Donald Trump was quick Friday morning to link Britain’s stunning vote to leave the European Union — which he called “a great thing" — to his own crusade for the White House.

“They took their country back, just like we will take America back,” Trump tweeted.

It’s not such a stretch. The “Leave” campaign drew strength from many of the same fears about open borders and unaccountable global elites that have powered the Trump phenomenon. And, no surprise, its voters look notably similar to his.

But in predicting what the "Brexit" vote might mean for our own politics, we should be careful about drawing parallels that are too direct.

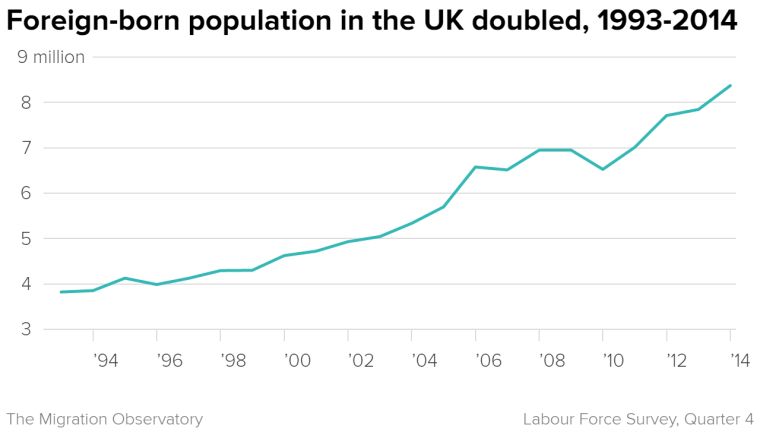

As the campaign wore on, “Leave” supporters increasingly sought to turn it into a referendum on immigration from Eastern Europe and beyond. The notion that Turkey might soon gain EU membership, leading to a new flood of Muslim immigrants, was a top talking point.

Nigel Farage, the leader of the far-right U.K. Independence Party and a key Brexit advocate, last week unveiled a billboard showing a teeming mass of dark-skinned men lined up as if ready to cross the English Channel, next to the words “Breaking Point.” Never mind that the photo actually showed Middle Eastern migrants crossing the Croatia-Slovenia border last year. The point — that sticking with the E.U. meant in letting in people who aren’t like us — came through loud and clear.

As if to prove the point, the French far-right leader, Marine Le Pen, who has made her career on attacking Muslim immigration, changed her Twitter picture to a Union Jack and wrote: “Victory for Liberty.”

Appeals like this, of course, would also seem right at home in Trump’s campaign, which was launched with a speech about how Mexican immigrants are rapists, and which went on to advocate an outright ban on Muslims entering the country. Polling data suggest Trump’s supporters are more likely than other Americans to hold views that might reasonably be described as anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim, and racist.

Trump himself drew the connection at a press conference Friday morning in Scotland, where he’d gone to promote his golf course.

Related: Britain's Brexit: How Baby Boomers Defeated Millennials in Historic Vote

“You're taking your country back,” he said of the vote. “You're going to let people that you want into your country, and people that you don't want, or people that you don't think are going to be appropriate for your country, or good for your country, you're not going to have to take.”

Related: Brexit Backlash: Dow Falls 500 Points as Markets React

Brexit’s and Trump’s backers appear to look similar, too. The older British voters were, the more likely they were to choose “Leave,” exit (Brexit?) polls suggest. Among those older than 65, six in 10 voted to get out. Brexit ran stronger among whites, too, than among racial minorities. And perhaps the single most effective predictor of whether someone voted for Brexit was their educational status: 57 percent of those with university degrees opted to stay, while a large majority of those who didn’t attend university voted to leave.

Trump’s supporters, too, are disproportionately older and white. And though, thanks mostly to the racial skew, they’re actually more likely than most Americans to have a college degree, Trump does better with whites who didn’t go to college than whites who did. Not for nothing did Trump declare: “I love the poorly educated.”

Then there’s the issue of the revolt against elites. Among the European Union’s perhaps fatal weaknesses has long been the sense among many of its citizens that it’s run by distant bureaucrats who are only very loosely accountable to ordinary people. Turnout for European elections is low, and almost no one knows the identity of their E.U. representative. Voting “Leave,” it was said, would strike a blow in favor of self-government and national sovereignty.

In the U.S., Trump has played on some of the same concerns. He has painted Hillary Clinton as a tool of global economic forces who don’t have America’s best interests at heart. He has leveled a broad attack on the political establishment of both parties, portraying conventional politicians as self-interested and out of touch. Even Trump’s disdain for “political correctness” is about thumbing his nose at elite standards of discourse, which are seen as mealy-mouthed and evasive. “Come November, the American people … will have the chance to reject today’s rule by global elite,” Trump declared in a statement Friday.

Despite all this, we shouldn’t take the comparison too far.

Related: Trump Takes a Surreal Victory Lap in Scotland

For one thing, Britain’s E.U. membership really did mean an open borders policy, at least in relation to other E.U. members. Trump’s rhetoric aside, that’s not at all the situation in the U.S. — perhaps one reason why polls suggest that, outside of Trump’s nativist base, most Americans have relatively positive feelings about immigration.

The same point applies more broadly. British voters, like plenty of others in Europe, have for several years been deeply angry over a financial crisis that was followed by needless and harmful austerity policies, dramatically reducing faith in the major political parties. It’s not quite the same here. For all the pixels spilled this U.S. primary season about the angry mood of an electorate threatened by economic dislocation and cultural change, President Obama is popular and getting more so. The economy is growing — even if its benefits aren’t being shared widely enough — and joblessness is low.

A big part of this is demographics. No breakdown of the racial makeup of Thursday’s election appears to exist, but Britain’s population is about 85 percent white. By contrast, non-whites in the U.S. are expected to make up nearly 30 percent of voters this fall. That means that appeals to nativism here have a much steeper hill to climb — as Trump’s weak poll numbers appear to show.

Of course, perhaps the one thing most likely to raise those numbers and boost Trump’s chances of winning the White House would be a global recession. And that’s just what many economists fear could happen thanks to Thursday’s vote, which already has had a seismic impact on financial markets.

While in Scotland to promote his golf course on Friday, Trump even suggested that the declining British pound would be good for business, his properties included.

"If the pound goes down, they're going to do more business," he said.

In that sense and a larger one, Brexit and Trump really could go hand in hand.