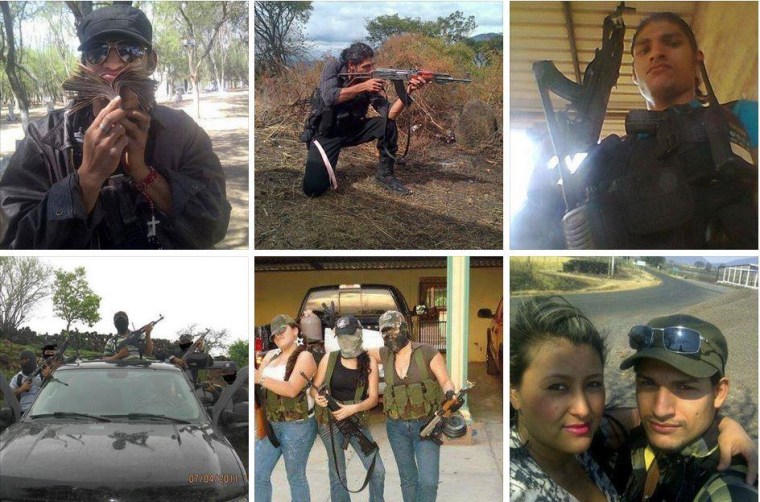

Take out the hostages, drugs and AK-47s, and the photos from Mexico’s most notorious drug cartels would not be that different from any other posts on social media.

But the brazen boasting doesn't necessarily make law enforcement's job any easier.

Sign up for top Technology news delivered direct to your inbox.

The tabloids went nuts last week for Claudia Ochoa Felix, who the Daily Beast and other publications reported may be connected to the powerful Sinaloa cartel. Her pouty expression and tight dresses on Instagram drew comparisons to Kim Kardashian — if the reality TV star spent a lot more time posing with firearms. (After the press attention, she denied involvement with the Sinaloa cartel and removed her photos from Instagram).

She is not the only one. Members of drug cartels have posted everything from selfies on Facebook to gruesome footage of executions on YouTube.

“You have seen an increase in this kind of thing as Mexico has become more wired,” Shannon O’Neil, a senior fellow in Latin American studies for the Council on Foreign Relations, told NBC News. “In general, the members of the drug cartels are younger. It’s a demographic that is very comfortable being online.”

In 2011, during the peak of Mexico’s drug violence, there were more homicides in Ciudad Juarez than there were casualties in Afghanistan. Those numbers dropped nationwide by 15 percent in 2013, mostly because smaller regional cartels were swallowed up by larger “criminal monopolies,” said David Shirk, director of the Justice in Mexico project at the University of San Diego.

For the most part, Shirk said, it’s not the cartel members at the top of the totem pole who are sharing information on social media.

“If they can drive around Ciudad Juarez with an AK-47 hanging on their door, why should they worry about posting on Twitter?"

“I don’t think El Chapo Guzmán has a Facebook page,” he said, referring to Joaquín Guzmán Loera, the former kingpin of the Sinaloa cartel who was captured in February.

When oversharing online could end in a jail sentence, why do some cartel members still use social media?

Some of it can be chalked up to young criminals just doing what young people everywhere do: brag about their lives on social media.

Other tweets and posts are more strategic. Criminal organizations use social networks to send messages to rival cartels, keep local citizens in line, and intimidate law enforcement, politicians and members of the media, experts said.

Last year, there was an international outcry when someone posted a graphic video on Facebook of a masked man, allegedly tied to the brutal Zetas cartel, beheading a woman.

"Well, gentleman, this is what happens to all those in the Gulf Cartel,” he said into the camera. “On behalf of Los Zetas."

Live Fast, Die Young

Cartels also use social media to recruit new members, especially the young and unemployed, George Grayson, a professor of Latin American politics at the College of William and Mary, told NBC News.

For young men struggling to make a living, Facebook posts filled with cash, gold-plated guns and designer clothing can be pretty tempting.

As the saying goes, “Better to be a prince for a year than a donkey for life." It's a proverb known by most drug cartel members, Grayson said, and social media only makes spreading that message easier.

Of course, even hardened criminals would rather not end up in jail. Law enforcement, like everyone else, does not need a warrant to follow an Instagram feed.

While some criminals might be reckless, many of them keep their posts anonymous, Shirk said, while others sometimes create fake accounts to taunt or implicate rivals.

More disturbing, however, is the prospect that they simply don't think they will be caught.

"The vast majority of the homicides over the last five or six years have gone unsolved," Shirk said. "Criminal impunity is a big problem in Mexico."

Police officers in Mexico make only about $9,000, according to the Council on Foreign Relations, which makes corruption a big problem. Fear keeps citizens and journalists from reporting crimes.

As O'Neil puts it, “If they can drive around Ciudad Juarez with an AK-47 hanging on their door, why should they worry about posting on Twitter?"