Despite growing controversy over the use of anonymous pharmacies for lethal injections, the U.S. Supreme Court has thus far declined to block any executions based on 11th-hour appeals challenging the drug connections.

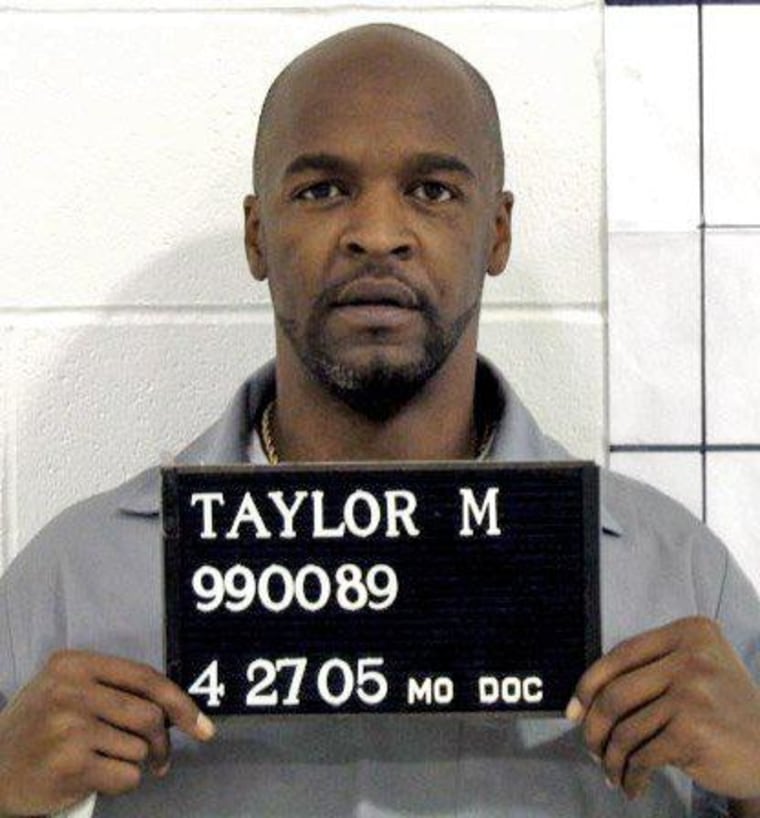

That includes the case of Michael Taylor, a convicted rapist and murderer who was put to death at 12:10 a.m. Wednesday in Missouri after a furious legal battle that stretched into the night.

It's worth nothing, however, that three high court justices wanted to block Taylor's execution and cited the words of an appeals judge who said so little was known about the source of the deadly dose of pentobarbital that it "could be nothing more than a high school chemistry class."

The strongly worded dissent from Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Kermit Bye — echoed by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan — is giving some defense lawyers hope the veil of secrecy will be lifted by the judiciary.

"It seems that the issues raised in Judge Bye's dissent are starting to at least resonate with some members of the Supreme Court," said Allen Bohnert, a federal capital defender from Ohio.

Bohnert represented Dennis McGuire, who was executed in Ohio in January for raping and stabbing to death a pregnant woman. Witnesses said it took 25 minutes for McGuire to die and he gasped for breath after an untried cocktail of drugs hit his bloodstream.

With the supply of drugs traditionally used to carry out executions dwindling, states are scrambling for other sources. At the same time, they are insisting on secrecy, which defense lawyers say makes it impossible to challenge an execution's legality.

"The defendant who's about to be executed might want to claim that what the state is going to do to him is cruel and usual punishment. But he’s not allowed to know the source of drugs or the education of the pharmacist who made them," says Richard Dieter, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, which opposes the death penalty.

"You can't find out whether the maker has been cited for contaminated drugs, because you don't know his name."

Three cases pending before the Supreme Court challenge the use of untested drug protocols and state restrictions on the chemicals' source. And battles to require transparency are being waged in state courts, too.

- Christopher Supulvado, a convicted murder on death row in Louisiana, is challenging that state's lack of disclosure. "Our claim is not that the protocol is bad. Instead, we say we need to know in time what the protocol is, and the state keeps changing it at the last second and not telling us," said his lawyer, Tom Goldstein.

- Georgia's Supreme Court is considering a challenge to a state law, passed last year, that declares information about the source of its drugs to be "a confidential state secret."

- Two Oklahoma inmates, Clayton Lockett and Charles Warner, sued the state Wednesday for refusing to reveal the origin of the drugs for their March executions.

Warner's lawyer, Madeline Cohen, said the dissent in Taylor's execution "is the first sign that some of the justices are concerned with what’s going on."

Added Bohnert, "I would like to think that this untenable bind will be straightened out by the Court at some point, because it effectively obliterates any possibility of showing an Eighth Amendment violation based on problems with execution drugs."

Earlier Challenge

In 2008, the Supreme Court upheld what was then a widely used combination of three drugs, administered in sequence, to carry out a lethal injection.

Opponents claimed if a state failed to properly inject the first of them, an inmate was left awake but paralyzed, in intense pain but unable to cry out. The court said some risk of pain is inherent in any method of execution but that critics did not show another method would be clearly more humane.

Two years after that ruling, the makers of two of the drugs used in the combination decided they no longer wanted to be part of the death penalty process and prison supplies began drying up. In response, states began turning to compounding pharmacies, which are seen as less regulated.

Specialty pharmacies that were unmasked became targets of protests and litigation. A Texas compounder asked for its drugs to be returned; one in Oklahoma agreed not to take part in Taylor's execution, forcing Missouri to turn elsewhere.

States are anxious to shield the dwindling number of suppliers.

In a court filing, Georgia said divulging the identity of execution participants "is likely to subject the drug manufacturers, suppliers, testing labs, and healthcare professionals to harassment, potential loss of business and other adverse consequences."

Nine other states either have similar laws or insist their public records laws allow them to keep the pharmacy names secret, said Jen Moreno of the death penalty clinic at the UC Berkeley School of Law.

Executions have come to a halt in six of the nation's 32 death penalty states, as well as in the federal system, in response to lawsuits over the lethal injection process or concern about untested protocols, she said.

Some that have gone forward have given defense lawyers ammunition to argue the new protocols amount to unconstitutional cruel and unusual punishment.

In the dissent cited by the Supreme Court's Ginsburg, Missouri judge Bye pointed to the January execution of Michael Lee Wilson, condemned to die for beating a co-worker to death in 1995.

He took particular note of Wilson's final six words, uttered 12 seconds after compounded drugs were injected into his veins: "I feel my whole body burning."

NBC News' Tracy Connor contributed to this story.