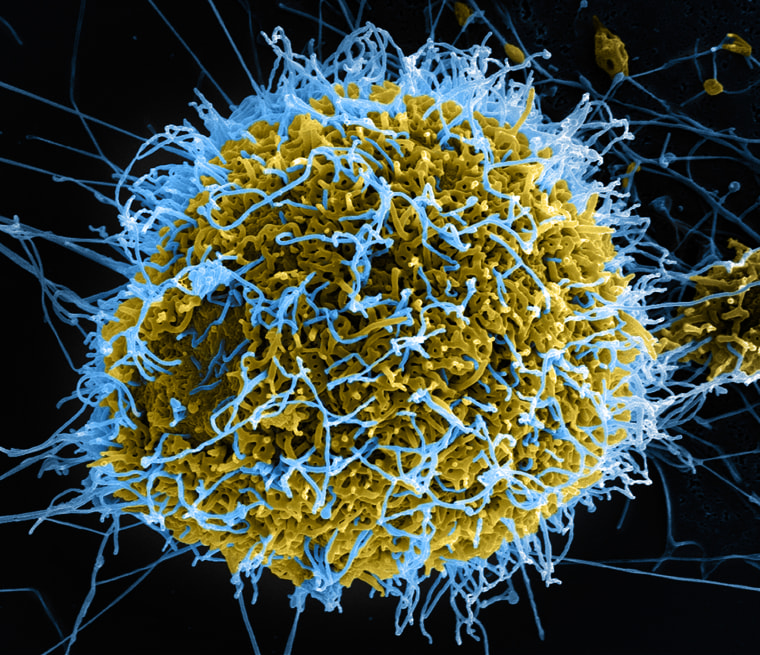

The Ebola virus mutated early on in the 2013-2016 West African epidemic, taking on a simple change that made it infect human cells more easily, researchers reported Thursday.

Two separate studies point to the same change — a single mutation in the part of the virus that helps it infect cells.

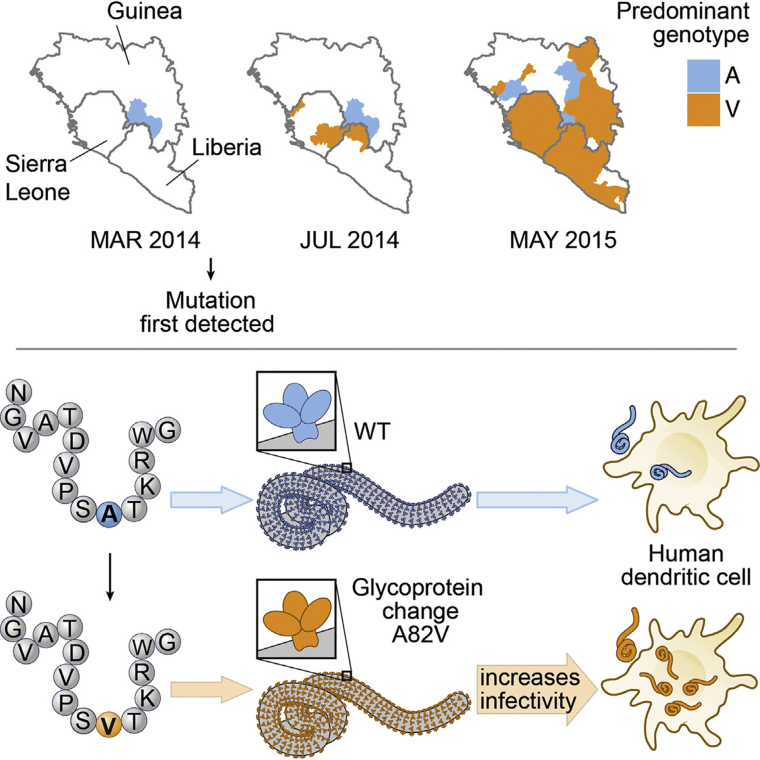

After this change, which happened very early in the epidemic, the mutant virus swept out of Guinea, across Liberia and Sierra Leone, and was carried by travelers to Nigeria, Mali and a hospital in Dallas, Texas.

“It had never been seen before and it persisted,” Jeremy Luban of the University of Massachusetts Medical School, who helped discover the mutation, told NBC News.

“Pretty much from that point out, it never went away. Every version observed after that had that mutation. It is also the virus that traveled not just to Sierra Leone and Liberia — even to an emergency room in Texas.”

“Pretty much from that point out, it never went away."

The Ebola epidemic started in Guinea, and by the time it died down earlier this year it had infected more than 28,000 people and killed more than 11,000 of them. It devastated the already struggling economies of Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea.

Related: Full NBC Coverage of the Ebola Virus Outbreak

Carried in bodily fluids including blood, sweat and the diarrhea suffered by patients, the virus killed a disproportionate number of health workers, and infected several U.S. doctors and volunteers.

One patient carried the virus to a Dallas hospital, where he died, but not before two American nurses who cared for him were infected.

Previous outbreaks had been small and limited, and doctors wondered whether the virus had changed.

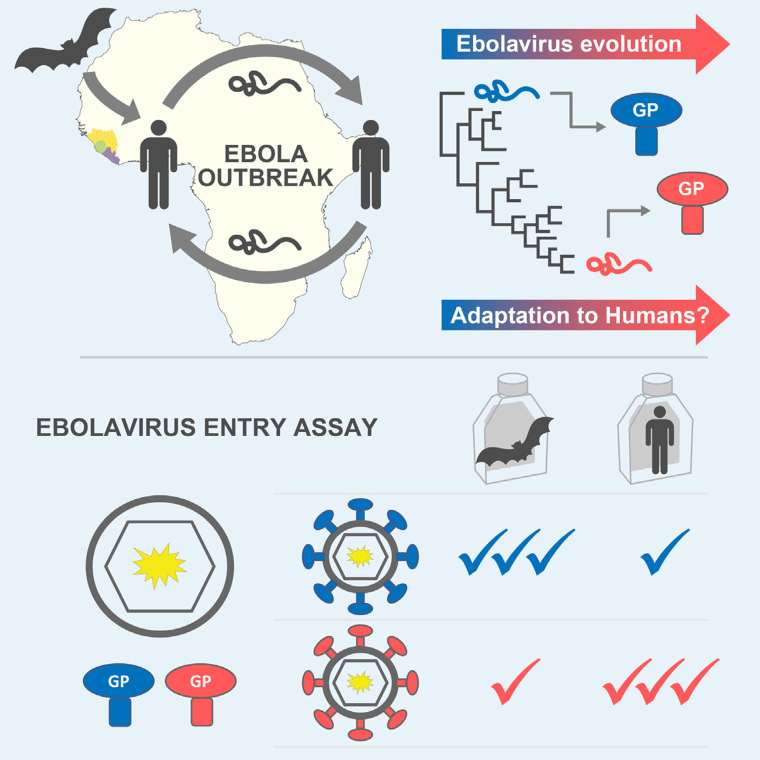

It had. Jonathan Ball of Britain’s University of Nottingham and colleagues deliberately searched through samples of the virus to see if they could find mutations, and did. The mutation is called A82V and it’s a subtle change, they reported in the journal Cell.

"It is the tip of the protein that inserts into the lock that allows the virus to enter human cells," Luban said.

They generated non-infectious bits of virus and tested them in living cells to see if the mutation made a difference. “The A82V substitution alone resulted in an almost two-fold increase in infectivity in human cells,” they wrote.

Luban discovered the same mutation separately and entirely by accident. His team was working with HIV, the human immunodeficiency virus that causes AIDS. He had been looking for what are called host factors — differences in human cells that make it harder or easier for viruses to infect them.

The team used a standard technique, swapping in bits of other viruses, including Ebola. Like Ball’s team, they did not work with living, infectious viruses, but harmless pieces tacked onto cassettes of genetic material called plasmids.

Related: Ebola Comes Back Hours After Outbreak Declared Over

They noticed some of the Ebola virus proteins were more infectious than others.

“I would say it was almost an accident,” Luban said. “We were studying something and we stumbled upon this discovery.”

Luban contacted Pardis Sabeti at Harvard University and the Broad Institute at Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Sabeti is an expert on the genetics of infectious diseases, including Ebola.

“It was the first time I ever met Pardis and she was jumping up and down,” Luban said.

“I had been trying to get people to do this,” said Sabeti.

“The more time you give it to change the more chance it will."

The teams tested the various strains of Ebola in lab dishes and found the same thing Ball’s team found — the mutation made it infect human cells more easily, and made it less able to infect the cells of other animals, such as bats.

It’s too soon to say if that means the virus actually transmitted more easily from one person to another, or if it made infections worse in people, both teams of researchers say.

“Despite the experimental data provided here, it is impossible to clearly establish whether the adaptive mutations observed were in part responsible for the extended duration of the 2013–2016 epidemic,” Ball’s team wrote.

They agree with other experts who say many factors helped make this epidemic thousands of time worse than previous outbreaks: the urban setting, the large movements of people from one country to another, the almost complete lack of health care in the three worst-hit countries and a mistrust of officials and doctors trying to help.

“As long as there are countries that do not have proper health systems, everyone in the world is vulnerable.”

And Sabeti says the world’s slow action to contain the epidemic helped the mutation arise in the first place.

“The more time you give it to change the more chance it will,” she says. “We are giving the virus many opportunities to replicate and to pass form human to human. And each of those is an opportunity for an accidental mutation to allow it to adapt.”

Lina Moses of Tulane University says poverty and a lack of any organized health care system allowed the epidemic to happen.

“If Sierra Leone had the health system and the health infrastructure that we have in the U.S. you would have seen two cases like we saw in the U.S., instead of thousands and thousands of cases like we saw here,” she says in a video released by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

“As long as there are countries that do not have proper health systems, everyone in the world is vulnerable.”

Is the mutant version still around? Luban says it's not clear. The virus's adaptation makes it more easily infect not only human cells, but those of other primates such as apes. And Ebola's been found to linger in bodily spaces such as semen and in the eye.