Flamingos have been Omar Rocha’s passion ever since he saw them for the first time in Laguna Colorada, Bolivia 25 years ago.

“I felt extremely emotional to see them up close, thousands of flamingos together feeding in the wetlands, forming part of the desolate landscape of the high-Andean region,” Rocha said. “I marveled at the sight of them, attracted by their colors, behavior, and elegance. In that moment, I knew I wanted to study and focus my studies and research on these beautiful and charismatic birds.”

Bolivia is unique in that it is one of only four countries that is home to the Chilean flamingo and two other species — the James flamingo and the Andean flamingo, which are the rarest species of flamingo in the world.

Today, the Bolivian is a leader in the conservation of these rare species and is doing all that he can to ensure their survival.

Last month, Rocha and his wife, Sol Aguilar, traveled to the United States to learn valuable skills from bird experts at Sylvan Heights Bird Park in North Carolina.

Established by Mike and Ali Lubbock, who have a long history of involvement with international conservation programs, the park boasts the largest bird collection in the United States. And it is home to three flamingo species: Lesser flamingos, American flamingos, and Chilean flamingos.

General Curator Brad Hazelton worked with the Bolivian couple to show them how to transport eggs in a small, portable incubator, as well as how to monitor the eggs’ incubation. He also trained them on how to hand-raise flamingo chicks, a technique he perfected 12 years ago with an African species of captive flamingos.

The husband and wife team carefully practiced tube-feeding the baby chicks and meticulously translated the protocol and forms they’ll need for keeping records. All of this in the hopes that they can use these new skills to help protect the rare flamingos in their native country.

Since starting his company, Centro de Estudios en Biología Teórica y Aplicada (BIOTA), 14 years ago, Rocha has conducted many research projects on the various habitats and wildlife within Bolivia.

But he says that his passion for the rare flamingos found in the high-Andes started in 1991 when he was working on an evaluation of birds and saw flamingos for the first time in their natural habitat.

“Since then, the project has taken on a life of its own, giving us great satisfaction, traveling and learning about spectacular sites such as the high-Andean wetlands that the flamingos inhabit,” Rocha said.

RELATED: Rare Black Flamingo Ruffles Feathers in Cyprus

BIOTA has been hired by energy and mining companies to conduct research on everything from tracking the migration patterns of high-Andean flamingos to testing the amount of heavy metals in the birds’ blood. They’ve used satellite tracking devices to record the local and international migration routes of Andean and James flamingos, and have used what they’ve learned from their data to make recommendations for proposed power line routes.

“The work we’ve undertaken has allowed us to understand the situation of these three flamingo species in Bolivia so that we can develop projects that benefit their conservation,” Rocha said.

As often as once a month, Rocha makes the 17-hour journey up to Laguna Colorada and surrounding lagoons to carry out his research or conduct a census. Located in the southwestern corner of Bolivia, this shrinking lake is one of a series of vitally important water sources in the stark and arid landscape. Over 14,000 feet above sea level, it turns out that Laguna Colorada is the single most important nesting site for the high-Andean flamingos.

Rocha has figured out that 90 percent of the population of James flamingos nest on this lake, as do Andean and Chilean flamingos. Not one to squander an opportunity, Rocha has been spearheading a flamingo banding program there for the past 18 years. His strongest supporter and partner in the preservation of these species is his wife, Sol Aguilar. “For 15 years we’ve been a good team, sometimes taking turns traveling and taking care of our children at home,” Rocha says.

RELATED: World's oldest known flamingo dies aged 83

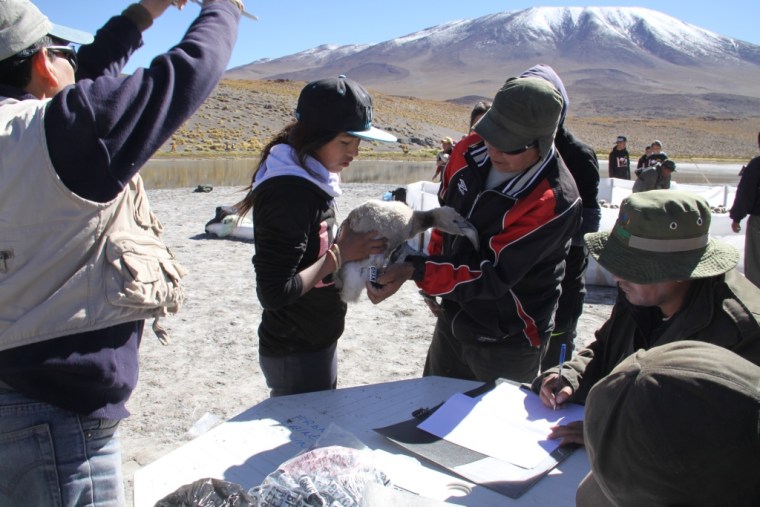

Every summer, at the end of March, the two of them lead a group of volunteers in the round-up and banding of up to 1,000 baby flamingos. In the wild, baby flamingos are raised in something like a nursery group, called a crèche. During the day, these babies remain together in these large groups that are watched over by a few flamingos while the rest of the parents feed, sometimes in other lakes.

The couple takes advantage of this rearing habit to gather the young birds together and place ID bracelets on their legs. Working with the park rangers, Rocha’s day begins before dawn when he and his crew head down to the lagoon to build a temporary corral on the shore. Then the more experienced park rangers walk around the lagoon to select a crèche and begin herding the chicks toward the corral. By 10 a.m., the real work begins as Rocha and his group of up to 50 volunteers begin methodically transporting the baby flamingos, one by one, to banding tables before being released back on the water.

The banding program is supported by organizations as far away as the Bronx Zoo, which, during the last few years, has sent not only volunteers to help but has donated the bands placed on the birds, as well. And volunteers come from all over Bolivia. They include park rangers from other national parks and local high-school students, whom Rocha and his wife enlisted to participate.

RELATED: Pink flamingos make slow return to Florida

Their motive was two-fold: to find extra hands to help with the banding, and to try and engage these local students in the hopes that they will be inspired to become active in flamingo conservation. The latter is of extreme importance because one of the challenges Rocha faces in his conservation efforts is the local indigenous community. For them, the rare flamingo eggs are a delicacy. And they are able to collect them as part of an agreement that they have with the Bolivian government, citing it as a cultural right.

So, once a year, members of the community make their way into the middle of the lagoon to the flamingo nest areas and collect the flamingo eggs. Unfortunately, only fresh eggs are considered edible, and so those with embryos are typically thrown out.

Disturbed by this loss of life, Rocha has been exploring ways to minimize the impact to the wild population and reduce the waste. He’s come up with a plan to rescue those discarded embryos in a way that will benefit the long-term conservation of the species.

Working together with the zoo in La Paz, Rocha plans to transport the developing eggs back to the zoo, where he hopes to hatch and raise them to establish a captive population as a hedge against extinction, should anything happen to the wild population. The captive group will also serve to educate the public. Currently, no zoo in Bolivia has flamingos on display and many people do not know about these unique birds.

Rocha is hopeful that the time they spent at Sylvan Heights and the skills they learned will prove beneficial as they move forward in their efforts to preserve this beloved species.

“This was a marvelous experience for us since we’ve always studied flamingos in the wild and we didn’t have any experience in the care and management of captive flamingos,” Rocha said. “It’s motivated us to develop initiatives such as incorporating flamingos into our zoos to serve as educational ambassadors and apply what we’ve learned.”