There’s one thing that both anti-abortion and abortion-rights activists agree on. A shift is underway in Europe — in politics, prosecution and protest. Battle lines are drawn for what threatens to be a nasty fight, with both sides taking cues from the U.S. In Part One of a series, NBC News examines the debate.

***

Remember Donald Trump’s suggestion that women be punished for abortions? Across the Atlantic it isn't just a throwaway suggestion from a politician. It's now a reality in a corner of the U.K. — and a chilling reminder to one woman.

"It could’ve happened to me," K. says.

Life Imprisonment

The act that made abortion legal in England, Scotland and Wales for women up to 24 weeks pregnant does not apply to another part of the U.K. — Northern Ireland.

That means that there is a near-total ban on abortion there, even in cases of rape, incest or fetal abnormalities. Terminations only are allowed under strict criteria: if the pregnancy threatens the mother’s life or would adversely affect her mental health.

Courts in Northern Ireland can inflict the harshest criminal penalties for abortion of anywhere in Europe — up to life imprisonment.

That’s how it came to pass that a 21-year-old woman was convicted this month of having an abortion. She was given a three-month suspended sentence.

Europe's Abortion Fight: Women Share Their Stories

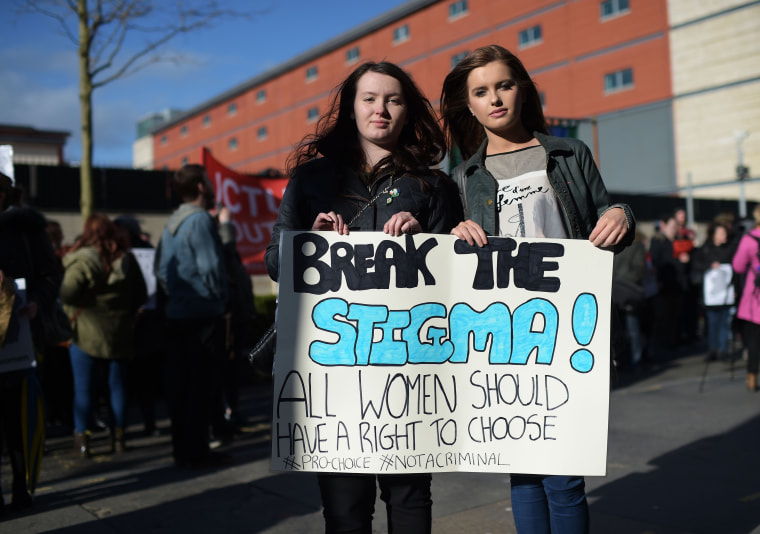

The case sent shockwaves throughout Europe, sparking protests and the solidarity movements behind the hashtag #NotACriminal. On Wednesday, a mother accused of procuring abortion pills for her teenage daughter is also due to go on trial.

Most of Europe offers easy access to abortion — but a handful of countries that don't have almost simultaneously been thrust into the spotlight.

"There's an assault on women's rights really across the world at the minute,” says Goretti Horgan, a Northern Ireland-based pro-abortion activist and university lecturer.

The convicted woman told the court she had tried to travel to England for an abortion, but just didn’t have the money so she ordered pills online.

Her story rang eerily familiar to K. — who said one different decision could have led her to the same outcome.

'It Was Just the Wrong Time'

When K. found out she was pregnant at the end of 2014, the mother-of-two decided she wanted to get an abortion.

"At that time my youngest was born and he'd only just started sleeping through," the 27-year-old said. She also was still grappling with post-natal depression and trying to get her eldest son, who has special needs, into preschool.

"I was in a very fragile place," she said. "When everything was settling and getting back to normal, another baby would've just upset everything ... It was just the wrong time.”

"I was thinking ... whether I could throw myself down the stairs just enough to not hurt myself but to end the pregnancy"

K. knew she wanted to get an abortion, but ending her pregnancy was from easy.

She came across an online service that ships abortion pills around the world but feared prosecution if anything went wrong and she needed to see a doctor.

“I was just worried that they would report me to the police if they suspected that I had had an abortion," she said. "I was worried that they’d find some reason to take my children away.”

"I turned into a zombie, I couldn't get out of bed,” she added, recalling her despair at trying to find a solution.

K. decided to fly to the English city of Liverpool — "traveling was the least worst option" — but covering the cost was a huge strain for the student and her husband.

"We were just kind of panicking and working out ways to cut our bills and try to make the money up for it," she explained.

She house-sat so her family could piggyback off food and utilities but the “worst thing” was having to withdraw her eldest from pre-school — they’d enrolled him early due to his speech problems.

But the scrimping and saving didn’t come up with enough money for the procedure, only the flight.

Finding a way to end the pregnancy without spending money consumed her.

"It was all I could think about," she explained. "I was still on anti-depressants from my post-natal depression — I was thinking how many of those could I take to end the pregnancy without doing permanent damage, whether I could throw myself down the stairs just enough to not hurt myself but to end the pregnancy."

"There's no reason why I should have been that desperate," she added.

Mingling Accents

Northern Ireland’s strict abortion laws prompt thousands of women each year to travel to England in order to procure a termination.

K.'s desperation over the cost was due to another geographical anomaly: Women living in other parts of the U.K. can receive abortions for free under public healthcare, but that doesn’t apply to the Northern Irish. They have to pay.

Abortion providers like the Marie Stopes Clinics and the British Pregnancy Advisory Service offer discounted prices for women like K. — but note that doesn’t address the larger issue.

“We’re proud and pleased to be able to help women where we can but ultimately these women deserve services at home,” said Clare Murphy, director of external affairs for the British Pregnancy Advisory Service.

In the absence of legislative change, abortion clinics’ waiting rooms in England echo with Northern Irish tones — but they mingle with the brogues of the nation to the south. One hospital's waiting room has even become nicknamed "The Shamrock Suite."

Tragedy and Outrage

A sorrowful sisterhood has been born between women from Northern Ireland — which is part of the U.K. — and the neighboring Irish Republic. Women there have long been grappling with legal barriers of their own.

“There isn’t really a difference between Northern Ireland and the republic — there's different legal systems but the effect is the same,” Horgan said. “The effect is that you can’t get an abortion except maybe to save your life.”

Abortion was outlawed in the Irish Republic until 2013, when the death of a young woman named Savita Halappanavar prompted a slight relaxation of the ban.

Halappanavar, a 31-year-old dentist, died from septic shock at an Irish hospital after being denied an abortion though doctors agreed she was miscarrying at 17 weeks.

Outrage over her death — decried by womens' groups and activists as preventable — led the Irish Republic to adopt an exception to its abortion ban, allowing terminations if the pregnancy poses a “real and substantial risk” to a woman’s life.

The provision takes into account the risk of suicide, but healthcare professionals say the criteria is poorly defined.

The punishment for procuring an abortion in the Irish Republic, or helping someone to do so, is a fine or up to 14 years in prison. There are also restrictions on providing information about abortion services.

That’s why Irish women, too, have been going to great lengths to get abortions — trying to obtain pills online or joining in the maternity migration and looking abroad for the procedures.

More than 5,520 of the over 190,000 abortions recorded in 2014 in England and Wales were given to women who listed addresses outside of those countries — 15 percent of whom gave addresses in Northern Ireland and 68 percent in the Irish Republic, according to the most recent figures from the U.K. Office of National Statistics.

At least 10 a day entered the U.K. from the Irish Republic to access abortion services in 2014, according to the Irish Family Planning Association. They were among the 163,514 Irish women to seek abortions abroad between between January 1980 and December 2014.

'My Dead Baby'

Julie O’Donnell was one of them.

The restaurant manager was “over the moon” when she found out she was pregnant. Her young son Ben “desperately wanted a little brother and sister.”

The six-year-old was there when O’Donnell went in for her scan — and picked up on the mood in the room when the technician went quiet. Instead of being able to celebrate over whether she was having a boy or girl, O’Donnell found herself in her “worst nightmare.”

The baby had anencephaly; it was missing a major portion of its skull.

“Zero chance of survival,” she told NBC News.

O'Donnell said she knew almost immediately there was “no way” she could carry on with the pregnancy only to watch her baby die.

“People congratulating you, coming up to rub your belly, 'When are you due?' ... Mentally and emotionally it was not something I was prepared to do,” she explained.

But when O'Donnell told the doctors, they said their hands were tied by the Irish Republic's abortion laws.

Like K. she flew to Liverpool where she was given an injection that stopped the baby’s heartbeat, then endured a daylong wait.

"We had to go out and eat in restaurants. People are drinking wine and laughing around you and you’re going, 'OK ... I’m going to go in and deliver my dead baby tomorrow,'" she said through tears. About 24 hours later, the hospital induced labor. Baby Aidan was born at around 9:30 that night.

Court Ruling Ignored

The U.N. says that countries with restrictive abortion laws have “much higher” levels of maternal mortality.

Numerous human-rights organizations that say not giving women like O’Donnell the freedom to terminate a pregnancy violates their rights.

U.N. Treaty Monitoring Bodies have found that women should have access to abortion at a minimum when their life or health is at risk, they are pregnant as a result of rape, or there is a diagnosis of fatal or severe fetal impairment.

Belfast’s High Court ruled in December that Northern Ireland’s restrictive abortion laws violated human rights because they failed to provide exceptions for cases of fatal fetal abnormalities or sexual crimes.

Despite that landmark ruling, Northern Ireland's legislature in February voted against relaxing the strict abortion legislation.

The Irish Republic, too, has been criticized by the U.N. Human Rights Committee for failing to make the exceptions. More than 30,000 people have signed a petition by rights group Amnesty International urging reform of the “draconian abortion laws” that criminalize women seeking terminations even in cases of fatal fetal abnormalities and rape.

Trump Makes Waves

Any changes will come too late for the young woman in Northern Ireland who was convicted. Her lawyer has said she was being persecuted for being poor and unable to travel abroad for an abortion. The woman, who for legal reasons has not been named, bought abortion pills online and took them in July 2014 when she was aged 19.

Almost two years later, she reportedly pleaded guilty to two charges — procuring her own abortion by using a poison, and of supplying a poison with intent to procure a miscarriage.

The case due before the courts on Wednesday involves a mother accused of acquiring abortion pills for her daughter. Northern Ireland’s prosecutors declined to answer questions about the details of either case but said they met the required test for prosecution.

The parallels between Trump’s recent comments about criminalization — which garnered headlines worldwide — are not lost on activists in the Irish Republic as well as Northern Ireland and the rest of the U.K.

The GOP presidential candidate later retracted his suggestion that “there has to be some form of punishment” for women having abortions if they were banned.

“Everybody quite rightly held their hands up in horror at Trump and then we have to say, 'Yes, but look — look what's happening here on our doorstep — in part of the U.K.!'” sputtered a red-faced Judith Orr following a panel on abortion-rights panel in London.

“When it's something far away and it's a maverick reactionary like Trump, people denounce him but... It's almost like it’s swept under the carpet here, an embarrassing anomaly,” the activist said.

“We should be shouting from the rooftops the fact that women in Northern Ireland can’t access abortion,” added Orr, who is originally from there. “They pay the same taxes... And yet they don't have the same rights [as women elsewhere in the U.K.].”

The grounds for the recent prosecution date back to 1861 — before the lightbulb was invented or before women had the vote, Horgan notes. She said the 21-year-old woman's case sends a chilling message both to doctors and pregnant women.

“All she did was swallow a pill,” Horgan added. “How can you criminalize somebody for swallowing a pill?”

Ashes by Courier

There used to be a bit more wiggle room when it came to getting an abortion in Northern Ireland. Whether due to sympathetic doctors, contacts or money, women used to be able to find abortion services even if they didn’t strictly conform to the letter of the law.

Gaye Edwards was so excited to see her positive pregnancy test that she started looking at nurseries and car seats early on. But when a 20-week scan revealed anencephaly Edwards said she was “struck dumb.”

Her doctor in Irish republic's capital of Dublin referred her to another across the border in Belfast, Northern Ireland — who then referred her on to an obstetrician who agreed to terminate her pregnancy.

“When I asked him if it was possible that we could just end this, and he said, 'yes,' that he would look after us,” Edwards recalled.

The doctor induced Edwards, who gave birth to a baby boy. They named him Joshua and the hospital chaplain said a prayer. Edwards said leaving her son behind was the hardest part — his ashes were later delivered in a small box to her home by a commercial courier company.

“That was 15 years ago,” Edwards said. “I know of another case of an Irish woman who went up there about 13 years ago but she was either the last or one of the very last to be taken care of.”

Activists say the clampdown came after doctors started receiving official warnings of the potential for life imprisonment.

'I Just Felt Free'

K. takes care to stress that while her abortion story didn't involve a threat to her health, that didn’t make her desperation to get to Liverpool any less real.

She said she found an option that would help cover the cost of the procedure “just in time” — before she did anything “stupid.”

She got news that all about around £100 of the £415 (nearly $600) procedure would be covered on New Year’s Eve, recalling how “the most amazing relief” swept over her.

"It just felt like this huge weight was lifted," she said.

She booked her flight to Liverpool and waited, trying to keep panic at bay over whether she’d misjudged her gestation. That would drive up the cost of the procedure.

A cab picked her up from her rural village before dawn and brought her to the airport, alone. Her partner needed to stay at home with their children, the eldest of whom was about two weeks shy of his birthday.

She recalls wondering whether airport staff would recognize her on her return flight later that day and suspect her reasons for flying to Liverpool. As she waited for her 8:20 a.m. departure she couldn’t eat — not that she’d had much appetite while sick with worry over the previous weeks.

"I just there in silence, watching the clock," she said. "I kept looking at my phone ... trying to block out everything."

When she landed in Liverpool she hailed a cab to go to the BPAS clinic, which performs abortions.

"I thought the taxi driver would be judging me ... He must've known," K. said.

The facility “didn't feel like a hospital" — there were couches and plants, no sign of the "horrible hospital colors" like peach and green, K. said. There were other women also waiting for abortions but they mostly sat in silence.

K. said she was prepared to defend her reasons for wanting the abortion — but was pleasantly surprised when the intake nurse simply said: "Your family's complete, yeah?"

"I felt like crying because she was just so wonderful and accepting," K. explained.

There was a scan, a blood test and eventually K. was brought to a changing area where along with two or three other women she put on a T-shirt — hers, a dark green one belonging to her boyfriend that she’d brought with her for the procedure.

Then she was led into the surgical room.

"I think they could tell that I was nervous and they just told me to count back from 10," K. said.

That’s all she remembers before waking up in the recovery room. The other women in T-shirts were there too — and K. said she was flooded with relief “that it was over.”

The relief followed her to the airport, where she arrived five hours early for her 7:45 p.m. return flight to Northern Ireland. The extra time didn't bother her — K. was happy to wander around the terminal.

"I hadn't eaten properly in weeks with all the worry and I ordered a Subway," she said. "It was the nicest thing I'd ever eaten. I just felt free.”

But that feeling eventually wore off — and was replaced with anger.

"It felt so unfair. All of it ... the secrecy, the having to pay for it ... It just felt wrong," she said. "Something that could've been so simple was just dragged out beyond belief.”

News of the 21-year-old's prosecution in Northern Ireland has left her disgusted.

"She was at the same stage I was ... about 11 weeks along," she said. "Just a few different decisions and telling the wrong people ... She should be able to get the same procedure that every other woman in the U.K. can get."

K. added: “If I’d told someone other than my partner, if I’d gone down the route of taking the pills, it could’ve happened to me. I could’ve been facing prosecution.”

Bleach, Heroin, Gin

In the absence of legislative change, independent organizations have stepped in to try making up the difference.

The Abortion Support Network — which helped K. travel to England — is one of them.

Led by American Mara Clarke — with the help of around 60 volunteers — it helps fund travel for abortions; last year the grants ranged from £27 to £1,500 ($38.32 to $2,129).

“It’s 2016 and not 1950 ... You can Google ways to self-abort”

“All of our client cases are difficult,” Clarke said.

One woman said she drank bleach. Another threw herself down the stairs. One downed three packs of birth control with a bottle of gin, and there was a non-drug user who went out to score heroin in hopes it would help her miscarry.

Clarke has heard all of the above from women seeking her assistance. She’s also heard a less horrific but no-less important reason: It’s just not my time.

“Having a baby is a really big deal. Being a parent is a big deal,” she said. “It’s 2016 and not 1950 ... You can Google ways to self-abort.”

There are women with fatal fetal anomalies, refugees, wives trapped in abusive relationships. Girls under the age of 16, victims of rape, victims of incest.

Some women simply need cab fare, others help covering flights or the cost of the procedure. Some simply need information — where to go, how much it’ll cost, what their options are.

Not every case, though, can be solved.

“Unfortunately we have a number of clients who come over and are too far along,” Clarke added. “They’re pushed into later gestation as they’re trying to raise the money.”

The numbers of women seeking ASN’s assistance have been steadily climbing — from four in 2009 to 363 in 2012 and 648 in 2015.

It already has heard from more than 225 in the first four months of 2016 — initially budgeting a total of £8,000 ($11,540) for January and February but spending £13,000 ($18,750).

There’s another element to this battle that has her and other activists nervous.

“All these elections of right-wing people across Europe ... It’s not good for reproductive rights,” she said.

Earlier this month, Clarke joined a handful of women outside a London police station protesting the Northern Ireland criminal prosecution.

After an impassioned speech, Clarke and those present walked 14 minutes to the Polish Embassy — because Northern Ireland isn’t the only place where Europe’s abortion laws are coming under fire.

NEXT IN THIS SERIES: 'Coat Hanger Rebellion' Grips Poland