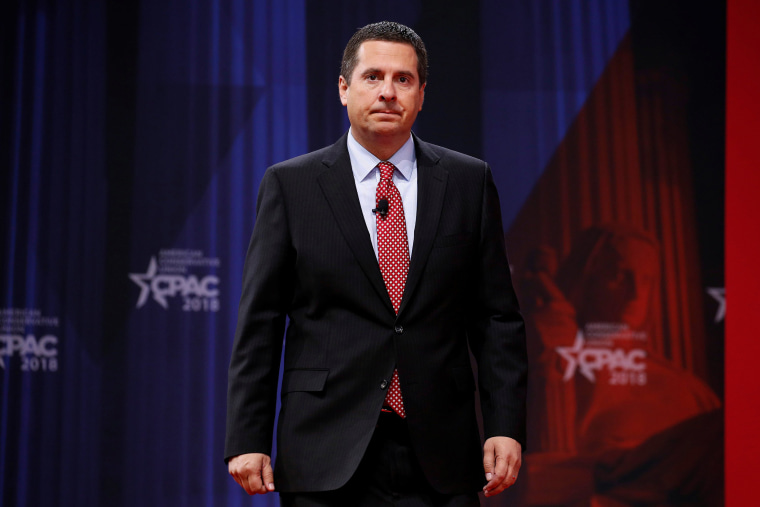

Rep. Devin Nunes, R-Calif., escalated the feud between conservatives and Twitter on Tuesday with a lawsuit accusing the company of defamation and negligence — two different allegations, one of which poses a more serious question for the social media platform and technology companies in general.

Nunes is claiming that Twitter negligently violated its terms of service when it allowed people onto its online “premises” to say false or disparaging things about him. He is seeking $250 million in damages due to “pain, insult, embarrassment, humiliation, emotional distress and mental suffering, and injury to [Nunes’] personal and professional reputations” brought on by what Twitter users said about him.

Defamation is an interesting legal matter to discuss, at least in theory, but suing for defamation is seldom profitable in reality.

Negligence may not sound as exciting as defamation, but this theory of liability quietly drives most successful civil litigation. Relatively easy to prove, it generally requires that the defendant show conduct that came up short of what can be expected, and that this shortcoming caused the plaintiff’s damages.

People use Twitter to say mean things about each other constantly. If Twitter were held liable for such statements, it is conceivable that the platform could be sued thousands of times every day. The same could be true of almost any social media company.

The primary reason that technology companies are not sued into oblivion is the existence of the Communications Decency Act, or CDA, and in particular Section 230, which states that providers of an interactive computer service shall not be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider. Ordinarily, a lawsuit like this is properly filed against the Twitter user or account (like “Devin Nunes’ Mom”) and not Twitter itself.

Section 230 and the CDA have become the targets of growing backlash against the idea that technology companies should not be held responsible for what is published on their platforms. Technology companies have voluntarily taken steps to moderate some content, such as extremism, conspiracy theories and fake news, but most personal insults and parodies are still allowed to flourish.

Section 230, however, isn’t necessarily bulletproof. At least one federal court has stressed that the statute does not “create a lawless no-man's-land on the internet.” That provides some basis for Nunes’ claim that Twitter has been negligent in keeping its platform from being used to spread damaging statements about him.

But a negligence claim against Twitter may still be precluded by the CDA. The test is whether the cause of action requires the court to treat Twitter as the publisher or speaker of content provided by another. In previous cases, courts have held that no amount of careful or creative can get around the CDA’s prohibition against holding Twitter liable as a publisher or speaker of another’s hateful rhetoric.

More simply, Twitter can’t be negligent if it is under no obligation at all to police the speech on its platform.

The defamation cause of action is interesting in that it invokes several constitutional principles, but it is even less viable as a cause of action.

Since at least the 16th century, courts have permitted actions for damage to a person’s reputation by the publication of false and defamatory statements. Defamation law was developed to allow plaintiffs to vindicate their good name, and to be compensated for harm caused by the false statements.

To bring a lawsuit for defamation in Virginia, as Nunes has, he needs to allege that a statement is both false and defamatory, and satisfy the following element: publication of an actionable statement with the requisite intent.

One of the legal hurdles that Nunes in his defamation claim centers on the sheer absurdity of the statements he alleges hurt him. There’s precedent in Virginia that may weaken his claims here.

In 1996, Sharon Yeagle, an assistant in the Student Affairs Office at Virginia Polytechnic Institute, sued the university's student newspaper for defamation and insulting words, after it published an article quoting Yeagle. Underneath the quote, the phrase “Director of Butt Licking” was printed under Yeagle’s name.

The trial court tossed the case, holding the offending phrase was “void of any literal meaning,” and that it didn’t convey any factual information about Yeagle. On appeal, the next court concluded the phrase was not defamatory as a matter of law.

To the extent the statements and images alleged by Nunes are similar to the “Director of Butt Licking” case, the defendants may have a shot at dismissing some of the defamation claims. The U.S. Supreme Court has protected language that is insulting, offensive or otherwise inappropriate, as long as it is just “rhetorical hyperbole.” Examples include the parody of public figures, a form of protected speech.

As a “public figure,” Nunes is governed by the higher burden established in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan in 1964. He is prohibited from recovering damages for defamation unless he proves that the statement was made with “actual malice.” He must demonstrate by clear and convincing evidence that the defendant either realized that the statements were false, or that the defendant subjectively entertained serious doubt as to the truth of the statement.

Defamation cases are always interesting to analyze because of the inherent constitutional issues involved. In practice, however, it’s not easy to win a defamation case, or prove a monetary value of the damage to one’s reputation.

For Nunes, it may not be legally feasible to do either.

Danny Cevallos is an MSNBC legal analyst. Follow @CevallosLaw on Twitter.