing the future

Mora and colleagues from the University of Hawaii used a collection of global climate models to create an index of estimates on when a given spot on the globe is likely to change beyond the norms of variability between 1860 and 2005.

"On average, the tropics will experience unprecedented climate change 16 years earlier than the rest of the world, starting as early as 2020" in Manokwari, Indonesia, Mora said in a briefing with reporters on Tuesday.

Under a business-as-usual scenario where humans keep burning fossil fuels as they are today, globally that threshold is crossed around 2047. Santo Domingo in the Dominican Republic crosses it in 2026, Paris in 2054, and Austin, Texas, in 2058, for example. If greenhouse gas emissions are stabilized, these dates are delayed only by several decades.

The numbers are subject to geographic variability, which is why the paper expresses the global average under the business-as-usual scenario as between 2033 and 2061. In other words, the changes are not taking place at the same time all over the world. But for any given location, the uncertainty of when departure occurs is five years on either side of the date given. Mora called this narrow uncertainty "remarkable" given that the study included 39 different models from 21 teams in 12 countries.

Skeptics are likely to focus on the precision of these numbers and how they were derived, Eric Post, a biologist at Penn State University, noted in an accompanying commentary in Nature, but added that the methodology may advance understanding of the role of climate change in biodiversity loss, especially at the regional level.

"If the assessment by Mora et al. proves accurate, conservation practitioners take heed — the climate change race is not only on, it is fixed, with the extinction finish line looming closest for the tropics," he wrote.

Future choices

According to Mora's team, the pending shift to a new climate regime presents all species in any given region three choices: move to a more suitable climate or stay put and adapt. If neither of those is possible, the third choice is extinction. And for many species in the tropics that are adapted to a stable climate, migrating to the more variable climates of higher latitudes isn't an option, Pimm noted.

The same may be said for humans, Mora told NBC News. "We have these political boundaries that we cannot cross as easily. Like people in Mexico — if the climate was to go crazy there, it is not like they can move to the United States."

Depending on the mitigation scenario, by 2050 between 1 and 5 billion people will live in areas with unprecedented climate, study co-author Ryan Longman, a graduate student at the University of Hawaii, said in the call with reporters.

"Countries first impacted by unprecedented climate change are the ones with the least economic capacity to respond. Ironically, these are the countries that are least responsible for climate change in the first place," he said. "By expanding our understanding of climate change, our paper reveals new consequences for biodiversity and highlights the urgency to take action now."

But trying to compel action with a stark warning about a future that is coming regardless of what efforts are taken to curb greenhouse gas emissions may be misguided, according to Roger Pielke Jr., a climate policy analyst at the University of Colorado at Boulder.

"It is better to design policies that have short-term benefits" such as jobs, energy access or less pollution "which can also address the longer-term challenge of accumulating (carbon dioxide) in the atmosphere," he said. "That is a policy-design problem that we have yet to figure out, and which does not involve trying to scare the public into action."

John Roach is a contributing writer for NBC News. To learn more about him, visit his website.