Volunteers from Cape Town to Brooklyn are surveying the Philippines' storm-ravaged landscapes, helping to identify areas where help is needed most, just by clicking on images and tweets. Though it's as easy as flipping through Facebook photos, deciding what to “like,” participating in this MicroMappers project does real good, providing eye-in-the-sky guidance to United Nations-backed relief workers on the ground.

Since Friday, when Typhoon Haiyan (also called Yolanda) made landfall, participants in the project, hosted on the CrowdCrafting website, have sifted Twitter posts and uploaded photos from Filipino users, filtering for rare-but-valuable updates, images and information that point to areas where help is needed most.

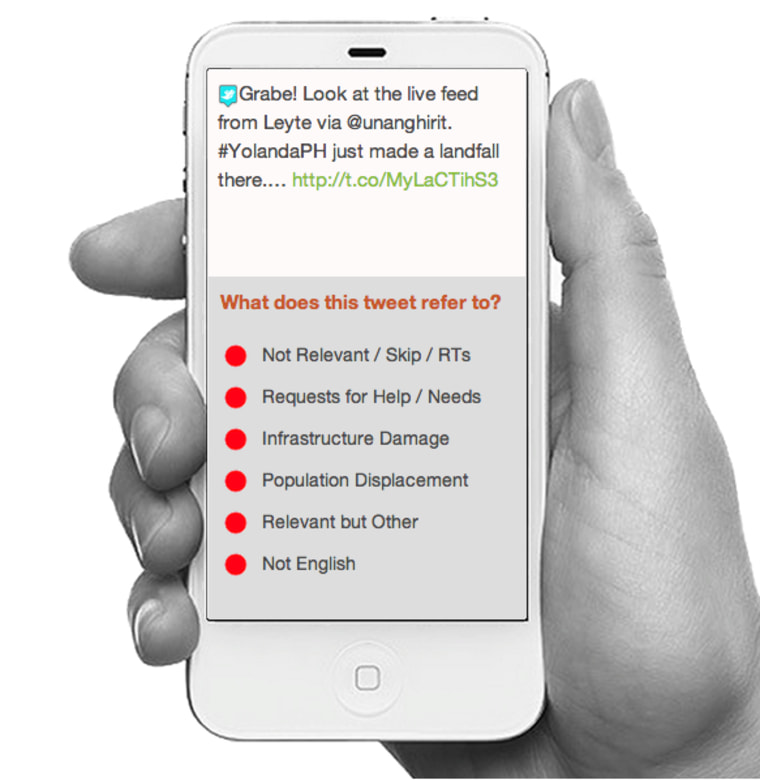

Tweets can be tagged as “request for help,” “infrastructure damage,” “population displacement,” “not relevant” and “not English” via the TweetClicker. Photos are classified according to the amount of damage they show: “severe,” “mild” or “none,” via the ImageClicker. Each item is shown to three participants, and is only submitted for review if all three volunteers have rated it as relevant. Though algorithms clear out a lot of the retweets and other empty messages before they reach the volunteers, there's a lot of hashtags to click through, not to mention posts for fundraisers and from people simply expressing their concern.

Needless to say, amid the cacophony of social media that so often spikes during a crisis, “not relevant” and “none” are the two most popular categories selected. As glamorous as that may (not) sound, these “volunteer digital humanitarians,” as project leader Patrick Meier calls them, are performing a vital function in real-time rescue relief.

“It’s like sorting through a haystack,” Meier told NBC News. “You’ll only find a handful of needles, but you have to find those needles as quickly as possible.” Potentially, this is all information rescuers need right away. So far, volunteers have cleared a quarter million tweets, finding several thousand which indicate severe infrastructure damage, the need for immediate rescue or displaced populations. Since these tweets include the geolocation from where they were sent, each represents a dot on a map, which the United Nations is using to aid its rescue efforts. If enough dots end up in one concentrated area, you'd know that's where aid is desperately needed.

Monitoring social media can seem counter-intuitive following major disasters, which are often followed by a loss of cellphone service. In fact, Meier — whose day job is director of social innovation at Quatar Computing Research Institute (QCRI) — points to a 18.7 percent drop in tweets the Saturday following the typhoon. Yet when social media drops in specific areas of Philippines, which has one of the most active social media populations on the planet, first responders can immediately see that there are significant outages in that area that need to be addressed.

Monitoring tweets isn't as effective in the remote areas where the majority of the population doesn't use cellphones, let alone social media. Such was the case with the first use of MicroMappers in September, following the earthquake in Balochistan, Pakistan, where very little information was gained through Twitter.

Still, social media’s role in disaster recovery has greatly evolved since the Haiti earthquake in 2010, when it first played a major role in recovery efforts. Mostly, then, its purpose was raising money for the earthquake victims. Meier and others attempted to harness information shared on social media at that time. Yet despite what he describes as an "incredible surge of user-generated data" following the Haiti earthquake, the company Meier was working with at the time didn't have the technology that could handle the task.

"We were using a platform that was simply not meant for mapping over a 100 reports over a few days," he says. "We had literally hundreds of thousands of tweets, texts and emails, but we could only access about a dozen at a time." Though Meier says some valuable information came from the few hundred tweets vetted, "it was really brutal, a painful exercise.

MicroMapper, still in its test phase, is far from perfect, Meier admits, and he laments the few glitches, mostly on the user end. Since volunteers aren't obligated to register with MicroMappers, it's unclear how many people have already participated. Still, servers have crashed twice — once on Friday and once on Sunday — when CrowdCrafting's servers caved under the traffic MicroMappers attracted. The biggest problem, Meier says, is the occasional lag time. "You should click on a tweet, get another right away, click on an image, get another right away."

Instead, users may find themselves clicking repeatedly on the "not relevant" button before a tweet that reads "a massive thank u for those countries that helped phils to survive! #BangonPilipinas #YolandaPH" is replaced by new content that needs classifying. As Meier well knows, end users are easily distracted. If the Internet application is slow to load, people turn their attention elsewhere.

Even when things are going smoothly, they're not going as quickly as Meier would like. "Because of the server issues, we can only upload 1500 tweets and 1500 images at a time." Getting MicroMapper a server of its own is Meier's plan for the future.

"I want a server that can upload 100,000 tweets with 10,000 volunteers tagging them. That's a huge amount of information, fast."

Helen A.S. Popkin is deputy editor of Technology & Science at NBC News. You can find her on Twitter and/or Facebook.