Editor’s Note: This article has been updated to address questions raised by Philadelphia Water after initial publication. The initial article did not make clear that all homes tested in Philadelphia have lead elements and are therefore at high risk for lead in drinking water. The phrases “high risk” and “low risk “have been replaced by “higher” and “highest risk” and "lower risk" respectively to reflect that.

Philadelphia’s water passed its last round of lead testing with flying colors, but documents obtained by NBC News show those results may offer a misleading picture of the lead flowing from Philly taps.

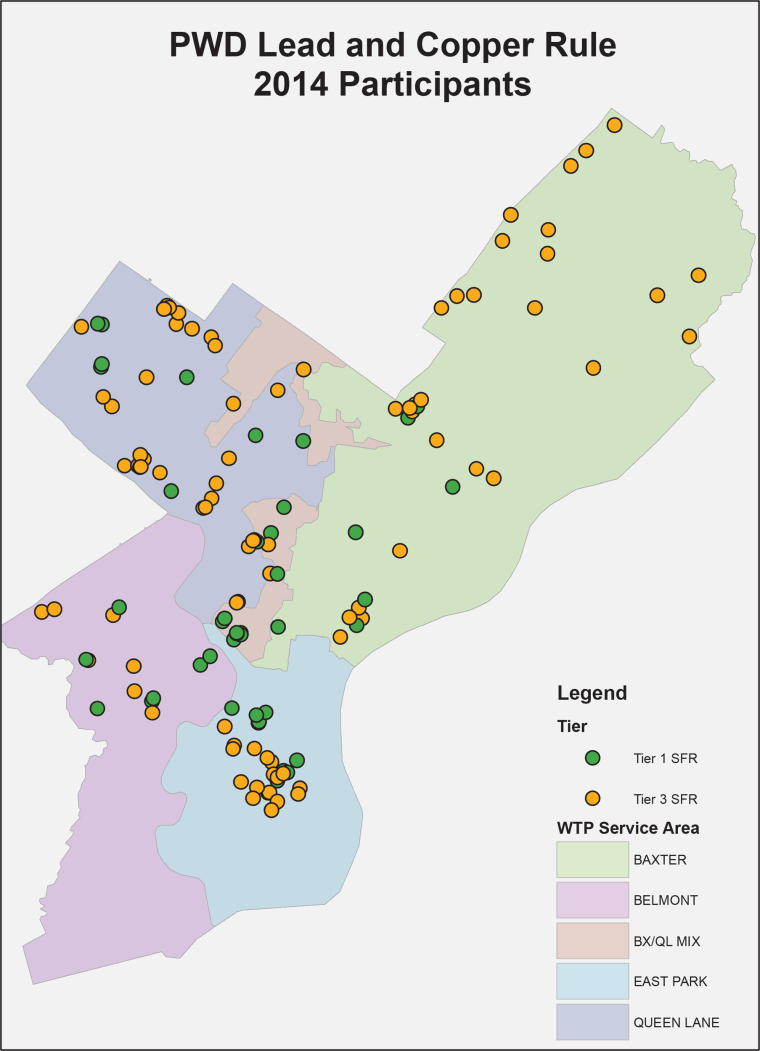

A memo obtained by NBC News shows that in 2014, in a city with up to 50,000 homes with lead service lines, Philadelphia based its clean bill of health on sampling just 42 homes with lead service lines or pipes with highest-risk lead solder out of 134 homes tested — a lower percentage than state and federal regulators advise. Instead, the city tested far more homes without lead pipes or highest-risk solder. After inquiries from NBC News, the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection said it is now reviewing Philadelphia’s data.

Experts say the choice of houses, coupled with other flaws in the city’s testing methods, may be offering Philly’s residents false comfort about the quality of their water – and are a symptom of nationwide testing failures that may have masked lead problems in cities across the country, including Flint. Compared to some other U.S. utilities, Philadelphia Water has a reputation for being well-run and resourced.

“I have the utmost respect for the folks in Philadelphia, and if this is what’s going on in Philadelphia I shudder to think what’s going on in the rest of the country,” said Dr. Marc Edwards, a Virginia Tech researcher who was key to exposing the Flint lead crisis.

State and local officials are struggling to follow a federal regulation known as the Lead and Copper Rule that’s designed to gauge whether a utility is properly treating its water to prevent corrosion of pipes that would leach heavy metals like lead into the water.

The 1991 rule directs utilities to identify a pool of homes at highest risk for leaching lead. Utilities then ask residents if they are willing to participate, and those residents who agree collect samples from their homes for testing.

Under the rule, utilities are intended to prioritize "Tier 1" homes. “Tier 1” refers to single-family homes with lead service lines, lead pipes or copper pipes with lead solder dating from after 1982, considered highest-risk lead solder.

Cities are supposed to draw all their test homes from “Tier 1.” According to state and federal guidelines, 50 percent of those homes are supposed to have lead service lines, and the other 50 are supposed to have highest-risk new lead solder.

If they can’t find enough “Tier 1” homes, they’re instructed to use “Tier 2” homes, which are multi-family homes with lead service lines, lead pipes or highest-risk lead solder.

As the law puts it, “Any community water system with insufficient tier 1 sampling sites shall complete its sampling pool with “Tier 2 sampling sites”, consisting of buildings, including multiple-family residences that: (i) Contain copper pipes with lead solder installed after 1982 or contain lead pipes; and/or (ii) Are served by a lead service line.”

If there aren’t sufficient “Tier 1” and “Tier 2” homes, cities can test a third category of homes that don’t have lead pipes, lead service lines or new lead solder. "Tier 3" residences are single-family homes with copper pipes joined by lead solder from prior to 1983, which, though still a risk, is thought less likely to leach lead than newer lead solder.

According to both the EPA and the DEP, if 90 percent of homes tested register below the “action level” of 15 parts per billion of lead, the system is considered compliant. The rule hinged on making sure the utility focused on the highest-risk homes in order to get a worst-case picture of the system.

But documents obtained by NBC News show that the percentage of highest-risk, “Tier 1” homes tested by Philadelphia Water has dropped over the years, and that in 2014 the city got more than two-thirds of its results from “Tier 3” homes.

A city like Philadelphia, which has thousands of lead lines, should have been able to find sufficient "Tier 1" homes, said Edwards of Virginia Tech.

"Provide me with the addresses and phone numbers of Philly homes with lead pipe, and the funding, and we will sample hundreds of those homes,” he stated. “I am shocked and saddened by their excuses for failing to meet the minimum requirements of the law."

In 2002, 54 of the homes tested in Philadelphia were highest-risk “Tier 1” homes, meaning they had lead pipes or copper pipes with lead solder laid just before the lead solder ban in 1986. The city tested a total of 63 homes. Only nine were the lower risk “Tier 3.”

That year, Philadelphia’s all-important 90th percentile — the result that triggers its overall grade — came in at 13 parts per billion, just two points under the “action level” that requires utilities warn customers of the risk. Five “Tier 1” houses tested high, as did one “Tier 3” home.

By the following round of testing three years later, most of the homes that tested high for lead had dropped out of the testing pool. Since then, the number of highest-risk homes in the test group has dwindled while the overall pool of tested homes has grown. And the city’s results have improved.

In 2014, Philadelphia tested just 34 homes with lead lines, and eight with highest-risk lead solder. Those 42 “Tier 1” homes made up less than a third of the 134 homes tested.*

That year, the city’s 90th percentile had 5 ppb of lead in its water, well under the 15 ppb action level. Eight results tested high that year — three “Tier 1” homes, and five “Tier 3” homes.

The trend of testing lower-risk “Tier 3” homes is combined with sampling instructions for test homes, first revealed in documents obtained by the Guardian, that experts say may also skew the results downward.

Residents are told to remove their tap aerator and run their water for two minutes “6 or more hours BEFORE the water sampling” to clear hot water out of the line. But EPA experts say running the water before testing, known as “pre-flushing,” can produce misleading results and has been used in other cities, like Flint.

“This clears particulate lead out of the plumbing and biases the results low,” wrote EPA scientist Miguel Del Toral in a February 2015 email about Flint’s testing obtained by researchers at Virginia Tech. This practice “provides false reassurance about the true lead levels in the water,” he added.

Asked if Philadelphia’s method of choosing homes and “pre-flushing” could skew results, EPA water expert Mike Schock said, “In my technical opinion, yes it would.”

Philadelphia counters that its testing methods paint an accurate picture of a city where high lead is an anomaly, not the rule.

“It’s not clear that the way we’re taking samples is hiding problems,” said Gary Burlingame, director of Philadelphia Water’s Bureau of Laboratory Services. “Could we be missing homes out there that have higher lead levels than others? Of course."

After the initial publication of the article, Philadelphia Water sent a letter contesting the suggestion that it was not in compliance with state law. The utility told NBC News that it had actually tested more homes than the minimum required by law. As a city that has been found compliant in the past, it is only required by the state and the federal government to test a total of 50 homes.

“The state requires a minimum of 50 homes – 25 with lead service lines and 25 with lead solder. Our testing far exceeded both requirements. … PWD recruited 134 homes that were eligible under the high-risk categories. PWD went above and beyond the sampling pool required.”

However, Edwards says the 50/50 requirement for lead lines and lead solder was intended to apply to Tier 1 homes. Only eight of the lead solder homes in the Philadelphia test group were Tier 1. He said that 50 percent of Philadelphia’s total test group of 134 homes should have had lead lines.

“The rule says it’s a minimum 50 percent homes with lead pipe,” said Edwards. “End of story. If you’re not getting that, you’re not getting the highest-risk homes.”

“This all hinges on finding the worst-case homes. If you truly are sampling the worst case homes, and they come out okay, you can be reasonably assured that the rest of the city is okay.”

Utilities across the U.S. have told regulators about the challenges of meeting the federal rule’s demands. Cities must solicit volunteers for their water studies, and then ask the volunteers to collect the samples themselves. In its memo to regulators, Philadelphia Water said it sent over 8,000 letters to customers, and only 134 had followed through the process.

“People aren’t responding,” said Burlingame, adding that residents don’t continue testing from one year to the next. “Lead in water just hasn’t been something that’s been a national issue.”

The DEP accepted Philadelphia’s results, and the city’s argument that it was not able to get more highest-risk “Tier 1” homes. This despite the state agency’s own guidance that, in accord with the federal rule, at least half of the homes tested in cities like Philly, with old homes and lots of lead pipes, should be high-risk.

The state also has guidance advising that any homes tested beyond the required number must be highest-risk “Tier 1” so as not to “dilute” the testing pool. Philadelphia was only required to test 50 homes in total, but tested 134 — most of them lower-risk “Tier 3.” Burlingame said the utility tested the extra homes because it believed a larger pool would give a more accurate picture of the system.

He added that flushing the line was only to clear any hot water from the tap because the federal rule is designed to test cold water.

The DEP said that while half of homes tested should be highest risk, sometimes a utility is not able to find enough homes with lead lines. However, the agency said it is now reviewing the data submitted by Philadelphia.

The agency also said that Philadelphia had not “diluted” its pool in 2014, despite the extra"Tier 3" homes in the sample, because more “Tier 3” homes had tested high than higher-risk “Tier 1” homes.

“The tier 3 sample actually skewed the overall sample level higher, while still registering below action levels,” the DEP said in a statement. Burlingame also said the city has seen problems in lower-risk “Tier 3” homes in the past.

In addition, both the DEP and the EPA have issued explicit guidance telling utilities not to remove aerators when testing. But the DEP said it can’t make utilities comply.

“Both state and federal guidelines do recommend that aerators not be removed,” said a DEP spokesperson. “However, states cannot enforce recommendations or guidance.”

Flaws in testing have not stopped officials across the country from trying to calm the fears of residents in the wake of Flint. Earlier this month, based on testing results from Philadelphia and more than 150 other state water utilities that came in under the “action level,” the state DEP told Pennsylvanians that “drinking water is not the source” of elevated lead levels found in some of the state’s children.

DEP Secretary John Quigley sent a clear message to the people of the state: “DEP has regulations and programs in place to monitor lead levels in drinking water, and they are working.”

* NBC News submitted a records request to Philadelphia Water for the results of all testing done to comply with federal rules for the last 13 years, as well as any federally compliant tests the city did not include in its final count. Our story is based on the records provided pursuant to that request. After the initial publication of this article, Philadelphia Water said it had tested an additional 155 homes since 2011 and “those results indicate no difference from these compliance samples.” We did not receive and have not reviewed the 155 additional test results referenced by Philadelphia Water.