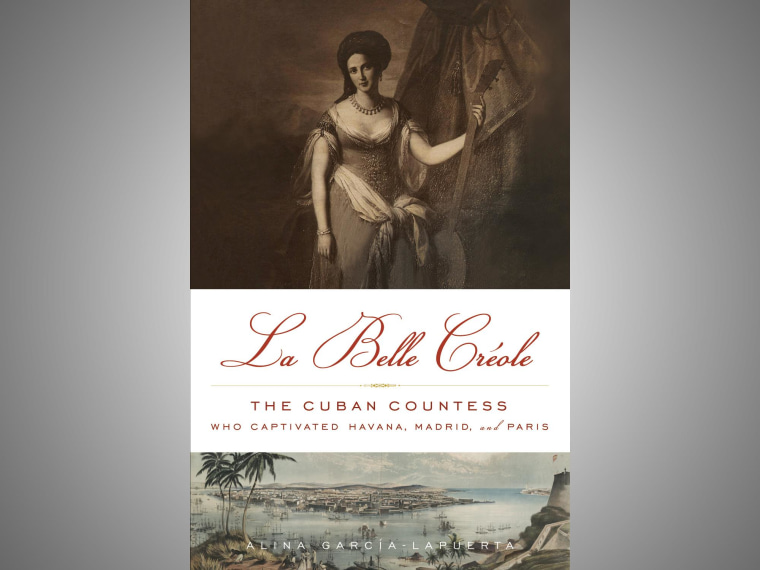

Most of us recognize certain names throughout Latin American and U.S. Latino history – Simon Bolívar, César Chávez and Dolores Huerta, Roberto Clemente or Gabriel García Márquez, to name just a few. Then there is María de las Mercedes Santa Cruz y Montalvo. Never heard of her? Exactly. Author Alina García Lapuerta is on a quest to change that with her new book, La Belle Créole: The Cuban Countess Who Captivated Havana, Madrid and Paris, the first English-language biography of Cuba's first female published author, a socialite and singer who became a big star in 19th-century Paris. Her notable life is also an immigrant success story that resonates with so many of us today, said the book's author.

“I found out about her looking through one of those beautiful coffee table books at a bookstore in Coral Gables, Florida,” said García Lapuerta, a former investment banker who graduated from Georgetown University's School of Foreign Service and Tufts University's Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy. “She was quoted in there and I became curious. I’ve always been fascinated by history and I was amazed that I had never heard of her, so I started doing research."

Seven years later, the author penned a biography that reads like a novella divided into three parts – the protagonist’s life trajectory in Havana, Madrid, and Paris.

“I felt she deserved a biography and deserved to be remembered,” García LaPuerta told NBCNews.com. “She has a fascinating history.”

María de las Mercedes Santa Cruz y Montalvo was born in Cuba into an upper-class family. Her parents left her in the care of a great-grandmother while they went to Spain to serve in the royal court, and brought her to Spain as a 13-year-old.

As García Lapuerta describes in meticulous detail and in a style that easily takes the reader back in time, Mercedes witnessed turbulent events such as Spain's involvement in the Peninsular War with Napoleon Bonaparte’s France. She witnessed the King’s abdication, a long civil war that nearly wiped out her family financially, and life in Spain under Napoleon’s older brother Joseph.

“Many Hispanics can relate to that: you arrive at a foreign country and you do well. It’s a wonderful story of how she overcame obstacles and was very successful at what she did," said the author of the remarkable 19th century Cuban author and socialite.

The young Cuban immigrant eventually married a French general and became Countess Merlin. In 19th century France she became a star of Parisian society, known for her soprano voice and for hosting the city’s most well-known musical salon. She rubbed shoulders with the famous painter Francisco de Goya, composers like Liszt and Rossini, and nobles like the Baron de Rothschild. She also became a well-known writer, publishing her memoirs of her early years in Cuba and then France.

After the death of her husband and after an absence of nearly 40 years, Mercedes returned to Havana, writing about her voyage back to her homeland in the Spanish-language Viaje a la Habana (Voyage to Havana). In her time, she was quite famous, even in the United States, where crowds came out to greet her on her visits. She traveled to Cuba only once more before dying in Paris in 1852 at the age of 63.

In describing her fame, García LaPuerta writes that Santa Cruz y Montalvo was what the French called a femme du monde (a woman of the world). “In becoming a femme du monde, Mercedes united the more obvious gifts of beauty, good birth, and culture with the talents of the artists, the attractions of a witty hostess, and the elegance and stylishness of a trendsetter, along with the nurturing soul of a patroness of the arts."

While Mercedes’ story is centuries old, it still has great relevance today within the immigrant community, said García LaPuerta, explaining this applies to her too. Born in Cuba, the author's family left the island like many other exiles and she was raised in West Palm Beach, Florida. She currently lives abroad with her Spanish economist husband and children.

“Like her there are many others. We may not remember them, and you don’t often hear about them or their stories, but they exist and we should know more about them,” said the author.

“We can all identify with her story. She was a foreigner in France and she works in another language and succeeds," said García Lapuerta. "Many Hispanics can relate to that: you arrive at a foreign country and you do well. It’s a wonderful story of how she overcame obstacles and was very successful at what she did.”

It is also an ode to Latinas throughout the years, said García Lapuerta, the story of a a strong woman who led a fascinating life and broke barriers, reinventing herself along the way. “She was a pioneer. She participated in the public arena and stops being in her family’s shadow. She comes into her own.”

The author is hopeful that one day her story on such a transcendental but little-known character in Latin American history will be translated into Spanish to reach a wider audience.

“Like her there are many others. We may not remember them, and you don’t often hear about them or their stories, but they exist and we should know more about them.”