KINSHASA, Congo — The Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo appears to be under control, although the virus can always surprise, World Health Organization officials said this week.

Around 1,000 people who have been in contact with Ebola patients have been vaccinated and health workers are working to get vaccine to more remote affected parts of this giant, central African country.

And they are working to get the word out to people in city and country alike about Ebola, which has never affected this particular part of Congo before.

It has not been easy, and not only because the region lacks roads, electricity or telecommunications.

"These are communities that often deal with many other illnesses, so why is the world suddenly paying attention, coming to their villages to see them,” said Mari Nythun Sorlien, an anthropologist working for Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF or Doctors Without Borders).

"This outbreak has been particularly difficult because we've had a lot cases. Some people have lost multiple family members, so there’s a lot of drama and worry," she added.

WHO, MSF and other groups have learned to take a gentle approach, even as they feel pressed to quickly educate people about the risks of Ebola, whose symptoms can resemble those of a half-dozen common tropical illnesses such as malaria.

Patients with suspected Ebola must be isolated as soon as possible, and anyone coming into close contact should be protected with layers of gear. The virus is passed in bodily fluids such as blood, feces and sweat – all of which can be on the bodies of patients suffering from the virus.

Anywhere between 50 percent and 90 percent of people who become infected with Ebola will die.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo's (DRC) health ministry says there have been 38 cases in this outbreak, with 13 deaths.

Getting people to change their habits and valued practices takes tact and patience. But it's a matter of life and death, because Ebola virus can be transmitted even after death, unlike many other diseases.

Burials must be sterile, the bodies wrapped tight. That can go against the grain in communities where sick patients are usually lovingly tended closely, and where the dead are carefully washed and dressed before burial.

"It's a human reaction. In every culture, whatever your social background, it’s very difficult for someone to be isolated from their loved one whether they are sick or deceased," said Sorlien. "Most important for me is to give a role to the family — letting them know they can come and visit the treatment center to see their loved ones from a safe distance."

Health workers learned from their mistakes during the 2014-2016 Ebola epidemic in West Africa, in which 28,000 people were infected and 11,000 died. There, they often lost the trust of communities when strangers stormed in and demanded they hand over their sick and dying.

“Before, our approach was top-down and much more medical. This time we made a decision to use a different approach and use community participation,” said Raoul Kamanda Mangamfu, a spokesman for the DRC’s health ministry.

Ebola was first identified in the DRC, in 1976, when the country was called Zaire. This is the country’s ninth outbreak, but the first in this particular part of the country.

And it’s the first to show up in a city in DRC – in Mbandaka, a city of 1 million that sits on the Congo River. It’s also been seen in the nearby community of Bikoro.

People in this area are not used to hearing about Ebola. And they are not used to taking orders.

“Here in Bikoro people like to debate. They don’t accept messages as they come, so we spend a lot time explaining where the virus is and how it is transmitted,” Sorlien told NBC News.

“What works best are community events, Q&As and discussions. People here like going deep into the issues, which is helpful for us to understand what they are integrating.”

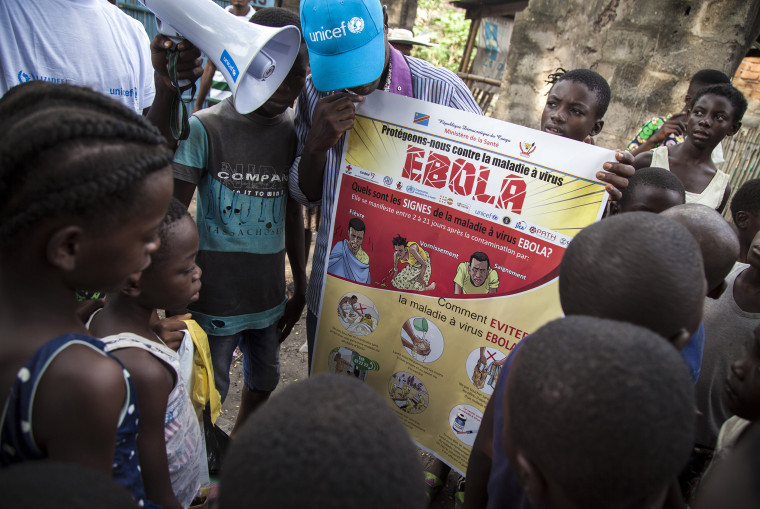

So trained educators are going door to door, visiting people in their homes. They are calling meetings, and using materials they know will work. When possible, people who speak local dialects are employed.

“We try using concrete examples and we show them very simple drawings, which are especially helpful with children,” said Sorlien, who is working on her fifth Ebola outbreak.

Respect is also important.

"When we investigate a case, see a patient, our teams are required to ask permission to ask questions," said WHO representative Dr. Franck Mboussou. "Usually it works, and then we ask the patient where they've been and who he/she has been in contact with."

It’s important to track down every patient, and then find everyone that patient has been in contact with. WHO is employing a technique called ring vaccination, in which anyone who has been with or near an Ebola patient gets immunized, and then all of their contacts are also tracked down and vaccinated.

It’s tedious, and requires trust.

"People are often worried about side effects, that they’ll have to stop working, and so we reassure them,” Mboussou said.

"We also work with important people in the community, from women’s associations or local elected officials for example, and we make sure they accompany us in the field,” said Chiran Livera, who leads the International Federation of the Red Cross Ebola response in DRC.

As in Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea, one of the hardest negotiations is over the funeral. A dozen or more people can get infected with Ebola during the preparation for a traditional burial.

"The most difficult for our outreach teams are the burials,” said Mboussou.

They’ve found it’s often easier to just bury everyone who dies in the safest possible way, to avoid stigmatizing Ebola victims and their families.

“Our teams are trained in negotiation and the most important message we always give is that we don’t say their family member died of Ebola — but we explain to them that in a time of Ebola outbreak it is better for the entire community to take precautions," Mboussou said.

Some people were reluctant to believe that a virus was causing the deaths and illnesses.

“A majority of people thought it was a masquerade,” Joseph Zambo, a resident of Mbandaka and father of two. “For example, people who go to certain churches are told the virus is a demon that needs to be chased as the Bible requires.”

But Zambo said he was convinced by the outreach teams. “In our family, we’ve made it a habit at home to wash our hands with chlorine,” he said. And he said most people now understood the need for hand hygiene.

“We also use dispensers at the office and when we go to church,” Zambo said. "This is a major logistical and boots-on-the-ground epidemiological endeavor now," Peter Salama, WHO’s Deputy Director-General for Emergency Preparedness and Response, told a news conference in Geneva on Friday.

"Phase one, to protect urban centers and towns, has gone well and we can be cautiously optimistic,” Salama said.

Reporting by Louise Dewast in Kinshasa. Additional reporting and writing by Maggie Fox in Washington.