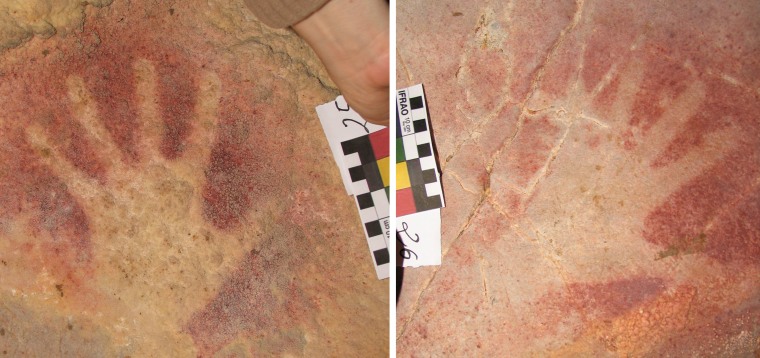

Alongside drawings of bison and horses, the first painters left clues to their identity on the stone walls of caves, blowing red-brown paint through rough tubes and stenciling outlines of their palms. New analysis of ancient handprints in France and Spain suggests that most of those early artists were women.

This is a surprise, since most archaeologists have assumed it was men who had been making the cave art. One interpretation is that early humans painted animals to influence the presence and fate of real animals that they'd find on their hunt, and it's widely accepted that it was the men who found and killed dinner.

But a new study indicates that the majority of handprints found near cave art were made by women, based on their overall size and relative lengths of their fingers.

"The assumption that most people made was it had something to do with hunting magic," Penn State archaeologist Dean Snow, who has been scrutinizing hand prints for a decade, told NBC News. The new work challenges the theory that it was mostly men, who hunted, that made those first creative marks.

Another reason we thought it was men all along? Male archeologists from modern society where gender roles are rigid and well-defined — they found the art. "[M]ale archaeologists were doing the work," Snow said, and it's possible that "had something to do with it."

In National Geographic, Virginia Hughes explains Snow's finding, published this month in American Antiquity. The new paper includes details from 32 stencils found in 11 caves in Spain and France, where some of the hand prints date back almost 40,000 years. Of the 32 stencils, 24 were likely female.

The new reading of the stencils "provokes a whole series of other questions," Snow said.

"What was the role of women in producing these," and, where else did they paint? "It may be that all we're seeing is the fraction of the art that survived," he said — paintings on exposed stone surfaces would almost undoubtedly have worn off over tens of thousands of years.

Over the last decade, Snow has been building evidence to show how the size of handprints and the relative lengths of fingers can tell us the sex of the artist who made them. He has also co-developed algorithms that can let computers scan and analyze prints quickly, and help identify the sex of the painters.

Other recent work on cave paintings has brought up the possibility that some early European cave art wasn't made by homo sapiens, but by our hominid cousins, the Neanderthals. Recent dating of the El Castillo cave in Spain, where some of Snow's prints came from, indicates that the very earliest cave paintings were made 40,000 years ago, when Neanderthals were still thriving in Europe.

New evidence and new research methods continue to alter and fill in our understanding of ancient societies. But one thing's for sure: As long as humans have been making art, we've been printing signatures by its side.

— via National Geographic

Nidhi Subbaraman writes about science and technology. You can follow her on Facebook, Twitter and Google+.