Ocean scientists often say that humans know more about the surface of Mars than the seafloor of Earth.

Under the icy water surrounding Earth's poles, there's a hidden world of dramatic landscapes — ancient canyons, craters, hills, and fields. A group of scientists has compiled a new atlas of some of those formations and released images from the collection on Tuesday (April 25) at the annual meeting of the European Geosciences Union in Vienna.

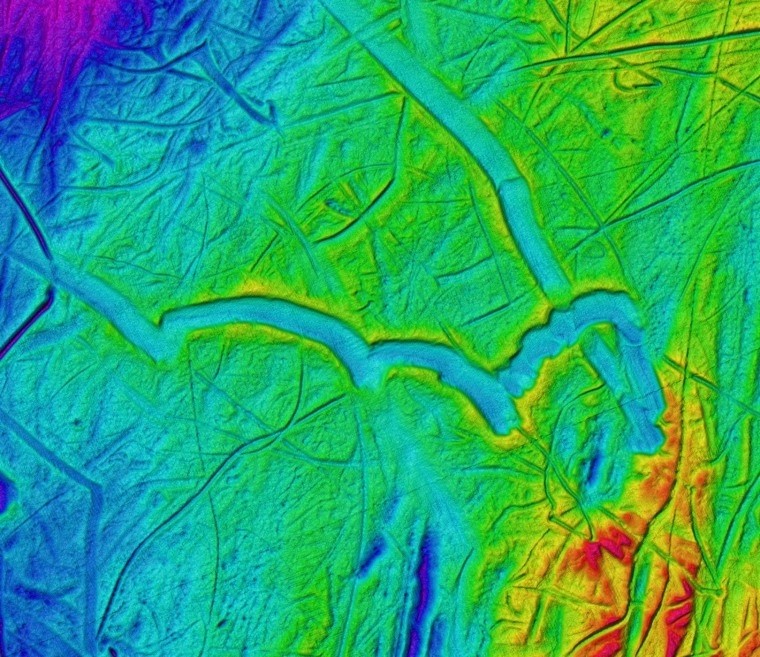

The 200-plus images in the "Atlas of Submarine Glacial Landforms" reveal the "fingerprints" that past glaciers and ice sheets left on the seafloor, Kelly Hogan, a marine geophysicist with the British Antarctic Survey, told reporters during a news conference.

Related: See Images of Hidden Landscapes from the Underwater Atlas

In all, about 250 scientists from 20 countries contributed to the new atlas. Most of the high-resolution,3D seafloor imagery was obtained by acoustic methods like multibeam sonar, where sensors on research ships send sound signals to the seafloor and record the responses back up to the ship.

"I like to think of this as remote sensing of the seafloor," Hogan said. "In the same way that satellites are moving around the globe and sending down a pulse and receiving the signal back and putting together a whole picture of the planet, this is what we're doing on the ships."

But satellites in space don't have to navigate pack ice. Researchers who study the seafloor can take images of only those areas they can sail near, so there are still a lot of blank spots in the underwater topography around the poles. The total area of the images covered in the atlas would fill a region about the size of Great Britain. Nonetheless, chief editor of the atlas, Julian Dowdeswell, director of the Scott Polar Research Institute, told Live Science that over 95 percent of the types of landforms you would find on the seabed are likely represented in the new collection.

The formations include a range of geological phenomena, from the once-exposed ridges left behind by fast-moving glaciers to the squiggly plough marks that have been etched into the seafloor by the keels of massive icebergs. Studying these formations could help scientists reconstruct past climates and environments.

Related: See Time-Lapse Photos of Retreating Glaciers

"Often these features are very well-preserved because there's no humans, there's no roads, there's no weathering," Hogan said. For example, she described a former permafrost field in the shallow Laptev Sea in Eastern Siberia that was submerged when sea levels rose at least 6,000 years ago. "What these permafrost patterns tell us is that although this area was permanently frozen during the last glacial [period], it wasn't covered by grounded ice. This tells us exactly the environmental history of that area."

Retreating glaciers and ice sheets are among the biggest concerns of scientists trying to understand the effects of climate change today, and Hogan hopes the glacial history preserved underwater could help scientists predict how ice will behave under different conditions in the future.

"If we can find information from the seafloor about what stabilizes ice when it retreats or about how quickly it flows over different materials on the seafloor, then it means we can contribute that knowledge to the ice sheet modelers today," she said.

Original article on LiveScience.

Editor's Recommendations