Donald Trump’s drastic and ongoing reconfiguration of the political landscape shows no signs of subsiding as November’s midterm elections approach.

This special report two months before the pivotal vote examines the impact of Trumpism on both political parties — their leaders, their candidates and their activists — as well as how it’s disrupting the political culture for voters.

Trump’s 2016 election and his presidency has been a cataclysm — an abrupt and brutal destruction of the existing political order.

That’s been satisfying for Trump voters. They clamored for a top-to-bottom shake-up of the status quo. Democrats frame his victory and its aftermath as a clarion call for action, while a class of lost Republican elites hopes the president’s seizure of the GOP is an anomaly from which their beloved party will someday recover.

Through dozens of interviews, an exclusive poll, an NBC News analysis of candidate websites and more, the picture has become clear: Democrats are moving further left; Republicans are gravitating toward Trump; and the voters increasingly disdain anyone who doesn’t agree with them.

This is the story of a jostled American electorate on the cusp of rendering its midterm judgment on the Trump presidency. That verdict will shape the final two years of his first term and provide valuable markers for the early contours of the 2020 political battleground that will decide whether the president will have four more years.

Democratic Enthusiasm Sows Division

OMAHA, Neb. — A gay bar may not be a typical campaign stop in ruby-red Nebraska.

But progressive upstart candidate Kara Eastman beat the typical Nebraska Democrat in a primary earlier this year, so one warm summer evening, she showed up at Flixx, a fixture of the nightclub scene in downtown Omaha, to greet supporters.

“There are people who are skeptical about an actual, unapologetic Democrat, running on a Democratic platform, because they’ve been trained to believe that this is not a winning strategy for this district,” Eastman, a social worker who runs a nonprofit, said in an interview. “I believe it is the winning strategy for this district. We have to ignite this base.”

With her all-in progressive platform of Medicare for All, free college and stricter gun control, Eastman breaks every rule about how Democrats should run in a place like Omaha. But after the 2016 election left her party with less power in Washington and in state capitals than it had in nearly a century, the old rules are being questioned.

Eastman is emblematic of the progressives, women and political newcomers who are remaking the Democratic Party for the post-Clinton-Obama era, outraged by Donald Trump’s election and fueled by a backlash to his administration’s actions.

The New Order

As progressives see it, the half-loaf incrementalism preached by Barack Obama and Bill Clinton had one job — to win — and it failed, so what good is it now? Better to demand it all, they say, and ask moderates to compromise, just as in the past moderates have asked progressives to move toward the middle.

“The question is always, ‘How are you going to get the Republicans to vote for you?’ The answer is we’re not,” said Crystal Rhoades, a close Eastman ally who leads the Douglas County Democratic Party, which includes Omaha.

That kind of thinking unnerves traditional Democrats, like the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, which backed Eastman’s opponent in the primary but ultimately decided to get behind her in the general election.

Some in the party see a rare opportunity to welcome disaffected refugees from Trump’s GOP, but progressives like Stacey Abrams, the Democratic nominee for governor in Georgia, and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who won the Democratic primary for a House seat in New York City, are more interested in capitalizing on the surging energy in their own base.

“It’s never been done here before,” Rhoades acknowledged. “We finally have a crop of candidates nationwide who are saying the things that need to be said, and they’re doing so unabashedly.”

For years, Rhoades has been trying to convince her colleagues that Democrats in Omaha are no different from Democrats in Los Angeles, so the party is better off giving its base what it wants than sacrificing its liberal values to try to win over Republicans.

Trump Supercharged It

Just as the tea party movement led to a reawakening of the right after eight years of Republican control of the White House, from 2001 to January 2009, the anti-Trump “resistance” has reinvigorated the left.

Progressives are protesting against their own party’s leaders and shifting the policy debate to the left, and the so-called establishment is listening. Tom Perez, chairman of the Democratic National Committee, even declared that Ocasio-Cortez, a self-described Democratic Socialist, “represents the future of our party” after she unseated a powerful congressman in a primary.

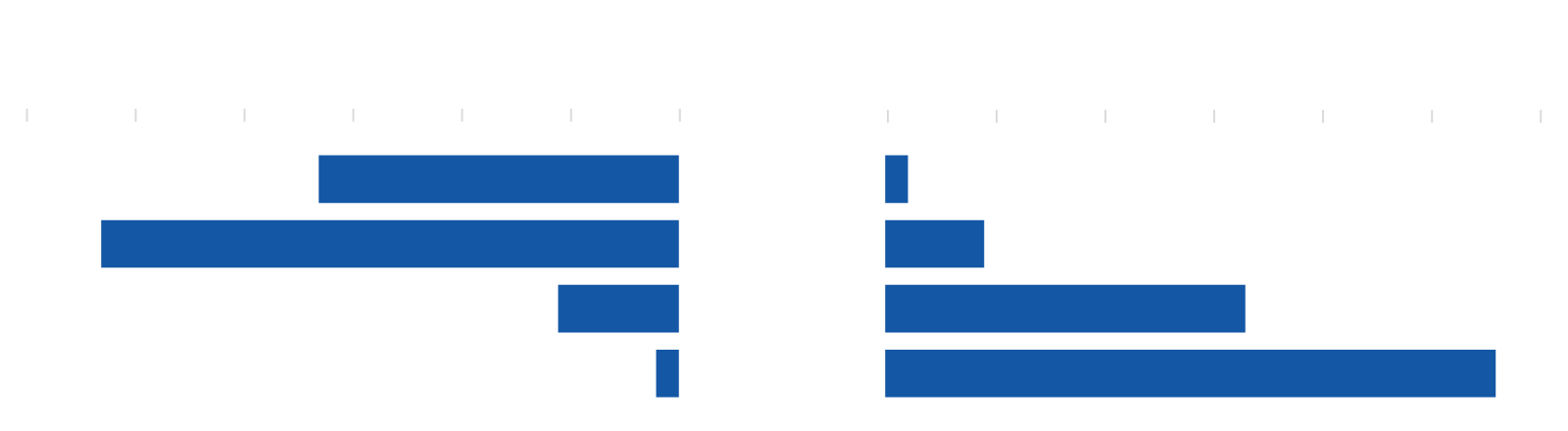

Exclusive poll: How Democrats say democracy is working, before and after Trump

Before Trump took office

Today

60%

50

40

30

20

10

0

0

10

20

30

40

50

60%

Very well

2%

33%

Somewhat well

53%

9%

Not too well

11%

33%

Not at all well

2%

56%

Before Trump took office

Today

60%

50

40

30

20

10

0

0

10

20

30

40

50

60%

Very well

2%

33%

Somewhat well

53%

9%

Not too well

11%

33%

Not at all well

2%

56%

Before Trump took office

Today

0

20

40

60%

Very well

Somewhat well

Not too well

Not at all well

Jake Sullivan, the top policy adviser in Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign, recently offered a mea culpa for not recognizing that the country was ready for a more muscular progressivism than he had anticipated.

“I have to confess that I did not fully appreciate the need for a more dramatic rethink at the start of the 2016 campaign,” he wrote in a lengthy essay for the journal Democracy.

Trump has only supercharged a hard shift to the left that was already under way.

When the president tried to repeal the Affordable Care Act, liberals responded by calling for single-payer health care. When Trump separated migrant families at the border, the left called for the abolition of ICE, the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency.

The most telling ideological shift in the party is the explosion of support for Medicare for All, an idea Clinton had dismissively brushed aside during the Democratic presidential primary two years ago as a “theoretical debate about some better idea that will never, ever come to pass.”

NBC News analyzed key issues on campaign websites of Democratic candidates

Medicare for All

30% back gov’t-funded health care

Gun control

71% mention the issue

Mention Trump?

43% do

In 2016, 62 Democrats in the House co-sponsored the main Medicare for All bill, which would replace the current health insurance system with a single-payer one. Now, more than 120 Democrats have signed on — nearly two-thirds of the caucus.

Single-payer health care has become the critical litmus test for any Democrat who wants to be seen as a progressive. Bernie Sanders used to be its only supporter in the Senate, but when he rolled out an updated version of the bill last year, he was joined by a who’s who of ambitious Senate Democrats: Elizabeth Warren, Cory Booker, Kamala Harris, Kirsten Gillibrand — all potential presidential hopefuls in 2020.

And it’s not just those usual-suspect liberals. Converts include at least four members of the moderate Blue Dog coalition and former Sen. Max Baucus, whom liberals blame for watering down the Affordable Care Act.

On social issues, there is now virtual unanimity among Democrats at the federal level on abortion rights and LGBTQ equality, in a way that would have been difficult to imagine just a few years ago. Obama didn’t back gay marriage until May 2012, deep into his first term and six months before he faced re-election.

As African-Americans have demanded more recognition from a party they loyally support, opposition to overhauling the criminal justice system has melted away. And on immigration, Obama’s deportations and Clinton’s opposition to driver’s licenses for undocumented immigrants now seem anachronistic as the party increasingly backs sanctuary policies and pro-immigrant positions to counter Trump. (Perhaps feeling the winds of change, Clinton announced she supported driver’s licenses for undocumented immigrants in 2015.)

Of course, moderates warn that the approach could end disastrously for Democrats, plunging the party into a 1970s and ʼ80s-style political slump.

But the country looks very different today.

When Walter Mondale lost 49 states to Ronald Reagan in 1984, whites made up 85.5 percent of reported voters and self-identified “conservatives” vastly outnumbered those calling themselves “liberals.”

Today, 73.3 percent of reported voters are white. And while the ranks of liberals in the party are rising fast, the number of Democrats who consider themselves conservative is falling.

Inside the party, the shift has come as it loses its former strongholds in the South, rural areas and small blue-collar cities.

Meanwhile, Trump has stripped Democrats of their interest in compromise.

More Democrats are more liberal

Democrats’ desire for compromise plummets

Moderate

Total

Liberal

Dem/Lean dem

Conservative

Rep/Lean rep

50%

80%

69%

60

40

46%

46%

The number of liberals in the Democratic Party is increasing, while conservatives and moderates are shrinking.

40

30

44%

The historical gap in which Democrats favored compromise more than Republicans has disappeared.

31%

20

20

10

10

0

0

2001

’03

’05

’07

’09

’11

’13

’15

’17

2011

’12

’13

’14

’15

’16

’17

’18

Democrats’ desire for compromise plummets

More Democrats are more liberal

Conservative

Liberal

Moderate

Total

Rep/Lean rep

Dem/Lean dem

50%

80%

69%

60

40

46%

46%

40

30

44%

The historical gap in which Democrats favored compromise more than Republicans has disappeared.

31%

20

20

The number of liberals in the Democratic Party is increasing, while conservatives and moderates are shrinking.

10

10

0

0

2011

’12

’13

’14

’15

’16

’17

’18

2001

’03

’05

’07

’09

’11

’13

’15

’17

More Democrats are liberal

Conservative

Liberal

Moderate

50%

40

30

20

The number of liberals in the Democratic Party is increasing, while conservatives and moderates are shrinking.

10

0

2001

’03

’05

’07

’09

’11

’13

’15

’17

Democrats’ desire for compromise plummets

Total

Rep/Lean rep

Dem/Lean dem

80%

69%

60

46%

46%

40

44%

31%

The historical gap in which Democrats favored compromise more than Republicans has disappeared.

20

10

0

2011

’12

’13

’14

’15

’16

’17

’18

For years, Democrats were far more likely than Republicans to say they wanted politicians who would work with the other side to get things done, but that gap has disappeared, according to the Pew Research Center.

Women Will Be Heard

When the freshmen of the 116th Congress assemble on the steps of the Capitol in January for their class photo, the most notable difference from every portrait hanging next to it will probably be the number of women present.

There are now more women running, donating and winning primaries than ever. That surge is limited to the Democratic side, two years after a man accused of sexual assault beat the first woman nominated for president by a major party, a result that helped give rise to the #MeToo movement.

“Women are tired of handing their politics over to men and seeing it not get done,” said Jane Kleeb, the chairwoman of the Nebraska Democratic Party. “Women have reached their tipping point.”

That helps explain Eastman’s win, Kleeb said, and it helps explain numerous other races where women beat expectations to win Democratic primaries this year.

Women have won about 65 percent of Democratic primaries this year for open House, Senate and governor seats that included at least one man and one women, according to an analysis by FiveThirtyEight.

In 2012 and 2014, women were about equally likely to donate to Democratic candidates or liberal groups as they were to Republican and conservative ones. As of earlier this year, however, 68 percent of women’s political contributions are going to Democratic candidates or liberal groups, according to Open Secrets, a project of the Center for Responsive Politics, a nonpartisan nonprofit that tracks money in American politics.

Activism On the Rise

The force powering all of this, of course, is the backlash to Trump.

“I shouldn’t thank him, but I do,” said Precious McKesson, a community organizer in heavily African-American North Omaha, the birthplace of Malcolm X.

McKesson was deeply involved with social welfare groups in her community, but she didn’t pay close attention to politics until after the 2016 election, when she noticed the drop-off in votes from African-Americans.

She complained to party officials that Democrats had a habit of ignoring black voters until election season — “we’re the break-glass-in-case-of-emergency vote,” she said — so the state party put her in charge of outreach to the community.

Two years ago, she supported Clinton, like the vast majority of black Democrats. “But if I could go back and do it again, I would very definitely vote for Bernie,” she said of Sen. Bernie Sanders, the Vermont independent who challenged Clinton in the primary and may run again for the White House in 2020.

McKesson is just one of thousands of Americans who became political activists — and candidates — because of Trump.

Explosion of activism: A new breed of Democrat rises in a red state

For the first time in years, Democrats have fielded candidates in every congressional district in states like Texas and Alabama, where they used to not even bother competing.

Three years ago, just 19 percent of Republican lawmakers were facing Democratic challengers who had raised at least $50,000, a sign of viability. At the same point in this cycle, 58 percent of GOP incumbents faced challengers who met that threshold.

ActBlue, which processes online payments for most Democratic candidates and groups, has run out of superlatives as they smash through fundraising record after record.

That enthusiasm and energy will be the hardest thing for Democrats to sustain.

And many worry the party’s leftward lurch will be an even bigger liability for Democrats in 2020 and perhaps beyond.

“We have a tendency to alienate rather than to welcome,” said Rep. Jim Himes, D-Conn., the chairman of the moderate New Democrat Coalition.

But for Eastman, the realignment is worth the risk.

“I always thought people like me don’t get elected,” she said. “But I think people are looking for authenticity and integrity in their candidates. You might not agree with me on every issue, but I won’t lie to you, and I have nothing to hide.”

‘Trump Tribalism’

INDIANAPOLIS — On drives to visit his timber properties around Jasper, Indiana, in late 2015 and early 2016, Mike Braun began to see “signs” that a wealthy businessman with relatively little political experience could capture the imagination of Republican voters.

The signs said “Trump.” And they cost $16 for a set of two on the Trump campaign website. Braun, who was serving in the state legislature at the time, marveled that a candidate could become fashionable enough to sell campaign placards.

“I mean, people are not going to pay for a sign for any politician unless there was something going on,” Braun, who is now the GOP’s Senate nominee in Indiana, said in an interview with NBC News.

Locked in a tight race that could help determine which party controls the chamber come January, Braun, who defeated two Republican congressmen in the May primary to earn a shot at Democratic Sen. Joe Donnelly, has grasped a simple truth: The ethos of modern Republican voters is a tribal loyalty to Trump.

“Trump does not go simply for the intellect, but also the gut and the heart,” Steve Bannon, who served as chief executive on Trump’s campaign and then as a top adviser at the White House, said in an interview.

The Republican Party is vastly different now than it was from GOP presidential primaries dating back at least as far as George H.W. Bush.

Evolution of anger: The tea party in the age of Trump

The shifts, manifested most obviously in Republicans’ drastically increased antipathy toward the federal government, didn’t happen overnight. But Trump, unencumbered by decades of votes in Congress or a policy record as a governor, came along at just the right time to capitalize on, and accelerate, them.

He represents an apotheosis of the tea party, and, with his primary and general election victories, he largely subsumed that movement into his political base. Victory also brought along a substantial portion of the establishment of the GOP.

Exclusive poll: How Republicans say democracy is working, before and after Trump

Before Trump took office

Today

50%

40

30

20

10

0

0

10

20

30

40

50%

Very well

5%

42%

Somewhat well

18%

42%

Not too well

39%

11%

Not at all well

37%

4%

Before Trump took office

Today

50%

40

30

20

10

0

0

10

20

30

40

50%

Very well

5%

42%

Somewhat well

18%

42%

39%

Not too well

11%

Not at all well

37%

4%

Before Trump took office

Today

0

10

20

30

40

50%

Very well

Somewhat well

Not too well

Not at all well

Trump’s approval rating among Republicans stood at 88 percent in an NBC/Wall Street Journal poll conducted in July, a staggering figure for a president whose standing with the broader electorate remains underwater.

“He changed the Republican Party by just winning, quite frankly, an election that most of us thought we probably were not going to win,” said Rep. Tom Cole of Oklahoma, a former chief of staff of the Republican National Committee. “In my last election, I got 70 percent and he got 66 in my district, and if we get into an argument, he’ll keep his 66 and I’ll keep my 4.”

Standing With the President

Braun has bet his candidacy on Indiana voters retaining their enthusiasm for Trump, whom they favored by nearly 20 percentage points in 2016.

Braun’s key to beating Donnelly, who won his seat the same year Republican Mitt Romney beat President Barack Obama by 10 points in Indiana, is making sure base GOP voters come to the polls without alienating moderates so much that they cross the aisle to re-elect Donnelly.

For each GOP nominee in a competitive House, Senate or gubernatorial race, that calculus is a little different. It depends on the leanings of the district or state, as well as those of the candidate. One variable, even on heavily Republican turf, is the degree to which candidates emulate Trump’s histrionics, as Rick Saccone did in losing a House special election in western Pennsylvania and Brian Kemp did in winning Georgia’s GOP gubernatorial nomination. Some, like Braun, have chosen to embrace the president’s anti-Washington message and his policies but not his idiosyncrasies.

In Indiana, a state with a strong Republican lean and Midwestern sensibilities, Braun says he’s in line with the “essence” of Trump, but not the president’s style.

Republicans in Transition

Trump has shown a knack for giving political thrills to nearly all the factions within the Republican Party, plus a set of Trump Democrats who share his nationalist views on immigration, trade and foreign policy.

For example, he demonstrated his support for Israel by deciding to move the U.S. Embassy to Jerusalem from Tel Aviv, an important sign for the evangelical Christians who are the swing voters of GOP primaries — capable of voting for candidates across the ideological spectrum and whose participation levels in general elections can make the difference between victory and defeat for Republicans.

NBC News analyzed key issues on campaign websites of Republican candidates

Taxes

90% favor cuts

Obamacare

51% support repeal

Build a border wall

Just 10% back the idea

Trump’s shorthand for cracking down on illegal immigration is “build the wall,” which capitalizes on a long-running push from hard-liners to address border crossings with a physical barrier, and plays on fears of immigrants among some Republican voters.

Much of his talk on cultural matters, from NFL players who don’t stand for the national anthem to the intelligence of prominent African-Americans, activates racial resentments among some of his supporters.

But among supporters, if he has to change his position on an issue, they will move with him. “They’re prepared to understand that he’s going to have tactical retreats now and then,” Bannon said.

Noting that Trump is pushing the GOP toward a brand of populist nationalism that was anathema to previous party heads, Bannon said, “He’s the only political leader in the country who’s trying to take his base to a different place.”

On one hand, major elements of Trump’s “America First” framework represent an effort to redirect the whole of the Republican Party away from multilateral trade, liberalized immigration laws and dollar diplomacy.

But on the other hand, Trump was also able to articulate a vision for the country that merged seamlessly with existing trends inside the party. His “drain the swamp” attack on Washington came the same year Gallup polling showed that 82 percent of Republicans believed the federal government had too much power, compared with 39 percent in 2002. (In 2017, 66 percent said they believe the government has too much power.) Over the same time period, the share of Democrats who think that has remained steady.

And on issues of personal morality, the GOP has, along with Democrats, become much more accepting of divorce, having children out of wedlock and other social issues. Those trends explain why the “family values” party nominated and elected a twice-divorced man on his third marriage and has stuck with him despite allegations that he paid hush money to two women who claim they had affairs with him.

The Republican movement on Trump’s signature issue — immigration — has been smaller, but significant enough to yield a clear majority of GOP support for clamping down.

Those numbers also don’t capture the much more clear aversion Republican voters have to illegal immigration, which is evident in near-universal GOP support for Trump’s wall, even among voters who are comfortable with creating a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants who are currently in the country.

Trump’s temperament isn’t always popular with Republicans, but the policy outcomes of his presidency have unified the GOP.

“They see all the things that have flowed out of that: Supreme Court appointments, the tax cut, probably the most deregulatory Congress in modern American history,” Cole said.

Loyalty Above All Else

Tom Schultz has numbers that explain why Trump’s critics feel so frustrated when they see him get a pass from GOP voters and lawmakers after he takes a position seemingly at odds with his base or long-standing conservative orthodoxy.

Schultz, who was the data director for the 2016 presidential campaign of Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, and now works as vice president for digital and analytics at the conservative Club for Growth, found that the majority of GOP voters want Republicans in Congress to support Trump’s policies, even when the voters themselves disagree with those policies.

He’s measured that sentiment using a proprietary “Trump Tribalism” score based on an index of voter responses to various questions, including the degree to which they change their own responses on issues based on where Trump stands on them — regardless of whether it’s to the left or right of their initial feeling.

Braun, the Indiana Senate candidate, demonstrated in July how that works.

Just before Trump announced he would extend $12 billion in subsidies to help farmers offset the pain of retaliation against his tariffs, Braun told NBC News he opposed an infusion of federal funds into the agricultural sector. The next morning, Braun sent a statement to NBC saying he supported Trump’s subsidies. The reversal, from a Trump-aligned candidate for the Senate, was a perfect example of the dynamic Schultz has measured among the president’s backers.

“There’s clearly a large segment of Republican voters who value loyalty to Trump above all else,” Schultz said.

Back Home Again in Indiana

At this point, there’s little argument among Republican and Democratic political strategists that Trump has consolidated his party’s base as completely as any president of either party has ever done.

The question heading into the midterms is whether turnout, which tends to play a bigger role than in presidential elections, will help Republicans keep control of the House and Senate.

Gallup data suggest that while Trump’s base of supporters is locked in, so are his critics in both parties. Indeed, his approval ratings have been more static — and lower — than any president since Harry Truman.

That’s true despite unambiguously strong economic indicators, from a stock market that has soared during his presidency to stunningly low unemployment numbers and a second-quarter GDP growth rate of 4.2 percent — the highest in four years.

Because of Trump’s loyal base, there’s little choice for most Republican candidates but to stick with him. To show a degree of distance, Braun emphasizes that his style is much more humble and less bombastic than the president’s.

In Indiana, where the Republican tilt is strong — as it is in several other states with toss-up marquee races, including Montana, North Dakota, Missouri and West Virginia — that might be enough if the GOP base is motivated to go to the polls.

And Trump, who clearly understands he is the overarching issue in the midterms, is leaving nothing to chance. He said that he plans to spend six to seven days a week on the campaign trail from Labor Day to Election Day, working to energize his backers on behalf of Republican candidates.

For them to take advantage, many will make the same gamble that Braun has: leave no daylight between themselves and a Trump agenda that fully defines the modern GOP, even when it changes.

In a show of just how much his candidacy reflects the sentiment of Republican base voters, Braun paused for a few beats before answering whether there’s any issue on which he disagrees with Trump.

“Not really,” he said.

Contempt For The Other Guy

WASHINGTON — For Sen. Marco Rubio, the rise of Trump prompted an existential crisis.

“My whole life I have been told no matter how you may feel about someone, you respect everyone because we are all children of the same God,” the Florida Republican said at one of the last events of his presidential run two years ago. “Now being respectful to one another is considered political correctness.”

Political scientists think Rubio is onto something.

Voters can stay connected to news 24/7 through their phones, but they’re living more isolated lives politically, geographically and socially — and, increasingly, they just don’t like one another.

Researchers interviewed by NBC News say this development is the most important factor undergirding American politics. It’s called “negative partisanship” and it’s a phenomenon in which voters base their decisions less on which party they like and more on which party they fear and loathe.

Breaking down the 2018 campaign ads

“The most consequential trend in American public opinion in at least the last 20 years is people’s increasing dislike for the other side,” said Carolyn Roush, a fellow at the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation at the Harvard Kennedy School. “That far precedes 2016.”

Negative partisanship is one of a series of trends that continue to reshape politics in 2018.

Americans have become more partisan, but also more distrustful of the two major political parties, whose power has been challenged by grass-roots movements from below and deep-pocketed donors from above.

Candidates on the left have become more consistently liberal, while those on the right have turned more consistently conservative, giving citizens a clearer choice but making compromise once in office more difficult and political conversations more heated.

For decades, researchers have conducted “thermometer” surveys asking Americans to gauge their warmth toward various groups and political actors, often on a 1-100 scale. People’s view of their own party has remained relatively consistent at a comfortable temperature of about 70 degrees.

But in recent years, their rating of the other side has plummeted: Republican and Democratic voters pegged the rival party at a frigid record low 23 degrees in 2016, according to data from American National Election Studies compiled by Emory University political scientists Alan Abramowitz and Steven Webster, down from the mid-40s in 1980.

The NBC News/SurveyMonkey thermometer poll found that 49 percent of Democrats and Democratic-leaning voters gave the other party a “zero” rating in July, a spike from 39 percent who did so in a January 2016 poll. Republican contempt for the other side remained steady, with 42 percent of GOP or GOP-leaning respondents giving the Democratic Party a “zero” rating.

This may feel intuitive to those watching campaigns play out: Trump has bashed his GOP leaders and flip-flopped on policy while maintaining strong support from his party. Republicans unite behind his relentless attacks on shared targets like Hillary Clinton, NFL protesters and immigrants, which have carried over to 2018 campaigns with similar messages. On the Democratic side, close to 60 House candidates this year have indicated they will not support Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi for speaker if they win the House, with little apparent penalty from Democratic voters eager to challenge Trump’s agenda.

There’s a debate about what is causing this shift toward more divisive campaigns. Part of it is that, as this year’s candidates demonstrate, parties are easier to distinguish. It’s hard to imagine today, but not long ago a significant minority of Republican voters were rated in issue surveys as more liberal than the median Democrat voter and a slice of Democratic voters were rated as more conservative than the median GOP voter.

You can see this in the sharp decline of “ticket splitting,” where a voter picks one party for the White House but the other party for Congress or governor.

The number of congressional split-ticket districts hit a record low in 2012 and was only marginally higher in the last election. And 2016 was the first time that voters chose the same party for Senate and president in every single state, according to the University of Virginia Center for Politics.

The candidates reflect this declining pool of swing voters as well — even relative centrists running in 2018 check most major boxes on party policy. In many conservative-leaning states, you can find progressive candidates like Rep. Beto O’Rourke, the Democratic Senate nominee in Texas. In a more extreme case on the other side, the GOP’s nominee in blue-leaning Virginia, Corey Stewart, is a Confederate flag enthusiast popular with white nationalists.

But much of the divide goes beyond individual issues and toward racial, religious, geographic and class identity. Rural, evangelical and white voters without a college education are much more likely to be Republican. Nonwhite, urban and college-educated voters are much more likely to be Democrats.

There’s also a massive generation gap that didn’t exist in elections as recently as 2000. A Pew Research survey in March found 59 percent of millennial voters identify or lean Democratic while 52 percent of voters in the Silent Generation (those in their 70s and 80s) identify or lean Republican.

“Partisanship is increasingly connected with deeper divisions in American society,” said Abramowitz, the political scientist at Emory University who studies polarization. “It’s almost impossible to reach across the aisle because the differences are so great.”

With faith, ethnicity and geography becoming bigger predictors of one’s vote, elections are also becoming stand-ins for more personal feelings, rather than choices about policy. Voters increasingly see their selection of a candidate as an affirmation of their core identity and a vote for the opposing party as an attack on that identity.

Seventy-one percent of voters in the NBC News/SurveyMonkey poll believe a person’s political views “say a lot about their character,” including 80 percent of Democrats and 68 percent of Republicans. A substantial minority of partisans, especially Democrats, also report misgivings about relationships with people from the opposite party. Thirty-six percent of Democrats say they’re “not too comfortable” or “not at all comfortable” having close Republican friends. Twenty-one percent of Republicans report the same about Democrats.

Comfortable having close friends in the other political party?

Democrats

Republicans

50%

40

30

20

10

0

0

10

20

30

40

50%

26%

44%

Very comfortable

37%

35%

Somewhat comfortable

26%

Not too comfortable

16%

10%

5%

Not at all comfortable

Democrats

Republicans

50%

40

30

20

10

0

0

10

20

30

40

50%

Very comfortable

26%

44%

37%

35%

Somewhat comfortable

Not too comfortable

26%

16%

Not at all comfortable

10%

5%

Democrats

Republicans

0

10

20

30

40

50%

Very comfortable

Somewhat comfortable

Not too comfortable

Not at all comfortable

“We have these very negative perceptions of other side and don’t want to associate with them,” said Abramowitz, the Emory professor.

Having parties with such stark differences can make politics more brutal. But it also can make choices more coherent, and there are plenty of voters, activists and politicians who aren’t mourning the good old days of center-right and center-left senators hammering out deals over drinks.

On the left, Democrats see an opportunity to rally behind more sweeping proposals on issues like health care and immigration without having to worry about alienating right-leaning Democrats or attracting a Republican swing voter or two. As the party becomes less reliant on conservative white voters, activists also see an opportunity to put issues of racial justice and equality on the agenda in ways that party leaders might have previously discouraged.

“The fact that you have Stacey Abrams leading the ticket in Georgia, I can’t even imagine something like that happening 25 years ago,” said LaTosha Brown, co-founder of the Black Voters Matter Fund.

Abrams, a Democrat, is the first black woman to win a major party nomination for governor and has run an unabashedly progressive campaign.

And true to national trends, her opponent Brian Kemp is proudly running as a “politically incorrect conservative” — he has run ads in which he points a gun at a teenage boy who is dating his daughter and pledges to personally “round up criminal illegals” in his truck.

On the Republican side, some see the party’s hard right turn on immigration as more reflective of its base, whose demands had previously been bottled up by donors and party leaders in favor of less popular ideas like cutting Medicare and Social Security benefits to balance the budget.

“The No. 1 thing that’s changed since 2016 is that the party has migrated to better reflect the views of its actual voters,” said John Feehery, a former House Republican leadership aide.

Others, especially with more heterodox politics, feel left behind in the shuffle.

A Last Word

Reed Galen climbed the heights of Republican politics, following George W. Bush from the governor’s mansion in Texas as a 2000 campaign staffer to the White House as an aide and later serving as deputy campaign manager on John McCain’s 2008 presidential run. His politics were a mix — he veered further left on guns than most of his fellow Texans, for example — but Bush appealed to him with his emphasis on education and positive spin on immigration.

After 2016, however, Galen decided he was no longer welcome in either party.

“Trump was the straw that broke the camel’s back,” he said. “If this is what it takes to be a Republican or to win a Republican nomination, this isn’t who I want to be.”

So he tried another route: He joined a handful of other disaffected Bush veterans and a Wall Street backer to launch a small third-party group, the Serve America Movement, in hopes of cultivating candidates with similarly mixed views and even changing laws to expand voter participation and encourage a more diverse set of candidates to run.

He’s not expecting results anytime soon. The goal is gradual change over years, even decades, to slowly nudge Americans back toward one another. For now, though, he’s stuck in the Trump era.

“You can kick a barn down in 15 minutes,” Galen said. “It takes weeks to build a new one.”