Financial brinksmanship in the Eastern Mediterranean seems an unlikely way for an obscure yet infamous virtual currency to become a household word, but that's what happened with the bitcoin. Over the last few weeks, bank turmoil in Cyprus and a frenzy of attention from the media have propelled the "crypto-currency" from the darkest corners of the Internet to the front page. But is this phenomenon a blip or a revolutionary new financial instrument?

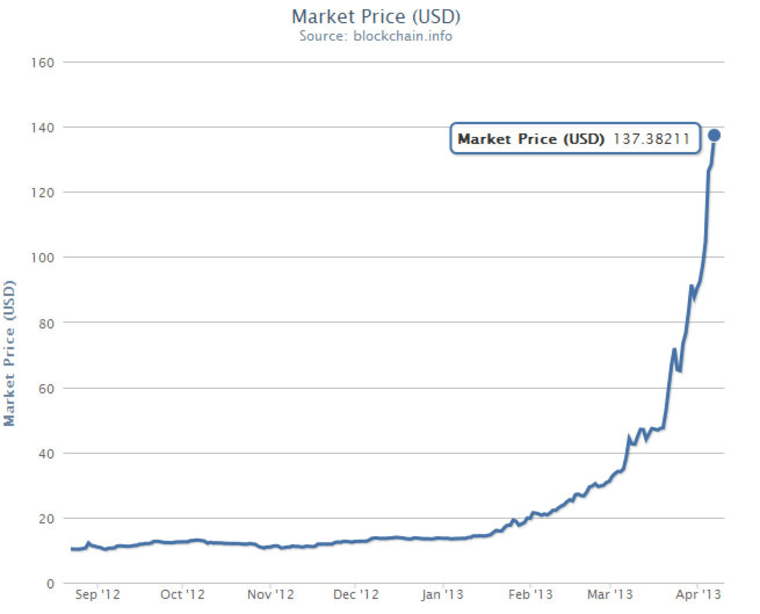

Existing only as numbers on the Internet, bitcoins are not tied to any retailer or company or bank. They have no real-world value other than what people agree to. And yet, at the time of this writing, each of the 11 million or so bitcoins in the world could be exchanged for just over $130 in real money — for a total value for the "currency" topping a billion dollars.

One way to look at it is like vintage baseball cards or comic books. There's a finite number of them out there, so as interest in owning them rises, the amount someone would pay for them goes up. And because there's a perceived value (an exchange rate), if someone is in the right market, that card or comic — or bitcoin — can be used to "buy" goods.

Bitcoin is accepted online for IT services and Web hosting, and a fair amount of tangible goods can be had for it, too. But just as you don't try using Action Comics #1 to pay for groceries, you can't use it just anywhere. This stuff isn't quite legal tender for all debts, public and private.

For years, bitcoin existed as nothing more than a meme among hackers and cryptologists, but the recent spotlight has caused it to be reevaluated.

"People are starting to realize they can now put their money in the cloud and access it anywhere, from any computer," Tony Gallippi, CEO of Bitpay, a company that facilitates bitcoin transactions with retailers, told NBC News.

Just two short months ago, one bitcoin hovered in the $10 to 15 range, and a $30 peak was considered ludicrously high. The surging valuation is indicative that, at the very least, people see it as more than just a nerdy hobby. Bitpay logged over $5 million worth of transactions in March alone, as people traded bitcoins for tangible items, mostly high-end electronics and precious metals.

But will you ever use bitcoin to pay for your pizza, or a new book on Amazon? Right now bitcoin is too volatile to be used for much other than highly geeky purposes. A few sites, deliberately courting the bleeding edge of Internet tech, accept bitcoin for services or products. But that isn't easy to do when a bitcoin may be worth $15 one month and $100 the next.

"The volatility that we are all witnessing stems from a lack of liquidity and market depth," Bitcoin Foundation secretary Jon Matonis told NBC News.

How (and why) bitcoin works

Bitcoin was created in 2009 by "Satoshi Nakamoto" — almost certainly a false name — in order to be anonymous currency, easy to use, self-regulating and free from any central authority.

Instead of relying on a government or bank issuer, the bitcoin system is entirely powered by users, transferred via unique, anonymous IDs. Whenever someone transfers bitcoins (or fractional bitcoins — they can be divided almost infinitely) from one "wallet" to another, that transaction is broadcast throughout the network, where it is confirmed by "nodes" that store the entire history of every bitcoin generated.

"Imagine if you've got a ledger somewhere that says who owns how much of some random commodity," explains Reuben Grinberg, finance lawyer who published a paper on legal issues surrounding bitcoin in 2011. "Instead of having the ledger held by some financial institution, it's maintained by this global network of computers. It's protected against the malfeasance of a single bad player."

But instead of the ledger containing names, it's just a list of accounts — pure numbers.

It's this anonymity that has led bitcoins to be associated with the purchase of illegal goods. The notorious "Silk Road" online shop — accessible only through the mysterious, encrypted worldwide "Tor" network — sells everything from marijuana to handguns. This gave many the impression that the bitcoin system was nothing but a handy way to break the law. (Of course, cash and a dark alley offer many of the same benefits.)

Bitcoin comes into its own

Anonymous currency available to anyone with an Internet connection would be useful in all manner of situations, but it was the events of the last few weeks that really began pulling Bitcoin's reputation out of the gutter.

First, the U.S. government acknowledged "decentralized virtual currencies" like the bitcoin by way of a branch of the treasury concerned with financial crimes. It's neither a positive or negative assessment, but it clarifies that bitcoin and its users are subject to existing laws regarding currency transmission and manipulation.

Second, a number of news sources reported a rush to buy bitcoins, made by panicked Cypriots looking to relocate their money from a failing bank system.

Regardless of the cause (and neither event seems to have been critical), the attention is real and has sparked debate about how one should consider bitcoin: Is it a commodity like gold? Is it more like a volatile stock? Is it like cash?

It's something new, says Grinberg. "It's sort of a hybrid of a couple different concepts. I can't hold it in my hand, it's not backed by the government, I can't pay my taxes with it." He thinks that it has some sort of future. — but the currency must settle down before the typical online shopper has anything to do with it. Grinberg says that could happen ... "far in the future, but not in the near term."

Devin Coldewey is a contributing writer for NBC News Digital. His personal website is coldewey.cc.