As we recognize Hispanic Heritage Month, it is worth appreciating the episodes in our history where self-motivation and organization overcame the odds to exact change on a system not traditionally receptive to community interests. The little known formation of a group of women in East Los Angeles, the Mothers of East L.A., known as MELA, was one such significant episode.

Latinos in Los Angeles had experienced a long chain of injustices in the immigrant gateway community; it was illegal to speak Spanish in school until 1969. In the 1970s, Latinos were still feeling marginalized from the running of their city and their say in local and state affairs.

The first Mexican American to work as a reporter for the LA Times, Ruben Salazar, had become a thorn in the side of the police department in Los Angeles for his insistence on investigating reports of abuses against the Latino community. In 1970, he was struck dead after a sheriff's officer fired a tear gas canister into a bar the day of a Chicano/a rally and march. This marked a dark moment for activism among Latinos. The Vietnam War, the oil crisis, and the recession had descended particularly hard on the poor neighborhood of Boyle Heights, the heart of East L.A.

Another pall on the community was its relationship with former Chief of Police Daryl Gates, whose tactics during the Reagan era's War on Drugs were questioned by minority communities. The first chief of police to deploy an armada of helicopters and military-style Special Weapons and Tactics (SWAT) units, many Latinos in East Los Angeles felt they were constantly under surveillance or under siege.

In was in this historical context that many in the community felt a sense of frustration when the California Legislature proposed building a state prison in East Los Angeles in 1984. With local and federal prisons already nearby, a state prison would mark East L.A. as a place where one either went to or awaited incarceration. Freeways had already carved through East Los Angeles, with the famous interchanges between the 5, 10, 710, and 60 freeways piercing the heart of the neighborhood.

Unpopular projects, such as waste-processing plants and prisons, are almost impossible to build in more affluent neighborhoods. The organization and influence in wealthier zip codes exact a high political price on any legislator that attempts to build these unwanted projects. The result is that these proposals often seek out poorer neighborhoods that have less influence to prevent them.

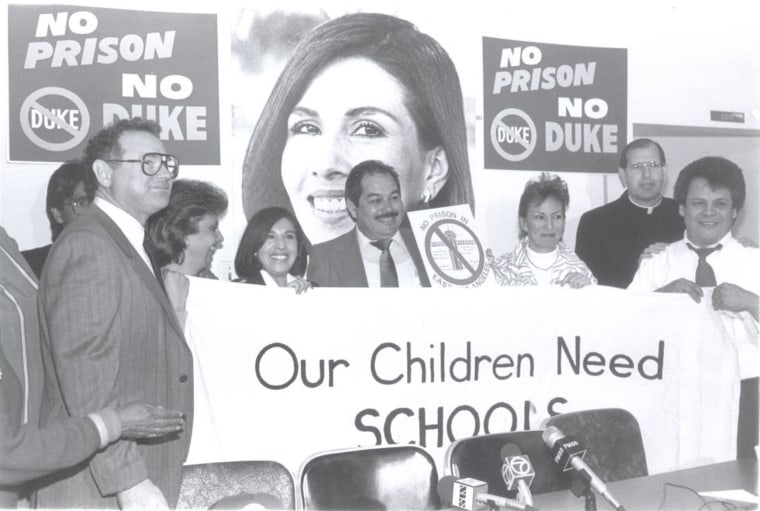

In 1986 a group of Latina mothers started meeting in a Catholic church and proceeded to organize in opposition to the building of the prison. On a weekly basis, hundreds of mothers along with their children and husbands would march against the prison proposal, generating attention and traveling to the state capital, Sacramento, to state their case. They wore white scarves on their heads, and they generated headlines and attention. The fight started in the church basement was ultimately successful; it took over a decade, but the prison was not built in Boyle Heights.

In 1986 a group of Latina mothers started meeting in a Catholic church and proceeded to organize in opposition to the building of a state prison in the predominantly Latino section of Boyle Heights in Los Angeles.

The actions by these unlikely women activists was both profound and inspiring to many. As minority women asserting power in an arena dominated largely by men, they faced the daunting task of managing their identities as political actors that is often in contradiction with their expected roles as Hispanic mothers. However, as women, these activists asserted their power as caretakers of the community and protectors of their families.

Political scientists often write about the importance of civic resources in political participation; reservoirs of experiences, skills, and social networks that can be mobilized towards a common cause. Hardened and battle tested over the previous decades of activism, the Madres del Este de Los Angeles had little power between themselves, but were able to pull on the influence of 47 civic organizations whom they formed as a coalition against the prison.

Martha Molina-Aviles, an activist in MELA, said that the proposal to build the prison had provoked a tenacity among them that was profoundly symbolic. When marching, they could always be identified by their common white scarves tied around their heads. They were warriors, but they were also peace activists, she explained.

Molina-Aviles is now the director of field operations for Los Angeles County Supervisor Gloria Molina, who had helped the Mothers as a young state assemblywoman. Ms. Molina was the first Latina to be elected to the California State Legislature in 1982, and is now running for City Council in Los Angeles.

Mary Pardo, a Professor of Chicano/a Studies at Cal State Northridge chronicled “the Mothers” in her book, Mexican American Women Activists. Pardo explained how the Mothers' active participation in school PTAs and church groups provided them with the foundation to reach out to local legislators, activists and businessmen.

“The strength of the Mothers of East LA was that people trusted them, and when they came to them to share information it wasn’t like a complete stranger trying to ask them to join and be political," said Pardo.

What political scientists have coined as social capital, or the bonds of trust between members of society, was a valuable resource for these activists in leveraging their moral authority against the political and bureaucratic gears of government.

“It was very mush grassroots, so we aren’t talking about an organization that had a building or an office. It was really run out of a woman’s house. She had a large two story house in Boyle Heights," said Pardo.

The group's members also pulled on experiences abroad and historical moments that went beyond our borders. The Mothers of East LA drew from the Argentinian grassroots movement, Las Madres de la Plaza de Mayo; a similar organization of mothers formed in response to Argentina’s “Dirty War” in which thousands of sons and daughters - mainly young men and women - were disappeared, tortured, and killed by the government.

Their contribution and those of grassroots groups like theirs has been overshadowed by assumptions that for change to occur the main requirements are voting and numbers.

Prominent Columbia University Latino scholar Rodolfo de la Garza once said that “demographics is the engine of Latino politics.” As the largest minority population in the United States, popular media has often made the assumption that representation would necessarily follow close behind in our democratic system. But the research on political mobilization has always been reason for political scientists to pause when predicting the awakening of the so-called “sleeping giant”.

As has been said, political participation is about people going to politics, but it's also about politics going to people. As the group of Hispanic mothers-turned-activists shows, it takes more than individuals; it's an actual pueblo that exacts change.

The Mothers still meet on Mondays at the tiny church of the Saint Isabel Parish. Their contribution and those of grassroots groups has been overshadowed by assumptions that for change to occur the main requirements are voting and numbers.

From her experience with the group, Molina-Aviles' takeaway is that “we must take our future into our own hands, to take ownership of our homes against errors that have no boundaries."

Today, the California Legislature knows not only that we will defend ourselves, but that we have the ability to do so," said Molina-Aviles.

Today, Boyle Heights stands as the epicenter of many Latino grassroots movements. From the Chicano movement to the Brown Berets to the United Farm Workers Union, political activism runs deep in this community. As we look at the future, the Mothers of East LA marks another moment for which Latinos can look back with pride at how ordinary neighborhood residents got involved and effected positive change for our community.

Emily Gwash and Austin Schroeder contributed to this report.