WAREHAM, MASS — When Dr. Jason Reynolds learned that one of his teenage patients was in the emergency room after overdosing on heroin, he was stunned. Reynolds had been Nate Morse's pediatrician since the boy was 6.

Now, he wondered what he could do for Nate, who was still not 21. "I remember leaving the room and thinking, OK, where are we going to find help for you?" Reynolds told Today's Kate Snow. "And how are we going to help you with this? And really, there's not a lot."

Reynolds had just found one of the big holes in addiction treatment: Most programs are designed for adults and won't take adolescents. Few programs are targeted to someone as young as Morse, who had become hooked on opioids after getting pain medication for a soccer injury and first overdosed at 19.

With overdose deaths among teens on the rise, that treatment hole has become all the more important to fill.

"It's very hard for kids to get treatment," said Dr. Sharon Levy, one of the nation's few pediatric substance abuse specialists. Levy, who practices at Boston Children's Hospital, realized that there was a need to give more pediatricians the training they would need to treat addiction.

"There are 750,000 physicians in this country who can prescribe pain medications, while there are only 37,000 who can prescribe the medication to treat people who have an addiction to pain medications," Levy said. "And only 1 percent [of those 37,000] are pediatricians. So there is a real gaping hole when it comes to getting these medications out to the kids who need them."

Related: Teens Showing Up in ER Addicted to Opioids

In an effort to change that, Levy asked Reynolds and Wareham Pediatrics to launch a pilot program designed to give pediatricians the training they would need to prescribe medications that could help teen addicts to get clean.

“It makes it a lot easier for parents," said Jonas Bromberg, a clinical psychologist at Wareham who helped launch the program. “It's the idea that they're coming to this very familiar, safe place where they've had this long relationship. They don't need to go to a drug treatment program where there’s that kind of stigma involved. It's just going to the doctor's office."

In March, after Morse had overdosed a third time, Reynolds put the teen on a low dose of an opioid medication called suboxone, which blunts craving while avoiding the highs and lows of drugs like heroin.

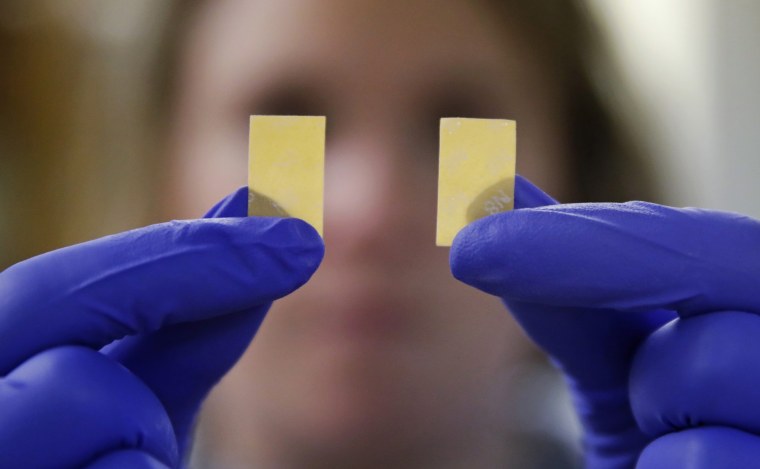

"It doesn't make you feel high," Morse said. "It looks like a Listerine strip. You put it under your tongue. It tastes awful. It's brutal, but it works. It gets away all my cravings. Like I haven't had a single craving since I've been on this."

Being treated by his longtime pediatrician rather than in a hospital made everything easier for Morse. "It's completely relaxed," Morse said. "I feel like I'm at home."

'Everyone I Knew Around Me Was Dying'

Cora Porter wishes she could have been treated by her own pediatrician.

Porter started taking painkillers when she was 15 and by her senior year of high school she was singing in the choir, playing string bass in the school orchestra — and shooting heroin like many of her friends.

As more and more of them overdosed, Porter got scared. "Everyone I knew around me was dying and I knew it would have been me next," she said. "I almost reached this crossroads where I couldn't picture myself with drugs and I couldn't picture myself without them because it was so painful."

Porter's mom, Carol Allen, was scared too. "It's mortifying and gut wrenching," Allen said. "You want to cry all the time, but you have to stay strong because your child is ill. And we treated it as an illness from day one. There was never any anger, any stigma, any anything. We just dived in with both feet."

Allen's attitude comes from an understanding of what opioids do to the brain.

"Addiction is the result of neurologic changes," Levy explained. "It really is an acquired brain disease. And the medications can treat that. They can make patients better. I've been doing this for more than 15 years and I have seen kids really turn their lives around."

Those changes in the brain are what justify treating an opioid addiction with another opioid. "When they stop using [the drugs] their brain is different and it's no longer responsive to the body's own chemicals," Levy explained. "And so, what happens is people get cravings."

While the cravings eventually disappear, other brain changes result in a loss of the ability to control behavior, Levy said. "And that's a problem that goes on for a very long time," she added. "So once they're addicted, they really lose control and their use of drugs almost becomes obsessive."

With the help of the program at Boston Children's Hospital, Porter got clean and she's been sober for six years.

The American Academy of Pediatrics is now urging pediatricians to treat patients for substance abuse. But that can only happen if pediatricians get the training they need. As far as Reynolds is concerned, that's all important. "It's what the community needs," he said. "We're dealing with a crisis."

The downside of not addressing the problem is huge. "Kids who have opioid-use disorders who don't get treatment — 90 percent or more of them will continue to use drugs," Levy said.

Bromberg recognizes that there are pediatricians who won’t immediately feel comfortable taking on addiction treatment. “I would say to those pediatricians that are hesitant, think about your role as a kid's health care provider," he said. "This is just as integral to their health as any other sort of condition you're going to treat them for."

The treatment Morse got put him back on track. Without it "I would probably be homeless, not able to go back and live with my family and get a second start," he said. "I want to be able to help people and explain there is help and there's no need to give up."