ROKKASHO, Japan — With its turquoise-striped walls and massive steel cooling towers, the new industrial complex rising from bluffs above the Pacific Ocean looks like it might produce consumer electronics.

But in reality the plant 700 kilometers north of Tokyo is one of the world’s newest, largest and most controversial production facilities for a nuclear explosive material. The factory’s private owners said three months ago that after several decades of construction, it will be ready to open in October, as part of a government-supported effort to create special fuel for the country’s future nuclear power plants.

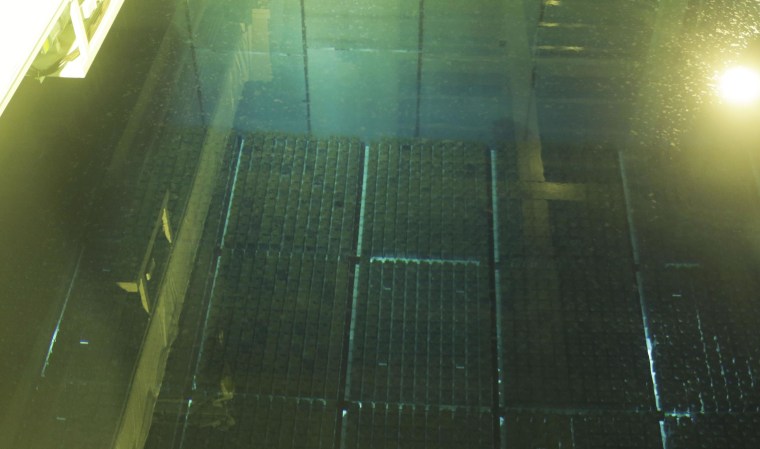

Once it’s running, sometime after October, the plant will produce thousands of gallon-sized steel canisters containing a flour-like mixture of waste uranium and plutonium. In theory, the plutonium is capable of providing the fuel for a huge nuclear arsenal, in a country that protects its nuclear plants with unarmed guards and has resisted U.S. pleas to upgrade security.

Related Story: Japan Has Nuclear 'Bomb in the Basement'

Already, Japan has 9.3 metric tons of plutonium stored at Rokkasho and nine other sites in the island nation, along with around 35 tons of plutonium stored in France and the United Kingdom. Altogether, Japan has the fifth-largest plutonium stockpile of any nation, representing 9 percent of the world’s stocks under civilian control. The figure includes 730 pounds of high-grade plutonium, the kind preferred by weapons designers, that Japan has agreed to send to the United States.

Once the Nuclear Fuel Reprocessing Center at Rokkasho opens, the size of this stockpile could double in five and a half years. That's because Japan is 20 years from completing the first of the reactors designed to burn the plutonium Rokkasho will produce. And an interim plan to burn it in standard reactors depends on a government push to restart the country's nuclear power industry, an action that faces political and regulatory hurdles.

When the plant is operating at full capacity, it’s supposed to produce 8 metric tons of plutonium annually. That’s enough to make an estimated 2,600 nuclear weapons, each with the explosive force of 20,000 tons of TNT.

A six-and-a-half pound lump of plutonium— enough to make a weapon — is the size of a grapefruit. The point, critics say, is that a thermos full of the metal in the wrong hands could produce a devastating terror attack.

The Rokkasho plant is the cornerstone of a plan to build the world’s first energy system based on plutonium-powered breeder reactors, which produce more plutonium than they consume. Japan’s leaders affirmed last month they intend to proceed with that effort, a decision that has stoked anxiety in East Asia and set off alarms among Western experts who worry about the spread of nuclear weapons technology — including some inside the Obama administration.

More coverage on this topic from the Center for Public Integrity

Publicly, the United States has said little about Japan’s plans, which could enlarge its already substantial hoard of plutonium. But since President Barack Obama was first elected, Washington has been lobbying furiously behind the scenes, trying to persuade Japan that terrorists might regard Rokkasho’s new stockpile of plutonium as an irresistible target — and to convince Japanese officials they should better protect this dangerous raw material.

Specifically, U.S. officials have struggled, without success so far, to persuade Japan to create a more capable security force at the plant than the white-gloved, unarmed guards and small police unit stationed here now. They also have been trying to persuade the privacy-minded Japanese to undertake stringent background checks for the 2,400 workers employed here.

It’s been a hard sell for Washington, according to experts and officials in both countries familiar with the diplomatic dialogue. With U.S. prodding, Japan has gradually heightened security at Rokkasho and other nuclear sites, but officials in Washington say they remain worried that the improvements are too slow and incremental.

The dialogue highlights a vast gulf in the two countries’ security cultures. Japan has been far less ready than the United States to imagine and prepare for nuclear-related disasters; its federal agencies have deferred to state and utility officials on safety and security issues; and its political leaders have shown little interest in cooperating with U.S. and other Western experts to improve its standards.

Some Japanese officials have told their American counterparts that the homogenous, pacifist nature of their society makes nuclear conspiracies unlikely — a conclusion that U.S. officials and independent experts categorically reject. Other Japanese officials have insisted that in a nation where gun ownership is rare and privacy rights are zealously guarded, armed guards and background checks are unacceptable at even at the riskiest sites.

“It is a system that relies heavily on the expectation that everyone will do what they are expected to do,” said a senior Obama administration official. As a result, “the stuff we would kind of expect to see” at a dangerous nuclear facility “is not there.”

Long resistance to U.S. pressure

After a U.S. embassy science officer witnessed a security drill in 2006 at the Mihama nuclear power plant along Japan’s northern shoreline, the officer sent a classified cable back to the State Department noting the typical police presence: “a lightly armored police vehicle with up to six police officers — some of them fast asleep.”

This sardonic observation, which appeared in a cable published in 2011 by Wikileaks, came after years of prodding by Washington for tougher security around Japan’s nuclear installations. The U.S. campaign was inspired partly by America’s discovery in 2002 that the 9/11 attackers had initially considered a plan to crash planes into U.S. nuclear power plants.

The U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission responded by ordering U.S. plants to improve physical security, tighten access, improve guard training and compose new emergency response plans. Security forces grew by 60 percent, to about 9,000 officers, according to the Nuclear Energy Institute. Washington also pressed others, including France, Britain, Russia, Japan and China, to take a similar get-tough approach.

But in Japan, at least, there was resistance.

Paul Dickman, a former Energy Department official and chief of staff to the chairman of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission under President George W. Bush, says that when he asked a Tokyo Electric Power Co. official after 9/11 why the company hadn’t toughened security measures faster at the Kashiwazaki-Kariwa plant, the world’s largest nuclear power station, he was surprised by the reply.

“We are in the process of making those changes, but we don’t want to do them all at once because we don’t want people to think that we have been operating them unsafely in the past,” the official said, according to Dickman.

Kevin Maher, the chief science and technology officer at the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo from 2001 to 2005, said that when he and White House homeland security adviser Frances Townsend met there in 2005 with a senior official at Japan’s Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency, “We told him, ‘Your nuclear power plants are very good targets’ ” for terrorists and that security urgently needed to be tightened.

Maher cannot recall the official’s name but distinctly recalls the reply: The official said, “There is no threat from terrorists because guns are illegal in Japan.” Maher said Townsend turned to him and asked: “Is he joking?” The official’s view, he said, was widely shared inside the Japanese government.

“That’s what we were up against,” Maher said.

Townsend, in an interview, confirmed the account and said her impression was that “the Japanese thought of themselves as very much isolated from this particular threat, that it was an American concern that didn’t touch them.”

The Mihama drill, the first of its kind in Japan, included 2,000 participants, including local residents, industry officials, members of the Self-Defense Forces, and some police. But they followed a tightly written script “with no surprises thrown in,” the U.S. science officer said, and the exercise lacked a simulated attack.

The motive for the drill, the diplomat wrote, was fear of a mortar attack against nuclear plants by North Korean saboteurs who could readily reach the Japanese coastline. But there was no “force-on-force” simulation like those routinely included in U.S. exercises.

Two years later, when U.S. Chargé d’Affaires Joseph Donovan expressed his own, broader concerns to two deputy safety directors at Japan’s Science and Technology Ministry, they responded that the contract guard forces at Japan’s nuclear facilities are “prevented by law from carrying weapons,” according to a confidential cable Donovan sent to Washington.

When he specifically challenged the absence of armed guards at a Japanese research center stocked with plutonium and weapons-grade uranium sent from the United States and Britain in the 1960s, the officials “responded that an assessment of local needs and resources had indicated that there was not a sufficient threat to justify armed police” there, according to the cable, also published by Wikileaks.

The deputies said further that background checks for plant workers were unconstitutional and that the government wanted “to avoid raising what is a deeply sensitive privacy issue for Japanese society.” But they also said some checks might be going on “unofficially.”

The situation has hardly improved since then, the senior Obama administration official said in a recent interview, speaking on condition of anonymity due to the sensitivity of such conversations. The devastating accident at Fukushima showed, he said, that police and lightly armed Japanese Coast Guard forces play a secondary role in security and safety emergencies to private, unarmed security guards. The Japanese government, he said, is heavily dependent on what the utilities decide to do.

The official added that although Japan has recently staged counter-terror exercises at nuclear plants, including Rokkasho, and allowed some Americans to watch, “they remain very heavily scripted.” The aim is not to embarrass anyone. “There is great sensitivity to that,” the official said.

John Thomas Schieffer, the U.S. ambassador to Japan from 2005 to 2009, said Japan’s approach to nuclear security can be explained partly by its history. During the Second World War, the Imperial government’s huge domestic intelligence apparatus — including the notorious Military Police Corps — kept a close watch on all Japanese citizens.

“They didn’t want to return to the sort of police state they had during the war,” Schieffer said. Also, “the Japanese had a hard time in the beginning conceptualizing that somebody would want to do something in Japan that would result in a loss of life.”

Another former State Department official who served in Tokyo in the 2000s noted that “their view was that they had everything under control. They lived on an island. They had very few enemies. They were just looking at this from an entirely different perspective than us.”

A pacifist culture?

But Japan has not been immune from terrorism. Japanese Red Army hijackers commandeered several Japanese airliners in the 1970s, and three of its members staged an attack at Tel Aviv’s Lod Airport that killed 26 people in 1972.

Militant members of another group used a flame thrower to set fire to the ruling Liberal Democratic Party’s Tokyo headquarters in 1984. They fired mortars at Tokyo’s Haneda airport a year later and launched home-made missiles against the Imperial Palace and U.S. Embassy during a meeting of the leaders of the Group of Seven industrial nations in 1997.

Most alarming, however, was the long-term obsession of the Aum Shinrikyo doomsday cult with acquiring an atomic weapon. Followers of the cult’s guru, Shoko Asahara, traveled to Russia to buy them and recruit former Soviet weapons scientists. Investigators reported that the group was prepared to pay as much as $15 million for a warhead. In 1993, the group bought a sheep ranch in Australia, where 25 of Asahara’s followers tried to mine uranium to fuel a bomb.

When those schemes failed, Asahara turned to home-brewed biological and chemical weapons, ultimately ordering a sarin nerve gas attack on the Tokyo subway system in 1995 that killed 13 people and injured 6,000 others. He is currently in prison awaiting execution.

Even after the arrest of its leadership, remnants of Aum studied Japan’s nuclear industry. Tokyo police in 2000 said Aum-affiliated hackers had obtained schedules of nuclear fuel deliveries, studied the cooling system at Japan’s plutonium-fueled Monju prototype breeder reactor, and built dossiers on 75 Japanese researchers doing nuclear-related work.

A 2011 report by Richard Danzig, former Navy secretary and a current member of President Obama’s four-member Intelligence Advisory Board, found that “police pursuit of Aum was remarkably lax.” The cult was shielded from close scrutiny by Japanese privacy and religious-freedom protections, as well as a conviction by authorities that it was a collection of harmless cranks.

Terrorist Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who was captured in May 2003, told interrogators that he had tried to recruit hijackers to seize an airliner at Tokyo’s Narita airport and crash it into the U.S. Embassy in the center of the crowded city. Because of restrictions on sharing classified information with Japan, Schieffer said, he wasn’t able to tell Japanese officials that Tokyo had been a target of Al Qaeda for years, until Mohammed’s confession became public in March 2007.

“It upset the Japanese greatly when they found out about it,” he said.

For years, however, Japan resisted taking steps that would have made it possible to share classified information with the United States about nuclear threats, partly out of concern that doing so might weaken public support for nuclear power, according to another U.S. diplomatic cable published by Wikileaks.

Yasuyoshi Komizo, a nonproliferation official in Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, told a delegation from the U.S. Department of Energy in 2008 the government worried that “if, for example, the information sharing concerned potential insider threats, that could be interpreted as suggesting that some segment of the Japanese population was a problem,” the cable quoted him as saying.

A law giving the government sweeping powers to classify information was passed at the insistence of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in December last year. But it hasn’t quelled U.S. concerns.

For a decade the United States has urged Japan “in a friendly way, in a nonthreatening way, to elevate their understanding of the threat,” said the senior Obama administration official. “Do they have the weapons and defensive systems that we have at nuclear facilities? Almost certainly not,” the official said. Instead, Japan has treated the security of their nuclear facilities — all of them civilian — as more of a law-enforcement task than a quasi-military mission.

“History so far hasn’t proven them wrong,” the official said. “But you have to ask, what level of risk are you willing to accept?” The closer Rokkasho is opening, the more urgent the question becomes.

A difference of opinion inside Japan

Kaoru Yoshida, director of media relations for Japan Nuclear Fuel Ltd., the utility that will operate the plant, is well-known to Japanese media as the combative chief spokesman for the Tokyo Electric Power Co. during the early months of the Fukushima crisis.

Yoshida said there was no chance that workers at the Rokkasho plant would try to pilfer any plutonium. “We think we have a 100 percent guarantee that the people working here would not do that,” he said.

He also questioned why terrorists would target the plant, because, he said, Rokkasho’s mixture of plutonium and waste uranium can’t be used to make a bomb. “Because the plutonium is mixed already with uranium, because of the security level that we have here, we don’t have plutonium itself,” he said. “It doesn’t exist here.”

But independent experts say mixing the two nuclear materials does little to reduce the plutonium oxide’s potential to become a bomb fuel.

Dickman, the former NRC official, said the only difference between uranium-plutonium oxide and the pure metallic plutonium preferred by bomb-builders “is a chemist.” Extracting the plutonium from the mixture would not be difficult, he said.

And Nobumasa Sugimoto, director of nuclear security at the government’s new Nuclear Regulation Authority — a group established in part to implement tougher rules in the aftermath of the Fukushima disaster — offered a less sanguine view than Yoshida of the risks at Rokkasho.

Speaking about potential terror attacks on nuclear facilities, Sugimoto said “we believe that these incidents could occur at any time.”

He said that his group, founded a year ago, is particularly concerned about reports that companies with links to Japanese organized crime — tattooed mobsters known as “yakuza” are providing services to the nuclear industry. Hundreds of subcontractors, for example, are working on the government-sponsored cleanup of radioactive fallout in the zone around the devastated Fukushima reactors.

The authority is concerned, Sugimoto said, that if yakuza-connected workers are given sensitive jobs, they could be bribed into conspiring with terrorists to steal materials or mount an attack.

But he added that there is little chance of arming the private security guards at Rokkasho or other nuclear plants. “It’s a very strong and deeply cultural way of thinking, and therefore civilians, although they are security guards, are requested to do their jobs unarmed,” he said.

What if unarmed guards like those at Rokkasho were confronted by armed terrorists? Sugimoto said they are trained to call the police. “The security guards are expected to withdraw for their lives if there is a lethal threat,” he said.

Japan’s prime minister during the Fukushima disaster in 2011, Naoto Kan, said in an interview with the Center that he worries that Japan’s government and industry are still committed to propping up the plutonium program, despite what he now claims are some obvious reasons to cancel it.

Kan, a member of the opposition Democratic Party of Japan, is one of several ex-premiers urging the Abe government to reconsider its commitment to nuclear power — so far without success. Before the disaster, Kan said, he had debriefed some officials with the Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency who had traveled to the U.S. to discuss the terror threat to nuclear plants. NISA, since abolished, was part of the powerful, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, a bastion of support for the nuclear industry.

Kan said the NISA officials returned from their trip unimpressed, telling him they concluded that “America might be under terrorist attacks, but Japan is very unlikely to be so.” Therefore, Kan said, NISA felt it wasn’t necessary to take the threat of attacks on nuclear facilities seriously.

He said this attitude was widely shared in industry and government, and as a result “Japan almost entirely ignored the advice” of the United States after 9/11.

“And you may ask whether Japan is prepared for such threats. Well, the answer is that it isn’t prepared for such attacks,” Kan said.

Toshihiro Okuyama and Yumi Nakayama, staff writers for the Japanese newspaper Asahi Shimbun, contributed reporting for this article.

This story was published by The Center for Public Integrity, a nonprofit, nonpartisan investigative news organization in Washington, D.C. It has been edited for length.