We tend to think of U.S. Latinos in certain cities like Los Angeles or Miami or states like Texas. Yet most of us don't know there is quite a history of Mexicans and Puerto Ricans in Hawaii, or that a small church in Union City, New Jersey helped establish the second largest Cuban community in the U.S.

And while many of us might be under the impression that Latino immigration is a relatively recent thing, at least 80,000 Mexicans already lived in New Mexico, Texas and California by the time Indiana journalist John Soule coined the phrase “Go west, young man" in 1851.

In fact, we go way back. Fifty-five years before the Pilgrims landed in New England, the Spanish had founded Saint Augustine in Florida. Spanish ranchers with wide-brimmed hats were already roping cattle in California by the time Lewis and Clark’s expedition reached Oregon in 1805.

Here are four places where you can reconnect with early Mexican cowboys, Puerto Rican sugarcane workers, Spanish and Cuban cigar makers, and other Latino immigrants.

Hawaii: Our Mexican cowboys and Puerto Rican pineapple harvesters

Latinos make up almost 10 percent of Hawaii’s population, and it turns out the Aloha State has deep Spanish and Latino roots.

The first Spanish immigrant, Francisco de Paula Marín arrived in the late 1700s. He became an adviser to King Kamehameha I, who is credited with the earliest recorded plantings of many fruits and vegetables on the islands, including the first pineapple in 1813.

By the 1850s, Hawaii was already exporting thousands of pineapples to California. And as agricultural industries grew on the islands, recruiters looked towards expert Latino farmers to harvest both pineapples and sugarcane.

Between 1900 and 1901, over 5,000 Puerto Rican men, women and children were recruited by the Hawaiian Sugar Planters’ Association after a hurricane in Puerto Rico devastated the sugar plantations there. By the 1950 census, almost 10,000 Puerto Ricans lived on the islands.

Today, you won’t find any Little San Juans in Hawaii, though some traditions like arroz con gandules - called gandule rice in Hawaii - show the boricua presence. Some point out that Puerto Ricans integrated into the island just like the first wave of maverick Latino immigrants, the paniolos. These were the Spanish-Mexican cowboys who were contracted by ranchers in the 1830s to wrangle wild cattle.

Etymologists believe that “paniolo” comes from the Hawaiian pronunciation for “Español,” meaning “Spanish.” Some researchers also think that the word is derived from “pañuelos,” the colorful handkerchiefs that vaqueros tied around their necks. In either case, paniolos remind us that immigrants are like roaming cowboys who ride to new places in search of work and opportunities.

Tampa, Florida: Our great-grandparents helped build the cigar capital of the world

Like many immigrants today, early Latinos followed different job routes to their new homes. Fisherman, farmers and cannery workers made their way to food industries in California. Granite workers migrated to New England. And miners were recruited for West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and other states.

Make sure to follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

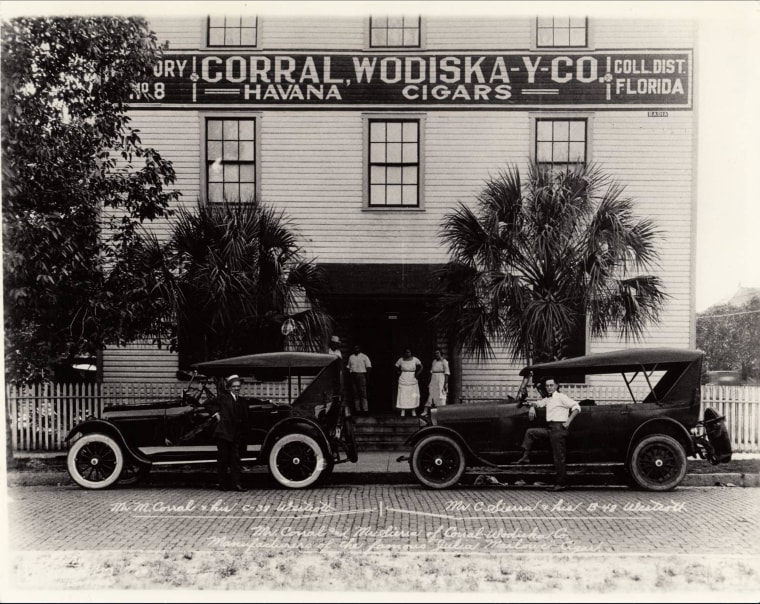

Spanish and Cuban cigar makers similarly followed a route from Cuba to Key West and Tampa Bay. But unlike Latinos in Hawaii and other places, these immigrants did not have to integrate themselves into new communities. According to the documentary "A Legacy of Smoke," a film about Spanish immigrants in Tampa Bay, Spaniards and Cubans were “largely responsible" for the “origin and development of Tampa as a modern city."

A Spanish immigrant from Cuba, Vicente Martínez Ybor, was the first to move his cigar factories from Key West to Tampa in 1865. The humid climate, the Gulf Coast port, and the new rail line that connected New York to Tampa soon attracted more Spanish and Cuban cigar makers, transforming the modest bay into the “mecca” of the cigar industry. By 1929, 151 cigar factories earned just over half of Tampa’s revenue, producing 500 million cigars.

Even though Tampa Bay made many Latinos rich, the cigar factories were also hubs of politics, culture and identity. In 1893, Cuban poet and statesman José Martí rallied support for Cuban independence on the steps of Ybor´s factory. He hoped to channel the solidarity and energy of Cuban tabaqueros to build a new country.

Union City, NJ: A Cuban community with a venerated patron saint

Over 1,100 miles north from Tampa Bay, another group of Cubans gathered in New Jersey, very near the New York City border, to build a community. Before the 1959 Revolution, Union City was a faraway outpost for a few Cuban families who were too small in number to be visible.

Like other immigrants, the Cubans from the 1940s and 1950s hoped to find an easy way to “desenvolverse”, or “get ahead.” They took jobs in embroidery, textile and manufacturing; and some started businesses and social clubs on Bergenline Avenue.

In spite of these early successes, the forefamilies of the second largest “Little Havana” in the U.S. needed a strong national symbol to unite them as a community. And surprisingly, many prerevolutionary immigrants in Union City, who were not practicing Catholics in Cuba, suddenly found that symbol in the patron saint of a local parish.

Yolanda Prieto describes in her book, "The Cubans of Union City" how the Virgin of El Cobre, the patron saint of Cuba, also became a symbol of the first Cuban Catholics in Union City. Parishioners raised money to buy the statue in 1957, had it blessed in Cuba, and then carried it in a procession of 1,000 people through Union City.

Prieto describes how Union City's St. Agustine became a “national parish” for Cubans and other Latinos, setting up networks for exiles who arrived after the 1960s and hosting zarzuelas, Spanish operettas, fashion shows and other social events.

“There is no break here,” said Father Pedro Navarro in the book, a former pastor at St. Agustine. “We try to help solve religious and human problems.” And for Cubans, like other Latinos who feel homesick, establishing roots at a local parish made the emotional distance from Cuba shorter.

Garden City, Kansas: From the beet fields to the meat-packing plants

Traveling through the plains of western Kansas can be a lonely experience. But for Mexican immigrants, the open flat fields offer many opportunities to reinvent themselves.

Latinos in the Midwest have always filled basic labor needs in agriculture, construction, transportation, and other industries. And like many immigrant hubs, Garden City, Kansas, attracted Mexican workers because it was at a crossroads between different job routes.

In the early 1900s, Mexicans worked at sugar plants and beet fields. But in 1980, many of them started moving to meatpacking plants. Robert Wuthnow’s book, “Remaking the Heartland" explains how this new industry made Garden City much more diverse. In just two decades, the Latino population rose from 14 to 43 percent in the county.

Wuthnow points out that while Garden City has always been friendly to Latinos, ethnic diversity also posed many challenges. In 1949, when more than 3,000 people attended the annual Mexican Fiesta, Mexican Americans were “still excluded from restaurants and required to sit in the balcony [of movie theaters],” he wrote in the book.

Recent Latino immigrants in some Midwestern meatpacking towns are struggling to assimilate today. Yet a look back at our history shows this is part of the cycle of immigration and assimilation we have experienced for centuries across varied parts of the U.S.