The season finale of HBO's "Game of Thrones" delivered plenty of shockers, but one of the most visually shocking scenes was the public shaming of Queen Cersei, a character who was forced to confess to adultery — and made to walk naked through the streets of the capital city as punishment.

Because this is HBO, the nudity is full-frontal, and full-backal, too — but not at all sexy. Spittle and offal can be such a turn-off.

It's the sort of humiliation that harks back to medieval times, when adulterers were forced to walk naked through their villages, and were left vulnerable to beatings along the way. Less radical forms of public shaming are used as punishments to this day. The issue has even come up in Jeb Bush's presidential campaign, with regard to unwed mothers.

But does public shaming work? Would it cause Cersei to behave herself on "Game of Thrones"? The evidence for that is murky at best in real life — and the available research suggests that Cersei is the wrong kind of offender to punish with a walk of shame.

A medieval model

Like so many of the twists in the TV show, and in the novels by George R.R. Martin on which the show is based, Cersei's shaming is based on medieval lore. Martin drew the inspiration for the Stark-vs.-Lannister family rivalry from the York-vs.-Lancaster battles in England's Wars of the Roses. Cersei's story parallels the saga of Jane Shore, a mistress of King Edward IV who was forced to take a walk of shame after Richard III took the throne in 1483.

Shore was targeted as much for her behind-the-scenes political maneuverings as for her adultery, said Larissa Tracy, who is an expert on medieval literature at Longwood University as well as a "Game of Thrones" fan. After her public humiliation, Shore was thrown into prison — but eventually she got out and married the king's solicitor general.

"After that, she more or less stayed out of the politics of the realm," Tracy, the author of "Torture and Brutality in Medieval Literature," told NBC News.

That's not likely to happen with Cersei, who will be itching for revenge next season. "For Cersei, I think it's just the start," Tracy said.

How shame has evolved

In the medieval era, public shaming signified that a person accused of wrongdoing had lost his or her "fama," or good standing in society. As such, the person was left open to further indignities, because the justice system was weighted against those with lower standing, Tracy said. She delves more deeply into the parallels between "Game of Thrones" and medieval literature — including the Arthurian tales of Queen Guinevere's travails — in an essay on Longwood University's website.

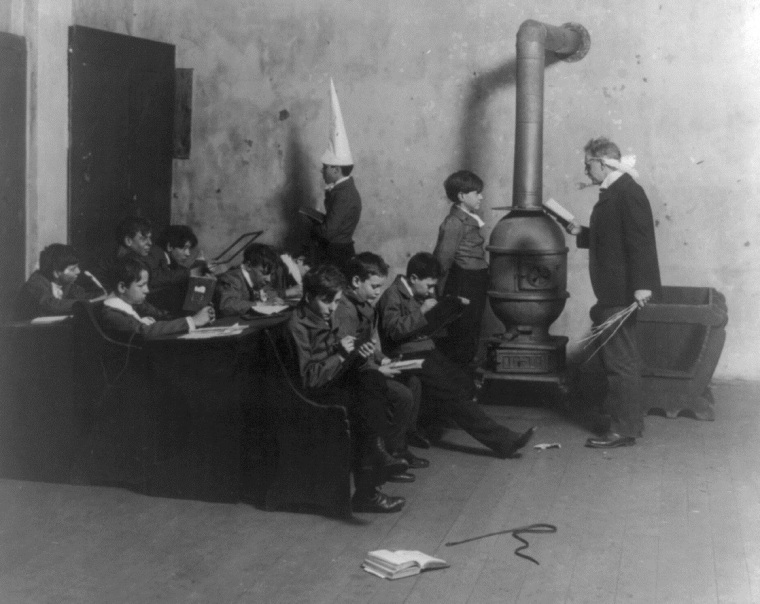

Shaming was a prominent part of the punishment process well after medieval times, said Peter Stearns, a historian at George Mason University. The best-known example comes from American fiction in the form of "The Scarlet Letter," penned by Nathaniel Hawthorne in 1850. But the history books are also replete with accounts of criminals being locked in stocks or pillories for public humiliation, and of kids being forced to wear dunce caps in school.

By the end of the 19th century, stocks were banned as an instrument of punishment throughout the United States. Public shaming has also fallen out of favor as a childrearing strategy, at least in Western societies. "There's still lots of humiliation in schools, but there are no codified practices," Stearns told NBC News.

Several reasons have been proposed for the decline of shaming: One is that modern Western communities are less cohesive than they were in past centuries — which dilutes the impact of humiliation.

That's not to say that the shame game has ended.

"The complexity is that over the past couple of decades, public shaming has made something of a comeback," Stearns said. For example, some defendants have been sentenced to hold up signs in public saying "I Stole Mail," or "I Am a Thief," or "I Stole From a 9-Year-Old on Her Birthday."

Meanwhile, social media networks have provided new avenues for public shaming. Stearns pointed to the case of Nobel-winning biochemist Tim Hunt, who was pilloried last week for sexist remarks about "the trouble with women" in science labs. "This guy was shamed and degraded in two days," Stearns said.

Does shame work?

Amid all the ups and downs in public shaming, experts say there's been precious little research into the efficacy of the technique. One of the standout studies was conducted by a team led by psychologist June Tangney, a colleague of Stearns' at George Mason University.

"Although shame is effective for punishing people, it's not clear that it helps them avoid doing harm in the future," Tangney told NBC News.

'I think public shaming is going down the wrong path.'

She and her co-authors tested more than 400 prison inmates on their feelings of guilt ("I did a bad thing") vs. shame ("I'm a bad person") — and correlated the results with their likelihood to reoffend within a year. The researchers found that inmates who blamed others for their sense of shame were most likely to return to a life of crime. If the inmates accepted blame for their humiliation, they were less likely to get into trouble.

Tangney said punishments that emphasize guilt and making things right appeared to be still more effective.

"There are judges who are understandably trying to experiment with alternative punishments, because the current system isn't working very well," she said. "But I think public shaming is going down the wrong path. Community service sentences seem to be more likely to produce the desired result."

Would Cersei repent her ways if she were sentenced to community service? It's unlikely, considering how things work in "Game of Thrones." But who knows? George R.R. Martin still has time to write that plot twist into his next book.

For still more scientific angles on "Game of Thrones," check out our reality checks on riding a flying dragon, the zombie zeitgeist, death by being burned alive, torture by flaying, freakishly long winters, head transplants, lingering diseases and supposedly painless poisons.