Russian author and journalist Andrei Soldatov used to regard his country as the most digitally connected in Europe. These days, he can barely recognize the Russian internet.

Websites with the .ru domain have been online only intermittently since the invasion of Ukraine. U.S. tech companies such as Microsoft and Oracle have stopped selling software there. Many Russians can’t pay for the private networking apps they use to get around government censorship of sites such as Facebook, after Visa and Mastercard halted operations there.

“Russia is so dependent on online services. Now, these things are falling apart,” said Soldatov, author of the book “The Red Web,” about the Kremlin’s battles over online surveillance.

Russia is three weeks into a test that the internet has never seen before: A major economic and global power is nearly isolated online after international sanctions cut off many services from abroad and the Russian government clamped down harder on online speech and access inside its borders.

How the situation plays out is likely to shape the future of the internet, not only for everyday Russians but also for the collective understanding of what was supposed to be a global network, not one divided by a “digital iron curtain.”

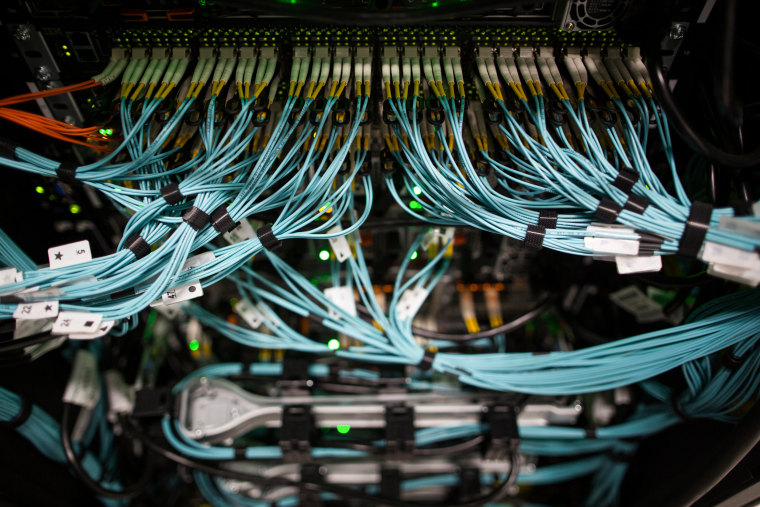

Experts said Russia is likely to turn to China to buy software and hardware products if it is cut off from U.S. and European products for too long. And Russia might have to scramble to find enough physical connections for its internet traffic if neighboring countries or non-Russian companies refuse traffic that runs through overland fiber optic cables.

The fiber optic cables and mobile networks that make up the guts of the internet have generally been apolitical, with a few exceptions, but the biggest land war in Europe in eight decades is challenging that idea.

“We didn’t have all those layers of politics interfering with the simple technical operation of these networks,” said Andrew Sullivan, the CEO of the Internet Society, a nonprofit organization formed in 1992 to strengthen the internet based on its original ideals, such as international cooperation and the free flow of information.

The Russian war in Ukraine is “obviously a very strong reason” in favor of some kind of response, Sullivan said, but he said he was worried about the precedent.

“The more we import those external concerns, the more likely it is that the network will be disrupted for other political reasons,” he said. “Once you open that door, there are a lot of reasons why you can imagine a network operator might disconnect.”

It’s a tension that’s always been part of the internet: U.S. military researchers created it, but it was California activists — including a former Grateful Dead lyricist — who built a mythology around it that the internet would be a universal, globalizing force for good.

Diplomatic maneuvers

Ukraine has lobbied in favor of Russia’s online isolation as one way to pressure President Vladimir Putin to cease his invasion. It even asked ICANN, a nonprofit organization that manages internet domains, to shut down .ru, a request that ICANN said went too far.

“ICANN has been built to ensure that the Internet works, not for its coordination role to be used to stop it from working,” CEO Göran Marby wrote in his response.

But the situation points toward a possible future internet divided up along national borders, in which each country’s government has what would amount to a customs office for imported internet content. Even before Russia invaded Ukraine, Russia and China were pushing a new, top-down internet protocol that would give internet providers the ability to block any website or app they choose.

“They want the ability to move to not one big global network but different networks where you can surveil your citizens more easily,” said Karen Kornbluh, a former U.S. ambassador to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development and a senior fellow at the German Marshall Fund, a nonprofit organization that supports stronger ties between the U.S. and Europe.

“In the longer term, Russia wants to be able to cut off access to Signal,” she said, referring to an app for secure and encrypted messaging.

The competing visions of the internet have been on display in a United Nations election campaign in which one candidate is American and another is Russian. At a conference in September, 193 countries will select the next chief of the U.N.’s telecom arm, the International Telecommunication Union, which is weighing the proposed internet protocol supported by Russia and China.

The Biden administration has also been adding diplomatic muscle to the international fight over the internet, announcing a new Bureau for Cyberspace and Digital Policy last year to be headed by an ambassador.

Concerns about the emergence of a “splinternet,” or a balkanization of the web, have been gaining momentum for other reasons the past few years. The Trump administration unsuccessfully sought to ban two popular Chinese apps, TikTok and WeChat, in 2020.

Social media’s foothold

For Russia, the isolation has been shockingly swift. Yandex, Russia’s biggest tech company and the operator of both the top Russian search engine and the top ride-hailing service, has said it is considering relocating 800 employees to Israel. Two directors have resigned, and the company has warned that it may not be able to pay its debts.

“It’s a sign of how desperate things have gotten,” Soldatov said in a phone interview from London. Yandex was the pride of Russia’s tech sector, he said. “Now it’s destroyed, and nobody knows what to do about it.”

Soldatov said many of the information technology specialists he knows in Russia are leaving for other countries or sending their children to live abroad, away from growing repression under Putin. The exodus of people overall is thought to be in the thousands.

The list of U.S. and European tech companies leaving Russia is long: Google halted ad sales, Netflix suspended service, Amazon cut off shipments, Apple pulled its products from its online Russian storefront, and other companies announced similar moves.

The big exception has been social media apps such as Facebook, Instagram and Twitter, which not only haven’t pulled out but are even fighting the Russian government to stay in as lifelines of uncensored information. YouTube, another forum for dissent, remains unblocked, but experts wonder for how long.

“Please do not cut off Russia from Facebook,” Soldatov said. “It’s the only space where you can have some sort of uncensored debate and you can talk about political news and you do not feel like you’ll be spied on by Russian security services.” (Apps for virtual private networks, or VPNs, allow people to disguise their locations and often evade government restrictions.)

It’s a role that helps to polish what has been a spotty record for social media’s relationship with democracy, and it’s a responsibility that U.S. tech companies have welcomed.

“Social media is bad for dictators,” Sheryl Sandberg, the chief operating officer of Facebook’s parent company, Meta, told CNBC at a conference last week.

Natalia Krapiva, the tech-legal counsel at Access Now, a nonprofit group that advocates for human rights online, said that whatever else happens to the Russian internet, Western powers should strive to ensure that Russians can read and hear different points of view — and not just via shortwave radio broadcasts.

“It’s not going to be helpful to isolate Russian citizens and leave them only with state propaganda that’s inciting them and urging them to hate Ukrainians,” Krapiva said.

“At the same time again, we’re hopeful that Russian civil society is resilient,” she said. “They have already been living under repressions, including digital repression, and during the past couple years it has really increased, and people have found ways to adapt.”

Above the fray?

Fights over government censorship aren’t new or unique to Russia. What’s different now is how geopolitics could affect the routing of internet traffic.

In general, a country and its local internet providers connect to the global internet by buying bandwidth wholesale from a handful of large corporations, paying by volume. Rostelecom, a Russian internet service provider, buys from about six companies, according to Kentik, a company that monitors internet traffic, and if one or more stopped selling, service could slow to a crawl depending on how much slack is in the system.

One wholesaler, Washington, D.C.-based Cogent Communications, has said it would stop selling service to Russia, while a second, Louisiana-based Lumen Technologies, has said it plans to follow suit.

“I’ve never seen this. I’ve never heard of this,” said Doug Madory, Kentik’s director of internet analysis. “Generally, the internet has been able to float above the fray. We’ve had wars, and most people in the industry feel like there’s a good reason to leave the internet alone.”

The difference this time, Madory said, appears to be the unity of the U.S. and European response, which has included other unprecedented actions, such as a partial ban from SWIFT, the global network for banks.

“This is sweeping and categorical — the amount of economic warfare to get the point across, to do everything short of shooting a bullet at a Russian soldier,” he said.

But Madory also said that, as of Monday, his company had seen little evidence in its traffic analysis of Cogent’s or Lumen’s cutting off Russian telecoms, raising the question of how far they would go in severing ties to Russia.

Mark Molzen, global issues director for Lumen, said in an email that the company was not providing any services in Russia and that its physical network there was disconnected. He added, however, that Lumen was servicing internet providers “outside Russia who are routing traffic into the country.”

Cogent said in an email that it had terminated services to customers in Russia to reduce the possibility that they “could be subverted and used for cyber attacks or other offensive activities.” But the company added: “As the Internet is by its nature a distributed system, traffic from Russian carriers may transit the Cogent network through an indirect connection via another provider.”

Not like Tonga

Regardless, Russia has connection points to its south and east that would keep it somewhat connected, even if the service is sluggish, said Nicole Starosielski, an associate professor of media, culture and communication at New York University.

“It’s not going to be Tonga,” she said, referring to the South Pacific country where an undersea volcanic eruption cut internet service entirely in December. It took five weeks before workers from a specialist ship were able to repair the undersea cable to Tonga.

“So many countries are so dependent on undersea cables and international internet traffic to function, and that’s much less true for Russia,” she said.

Putin has contemplated disconnecting Russia from the internet since at least 2014, and he has spent years pushing to make its “sovereign internet” more independent of other countries through homegrown software. Russia even has its own suite of Microsoft-style office software, but experts said the efforts have fallen far short of Putin’s goals.

A Russian official said last week the country had no plans to disconnect from the internet.

There are other problems for Russia, such as finding replacement switches, routers and other hardware. At least one bank began stockpiling equipment before sanctions hit. The typical life cycle for such parts is two to three years, said Paul Barford, a computer science professor at the University of Wisconsin.

“In the medium term, there could be a serious impact on their ability to maintain standard levels of communication capability,” he said.

Barford said Russia may look to buy Chinese replacements, but for now, the U.S. has threatened Chinese manufacturers with consequences if they step in. Taiwan, a major chip manufacturer, is complying with international sanctions against Russia.

Building internal internet controls like those in China to monitor and censor traffic may be tempting for the Russian government, experts said, but doing so would take years of effort and enormous resources and talent that Russia doesn’t have.

“Russia could evolve something like that if there’s a will to do that over time,” Barford said. “But that is very, very difficult to do, especially if people are not aligned behind it — if there are people who are in any way subversive.”