The Food and Drug Administration knew that some doctors were wrongly prescribing powerful opioid painkillers but did nothing to investigate or even stop them, researchers said Friday.

The drugs include mouth sprays and lozenges meant to provide immediate relief for breakthrough cancer pain — a sudden spike in pain — in patients who have been taking opioids for long periods of time and who have developed a tolerance for them.

The drugs are very potent, often as much as 100 times stronger than morphine. The formulations, referred to as transmucosal immediate-release fentanyl products, or TIRF products, can kill patients who take them without having first developed tolerance.

But they were prescribed to patients who had no tolerance, and for migraines or dental pain, the team at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health said. Many providers who were supposedly trained in the proper use of the drugs gave incorrect answers on surveys about their use.

“There are some doctors who are clearly prescribing it wrong,” Dr. Joshua Sharfstein, a former FDA deputy commissioner who was part of the study team at Johns Hopkins, told NBC News.

“And FDA did nothing to stop them.”

The U.S. is suffering through an epidemic of opioid abuse. Opioids, including prescription opioids and heroin, killed 42,000 people in 2016, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

At the same time, the CDC reported last year, the number of prescriptions for the painkillers tripled from 1999 to 2015.

The FDA, CDC and other medical groups agree that the crisis has been driven in no small part by overprescribing.

One subset of these drugs is so powerful and so dangerous that the FDA set up a special plan to control their use, called a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy.

It is designed “to mitigate the risk of misuse, abuse, addiction, overdose, and serious complications due to medication errors,” the FDA said in a statement.

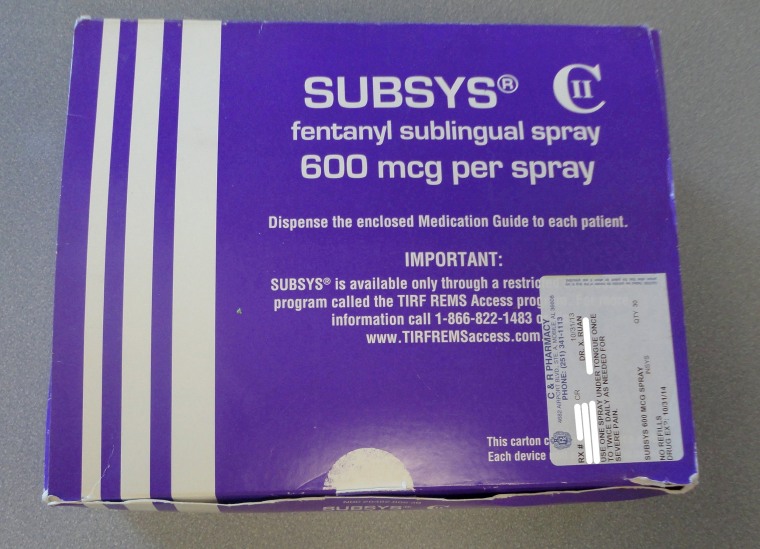

The products include Actiq, a kind of lozenge or lollipop that delivers fentanyl under the tongue for quick absorption, and Subsys, an under-the-tongue spray.

The FDA asked one of its expert panels to meet Friday in Silver Spring, Maryland, to help review how the strategy for the TIRF opioids has been working.

It has not worked as designed, the Johns Hopkins team said in testimony given to the panel.

The strategy has "generated red flags for years," the team said in written testimony. "There have been multiple warnings that many providers have been engaged in inappropriate prescribing, placing patients at risk."

The team used Freedom of Information requests to gather the FDA’s own documents and show that the agency did little or nothing to investigate the misuse of the opioids.

“FDA had evidence as early as April 2016 that TIRFs were being prescribed for many patients who were not opioid tolerant,” they wrote in their testimony.

“This evidence includes an analysis of commercial health plan claims, provided to the agency on April 25, 2016, indicating that of more than 25,000 patients receiving TIRFs, as many as 51 percent were not opioid tolerant (with follow-up analyses showing that ‘only 44.6 percent to 65.4 percent appear to be opioid tolerant.)’ ”

FDA Commissioner Dr. Scott Gottlieb said he was taking the questions seriously.

"Important feedback today: there are gaps in data on use of these products and adverse events," he said in a series of comments on Twitter.

Usually, the FDA stays out of medical practice. For most drugs, once they are approved, a physician may prescribe them for any purpose.

But when a risk evaluation strategy is in place, the FDA has more control, Sharfstein said.

“With drugs this risky, the FDA has to get directly involved in the practice of medicine,” he said. “They can kick doctors out of the program, meaning they can never prescribe it again.”

The program also requires prescribers to undergo training in proper use of the drug.

But despite clear evidence that some doctors were ignoring the guidelines, the FDA did not act, Sharfstein said.

“What we found was that there wasn’t a single prescriber reviewed, let alone decertified,” he said.

Why not? Sharfstein speculated that perhaps the FDA expected the drug companies whose products were covered by the risk protocols to keep a closer eye on prescriptions.

"They may not have known what they were up against," he said.

Usually, he noted, when a drug has risk restrictions in place, the companies are eager to make sure the directions are followed, because they do not want to see patients harmed by their drugs.

However, opioid makers have been accused of deliberately overselling their products. They have even been sued by many cities and states.

Gottlieb said in a statement earlier this week that the program had appeared to be working as intended.

Since the risk protocols were implemented, "there has been a significant decline in prescribing of TIRF products, and currently they are only prescribed to approximately 5,000 patients nationwide,” he said. But, he said, the FDA was asking its advisers Friday to recommend ways to make the system work better.

Several committee members expressed concern that one survey for the FDA showed that only about 77 percent of doctors, pharmacists and other professionals fully understood the restrictions on the TIRF opioid products.

“You can’t imagine asking a doctor where the liver is and having an only 80 percent chance of getting it right,” Dr. Lewis Nelson, chairman of the emergency medicine department at Rutgers University in New Jersey, said at the meeting.

“With a drug this dangerous, I think you need 100 percent,” he added. “I think we need more control, not less.”

But others said it wasn't really clear which patients were getting prescriptions for the powerful TIRF opioids.

The CDC has issued guidelines recommending that doctors cut back on opioid prescriptions in general, and advising patients to try anything else they can before asking for the powerful and addictive drugs.

Dr. Caleb Alexander, who heads the Center for Drug Safety and Effectiveness at Johns Hopkins, said his team’s findings were sobering.

“The FDA has an important opportunity to better regulate these products,” he said in a telephone interview.