Jeff Bauman was waiting for his girlfriend to cross the finish line of the Boston Marathon on a brisk April afternoon when he saw a young man in a black baseball cap and sunglasses who looked like he didn’t belong.

“I remember this kid standing next to me,” said Bauman. “He just seemed out of place. Everybody there was having fun, you know, clapping, taking pictures, and he was just standing there with a backpack.”

Minutes later, at 2:49 on April 15, 2013, two bombs hidden in backpacks exploded within 13 seconds of each other, sending shrapnel tearing through the packed crowd near the marathon’s finish line on Boylston Street. The blasts killed three people and wounded 264 others, including Bauman, and launched a regionwide manhunt that ended more than 100 hours later in a suburban backyard.

Watch the Brian Williams special “108 Hours: Inside the Hunt for the Boston Marathon Bombers” tonight at 8 p.m. ET.

The next four days, Boston Police Commissioner Ed Davis told NBC, were “frenetic, intense.”

“We had people out there with evil intent,” said Davis, “that we felt were still dangerous. And it was really important to get them quickly.”

Through interviews with survivors, law enforcement officers and witnesses, NBC has retraced the frantic hunt for the perpetrators.

--------

After the explosions, Davis rushed to the race’s finish line. “I saw a scene of devastation,” he recalled. “It was a battlefield scene.”

The backpacks had been stuffed with ball bearings and nails, which sprayed outward, tearing the flesh from spectators. Fourteen people would lose limbs to the bombs.

Jeff Bauman thought something had gone wrong with a firework, since the blast had blown him off his feet. Then he looked down at what had become of his legs.

Celeste Corcoran, who was at the finish line to watch her sister Carmen complete her first marathon, was knocked to the ground, her legs shredded and both eardrums blown out.

Celeste’s daughter, 17-year-old Sydney, lay on the pavement gravely injured, the femoral artery in her right leg severed by a huge chunk of shrapnel. But in a scene that would be repeated again and again, a stranger rushed to help her.

“The next thing I remember is I’m flat on my back, looking up and there’s a man who has his forehead to mine. And he’s telling me, like, that it’s going to be OK,” said Sydney. The stranger and another man ripped up shirts to make tourniquets and tie off her leg.

Sydney, Celeste and Bauman were all rushed to local hospitals. Sydney didn’t know what had happened to her mother, and was unaware she was in the same hospital, Boston Medical Center, headed for emergency surgery.

Celeste had to sign a piece of paper authorizing the removal of the remains of her legs. “I just looked at [the doctor] and said, ‘Both of my legs?’” recalled Celeste. The doctor said yes. Celeste signed the paper. “All I could think of was that I needed the pain to go away.”

Back at the scene of the explosion, Commissioner Davis had put a 15-square-block area under lockdown and asked the FBI for help.

Rick DesLauriers, who was then the FBI’s special agent in charge in Boston, had just spotted the billowing smoke about Boylston from his office when Davis called. Recalled DesLauriers, “Ed [said], ‘Send your bomb techs and SWAT teams down here as soon as possible.’”

Within hours of the bombing, the FBI had become the lead agency and the investigation had become federal.

Evidence technicians sifted through the glass and blood and bits of clothing.

“They know what to look for,” said Davis. “Within the first hour, there had already been a piece of the detonating device that had been identified and secured.”

That discovery, along with evidence indicating the bombs were made of pressure cookers stuffed with shrapnel, confirmed Davis’s suspicion that terrorists had struck. Searchers would also find black nylon from a backpack.

Davis had been in the crowd earlier that day watching the race, and had noticed just how many spectators were taking stills and video with their mobile phones. “I was confident that no one could make their way through that course without being picked up on photos,” said Davis.

On Tuesday morning, DesLauriers made a televised appeal for anybody who’d been near the finish line to send in their images and footage to help find the perpetrators. Investigators were soon inundated with clues, and more than 120 analysts and agents at the FBI lab in Virginia reviewed the photos.

Meanwhile, the first big break in case came that same morning, 24 hours after the race had begun.

Jeff Bauman woke up after surgery, fighting through a fog of medication. “It was horrible. I couldn’t even move,” said Bauman. He was burned all over, his legs were gone, and he had a hole in one of his arms. Tubes in his mouth prevented him from speaking.

But he motioned for a pen and paper and wrote down a message.

“Saw the guy,” wrote Bauman. “Looked right at me.”

By Tuesday morning, investigators knew that three people had been killed in the explosion: Krystle Campbell, 29, a restaurant manager from Medford, Mass.; a Boston University graduate student from China named Lu Lingzi; and 8-year-old Martin Richard of Dorchester, Mass., who’d been watching the race with his family.

Davis knew that the perpetrators were still at large, but didn’t know if they hoped to claim more victims.

Detectives at Boston Medical Center, however, told authorities that a seriously injured patient was giving a detailed description of a credible suspect. With Bauman’s tip, investigators were able to speed up the analysis underway at the FBI photo lab.

By Wednesday morning, less than 48 hours after the blast, Davis says, investigators had “faces.” The two men they would later identify as the Tsarnaev brothers could be seen in the collected imagery, wearing baseball caps, hooded sweatshirts under dark jackets, and carrying backpacks.

There was video from up and down the race course, but the footage from a camera at a store on Boylston Street near the site of the second blast would prove crucial.

According to DesLauriers, a man in a white baseball cap can be seen carrying a backpack over his shoulder. “He stops just about in the middle of the frame of the photo and slides that backpack down on the ground and stands there for a period of time,” said DesLauriers. The man then makes a brief cellphone call and hangs up.

Said DesLauriers, “A very short period of time later you hear the first bomb go off at the marathon finish line farther eastward on Boylston Street.”

People in the crowd react with shock to the sudden noise, looking to their left to see what’s going on.

“This individual does not act like that,” said DesLauriers. “He briefly, very quickly glances to the left and then walks to the right very deliberately out of the range of the camera.”

About 15 to 20 seconds later, the second bomb goes off right in front of the camera. "It is a horrifying scene. You see people die," said DesLauriers. "You see people grievously injured, before your eyes."

"When I first saw that video, I couldn't keep a dry eye."

Law enforcement officials had to make a risky decision. Should information be shared with the public, or withheld? Would releasing the photos lead the suspects to flee, or speed their capture? Would it taint evidence or any potential jury pool?

Davis favored releasing the photos in the name of public safety. Officials had already canceled a Boston Celtics basketball game and a Bruins hockey game to deprive the perpetrators of potentially tempting targets.

Not everyone agreed with Davis, however. An argument raged for 24 hours. According to Davis, the hold-up came from Washington.

“I did say that I want the name of the official that said that,” recalled Davis. “Because if something happens … I want to be able to identify who was responsible.”

On Thursday, April 18, the debate was over. At 5:20 p.m., the pictures were released, identified as “Suspect 1” and “Suspect 2.” At Boston Medical Center, Jeff Bauman was watching television when the photos appeared on his screen. He instantly recognized “Suspect 1,” the young man in the black baseball cap and sunglasses.

“I saw him on TV and said, ‘That’s the kid.’”

After the photos were shown to the public another avalanche of tips came pouring in. Authorities had barely begun sifting through the information when police radios crackled at 10:33 p.m.

“Possible person shot. Received call MIT. PD officer down there, use caution.”

Officer Sean Collier had been shot five times and killed as he sat in his patrol car on the Massachusetts Institute of Technology campus in Cambridge.

At the time, with the identity of the assailants unknown, authorities thought the shooting was tied to the armed robbery of a nearby convenience store.

Much later it became clear there was no link between Collier’s murder and the stick-up. But whoever killed Collier had tried to steal his gun -- only to be frustrated by a holster system that held it in place.

Less than an hour later, there was another message broadcast on police frequencies. Officers were asked to be on the lookout for a black Mercedes SUV. Two men had carjacked the vehicle in the Allston neighborhood of Boston and taken the owner hostage.

At 15 minutes after midnight, when the carjackers stopped the SUV at a gas station in Cambridge to buy gas, their captive had escaped. He ran across the street to another gas station and called 911. Later, police would learn that while he was held captive he’d been forced to withdraw $800 at gunpoint, and had watched as his kidnappers transferred unknown objects into the SUV from a green Honda.

Expecting a footrace, not a firefight

The SUV was then tracked via GPS by police. It headed west through Cambridge and into Watertown, a suburb of Boston on the north side of the Charles River about eight miles from the marathon finish line.

Watertown Police Chief Ed Deveau told NBC News that when the call came in from Cambridge, his officers weren’t expecting what followed.

“My officers truly believed they were going to stop that car, two teenage kids were going to jump out of it, and they were going to chase them through the backyards.”

Instead, a quiet residential neighborhood turned into a war zone. A Watertown cop in a patrol car had followed the SUV onto Laurel Street at about 1 a.m. when the vehicle suddenly stopped and the driver stepped out, brandishing a gun.

The driver began walking toward the patrol car and shooting. The officer threw his car into reverse and reported, via radio, “Shots fired!”

A second patrol car showed up, and then the suspects raised the ante. Devices were flung from the SUV toward the police. They exploded.

One of Deveau’s officers told him via radio, “Chief – they’re shooting. They’re throwing bombs at us. And I think these are the guys that killed the MIT officer.”

Deveau said that the average police gunfight lasts just 10 seconds, but his officers were alone for the first few minutes, trying to defend themselves against bullets and bombs, something they’d never seen before.

The police radio began to hiss and crackle again and the Watertown cops weren’t alone much longer. Cars from agencies across metropolitan Boston began to converge on the scene.

The sound of the gun battle awoke residents and turned them into citizen journalists, recording the noise and murky images of the street with smart phone cameras.

For 20 minutes, the cops and the suspects exchanged fire from behind parked cars.

Then, without warning, the SUV’s driver made another move, charging down the street firing a gun.

One of the terrified residents of Watertown watched from his window.

Said Andrew Kitzenberg, “It absolutely felt like it was something from a movie. He was charging them and engaging them in gunfire. As he got closer, maybe about 25 to 30 yards away, that’s when he went down.”

The shooter, who would later be matched to the photo of Suspect 1, had been wounded as he charged at the officer, but kept firing until his gun jammed or was out of ammo. He threw his weapon at the cop, and turned to run. The officer tackled him in the street. A group of officers held the suspect down and cuffed him.

Then Kitzenberg watched from his window as the other suspect got behind the wheel of the SUV. “And that’s when he turned around and started driving, accelerating, towards the Watertown police vehicles.”

As he sped away, the fleeing suspect ran over the body of Suspect 1, his partner in crime. The SUV dragged the body 30 feet.

Suspect 1 would later be declared dead of the combined effect of gunshot wounds and blunt force trauma at a local hospital. But Suspect 2 made his escape, in part because there was an officer down who needed attention, and in part because the thick tangle of police cars made it hard for any vehicle to give chase.

The crush of volunteers from multiple agencies across Massachusetts without any central leader had turned Laurel Street into a circular ambush, where cops were firing at other cops.

“Certainly not a good idea,” said Davis. “They see somebody shooting, so they fire at them. That’s their training.”

Police had fired 200 or more rounds, and while the suspects had exploded a pressure cooker bomb and at least two pipe bombs, only a single gun was found at the scene. Accounts differ, but the suspects may have fired fewer than ten rounds, according to police sources.

Police bullets had pierced fences and trees and a chair inside Andrew Kitzenberg’s house. One bullet had also hit Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority officer Richard Donohue in the groin, and he was bleeding profusely. His ambulance had to weave through the web of police vehicles before it could race to the hospital.

Fourteen other cops were injured during the firefight. None of the injuries were major. None of the officers were hit by bullets from the suspects.

Midnight had come and gone and it was becoming clear that the bombing and carjacking and the murder of Sean Collier were all related, and that one of the men linked to all three incidents was dead. But as Friday dawned, the manhunt wasn’t over.

On Friday morning, Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick ordered a lockdown of Boston and surrounding towns. One million people were ordered to shelter in place. Schools were closed, mass transit stopped.

The suspect who was killed in the firefight, Suspect 1, had been identified from fingerprints taken at the hospital as 26-year-old Tamerlan Tsarnaev, a Russian Muslim immigrant of Chechen ethnicity who’d moved to the U.S. in 2004.

DesLauriers said he was soon told the FBI had conducted an investigation of Tsarnaev back in 2011, and hadn’t found “corroborating information of radicalization.” Congressional investigators now say U.S. authorities were warned by the Russians about Tsarnaev’s background, but missed several chances to detain him as he went to and from the former Soviet Republic of Dagestan, where he apparently trained in jihad.

Read the NBC report on the House Homeland Security Committee investigation of the Boston bombing.

The alleged bomber still on the run, Suspect 2, was identified from tips as Tamerlan’s 19-year-old brother Dzhokhar, a college student. He was the man in the Boylston Street video with the white baseball cap.

At Boston Medical Center, Celeste Corcoran was watching television with her sister Carmen Acabbo, the runner she’d been waiting for at the marathon finish line when the bomb took her legs.

The news that a suspect was loose nearby was hard for Celeste to take. Said Carmen, “The city was under lockdown and I remember being scared. And Celeste just said, like, ‘Turn the TV off,’ like she didn’t even want to see it.”

Meanwhile, authorities were hunkered down in a makeshift command center at a local mall. They’d just gotten a lead that Dzhokhar Tsarnaev might be headed for New York on an Amtrak train.

But officers on the ground continued to search Watertown, believing that Tsarnaev might be wounded and unable to keep moving. Both the SUV and the green Honda had been found abandoned not far from the scene of the Laurel Street shootout.

Starting before sunrise, Chief Joseph Cafarelli and Sgt. James Rose of the Boston area’s North Metro SWAT Team went from house to house in Watertown. They knocked on doors and searched yards into the afternoon without success.

The governor could only keep a whole state locked down for so long, and after consultation with President Obama, Gov. Patrick rescinded the order at 6:07 p.m. Some of the law enforcement teams in Watertown got ready to leave.

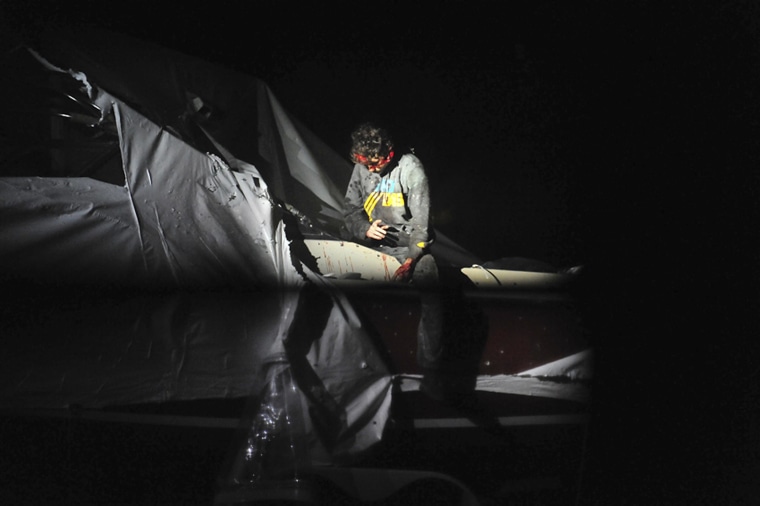

A little later, as afternoon turned to evening, one resident of Watertown’s Franklin Street stepped outside to fix the tarp on his boat, which had somehow come loose while he’d been bottled up in his house.

He fixed the tarp and went back inside. But then he decided to take another look, since he wasn’t sure why the cover, which he’d attached tightly, had come loose. He put a ladder up to the side of the boat, and looked underneath the tarp.

He saw blood, and then more blood. And then he saw a man, lying next to the engine block. He hurried back down the ladder and into the house and called 911.

“We had just finished searching the last residents on the last street of our area of operation,” recalled Chief Cafarelli.

Officers from the Boston PD, Watertown PD, tactical units and the state police surrounded the boat, waiting for any sign of movement.

At around 7 p.m., the police radio buzzed with a warning. “There’s a perp in the boat trying to poke a hole in the liner, a perp in the boat. Live party who may be trying to toss an object out, live party in the boat confirmed.”

The man inside the boat was sticking some kind of long, thin object up through the tarp.

A sniper on a nearby roof saw the object – which later turned out to be a fishing gaff -- and fired at the boat. The officers around the craft began shooting at the craft, riddling it with bullet holes. After ten seconds, they heeded a commanding officer’s order to hold their fire.

The North Metro SWAT unit arrived on scene and took up positions. Just before 8 p.m., the FBI deployed a robotic arm to pull the tarp off the boat, and then used flash grenades and bullhorns to force the suspect out.

After the second assault, thermal images from a state police chopper up above confirmed that the man in the boat was still moving. Meaning that he was alive and, presumably, armed and dangerous.

The suspect came out from under the tarp, his hands up.

Dzhokhar Tsarnaev was lit up like a Christmas tree with laser sights, as photos later released by the Massachusetts State Police to a local magazine showed. Red dots appeared all over his body as SWAT Team members took aim, their safeties off.

Sgt. Rose said he tried to keep himself calm and collected, but his heart was “pounding out of his chest.”

Cafarelli said he was thinking, “Don’t screw up, don’t screw up.” He was also thinking about Martin Richard, the 8-year-old killed by the bombing, and his own young son, who he said was the “spitting image” of the victim. He thought about how just a few rounds from any one of the heavily armed men surrounding Tsarnaev could end the drama, and bring a form of closure to the events of the past four days.

“It wouldn’t have fixed anything,” he said. “We’re professionals. We’re law enforcement. We’re not an execution team.”

Instead, three or four SWAT Team members grabbed Tsarnaev and laid him on the grass. They met no resistance as they handcuffed him and placed him into custody.

Tsarnaev was wounded and losing blood. There was no weapon on his body or in the boat.

Rose alerted the command center by radio. “North Metro SWAT to command. Suspect in custody.” It was 8:42 p.m., 108 hours after the start of the marathon.

A wave of relief spread over Massachusetts. For a small group of professionals, however, the work was just beginning. Tsarnaev was rushed by ambulance to Boston’s Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital with multiple gunshot wounds.

A nurse who asked NBC to identify her only by the pseudonym "Kate" said she walked in the door at the ER and was told, “You’re going upstairs,” and she knew right away what it meant. She would be working on the bombing suspect.

She went into nurse mode. “That part was very easy,” she said. “You just did what you always do. But when you walked out of the room, the reality of the situation would hit you.”

Kate said she felt guilty helping someone who had allegedly hurt so many people, but was ultimately glad she’d done her job. “I’m really proud that all of us did a good job.”

A respiratory therapist, who asked that NBC call him “Larrs,” is also proud that he was able to put his feelings aside and do his job, as he said he’d learned in the military.

“And we did it well,” he concluded. “Because he’s ready to stand trial.”

Tsarnaev, now 20, faces multiple terrorism charges and could receive a death sentence if convicted. Some of his caregivers, who restored him to health, may be called to testify at his trial.

A year later, Ed Davis, now retired from the Boston Police Department, says his city will never be the same.

“As far as people’s feeling of community here, and their feeling for their neighbors,” said Davis, “this tragedy had an incredibly powerful and positive effect on this community.”

The past year has been challenging for the bombing victims. Celeste Corcoran, who has learned to walk, drive and even run on prosthetic legs, said she thinks of it as a grieving process. Some days she feels positive. “There are other times where [I] think I’ll never stop crying for what we’ve gone through and almost lost.”

Her daughter Sydney, who was able to keep her leg, said she struggles with post-traumatic stress. She became a prom queen and then started college, but there are days when she’ll be watching a movie and break down. Said Sydney, “I just start sobbing. It’s like I don’t even realize that I was going to have that reaction.”

Jeff Bauman is engaged to Erin, the girlfriend he’d gone to watch at the marathon last April. They are expecting their first child. His memoir, “Stronger,” came out this week.

Bauman says he wants his experience with prosthetic legs to help researchers improve them.

“I think that’s what I want to do in the future,” said Bauman. “Just keep pumping out new technology.”

Celeste Corcoran returned to Boylston Street, the site of the bombing, for the first time in March. She had her picture taken. It was a freezing cold day. She sat down on the seal in the pavement that marks the finish line of the marathon. She took off her prosthetic legs and laid them in front of her.

“On my naked, scarred legs,” she said, “I wrote the words, ‘Still Standing.’”