With today’s heightened awareness of identity politics, President Woodrow Wilson’s racism has become posthumously clear. This complicates Wilson’s legacy, especially when it comes to his contributions to the women’s suffrage movement.

On today’s anniversary of the signing of the 19th Amendment, which gave women the right to vote, it’s worth examining the events that led Wilson to support this amendment, for black women as well as white.

Because Wilson did not begin as a crusader for equality. He supported the status quo — until history backed him into a corner.

Wilson wasn’t enlightened about gender either. He labeled women who campaigned for suffrage “totally abhorrent.” But World War I changed him.

When Wilson won the White House in 1912, the women’s suffrage movement was going into its seventh decade. There was little likelihood of a constitutional amendment. But the thorniest obstacle was no longer sexism. It was racism.

As the first Southerner elected president since the Civil War, Wilson presided over the segregation of the federal government. He nodded at measures mimicking the Jim Crow laws that had sped across the South in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1896 decision, Plessy v. Ferguson, which enshrined the policy of separate but equal.

Wilson wasn’t enlightened about gender either. He labeled women who campaigned for suffrage “totally abhorrent.”

But World War I changed him. Wilson became the most highly placed advocate for universal suffrage until the ratification in 1920.

So what prompted this evolution? The Great War had brought many women into public service as nurses, ambulance drivers and telephone operators near the front lines. The trend was in favor of what newspapers called the “New Woman,” although male sentiment remained mixed.

Yet the day after Wilson announced the 14 Points, his platform for peace, he reversed his long-standing opposition to a federal suffrage amendment. He reminded surprised congressmen that Britain had enfranchised women, as had more than a dozen other wartime Allies.

“Are we alone to refuse to learn the lesson?” Wilson asked, “Are we alone to ask and take the utmost that our women can give — service and sacrifice of every kind — and still say we do not see what title that gives them?”

Wilson pleaded with Southern congressmen, who he knew risked their seats if they supported a federal amendment that trumped state election laws. He converted not a single one. Many denounced him.

Men of the U.S. Congress were split on whether women should vote. The one thing on which Congress agreed was that women’s suffrage would broaden the pool of African-American voters — with potentially ill effects.

Anyone who thinks America used to be better than it is now — or alternatively that we’ve made little progress — needs to dust off the “Congressional Record” from 1918 and 1919.

Anyone who thinks America used to be better than it is now — or alternatively that we’ve made little progress — needs to dust off the “Congressional Record” from 1918 and 1919. Opinion in Congress seemed unanimous that the 15th Amendment enfranchising black males had been a mistake.

Not one voice, for example, spoke in opposition when Sen. Ellison Smith of South Carolina said on the floor of Congress: “There is not a man in America today capable of exercising the functions of citizenship but that recognizes that amendment... jeopardized the civilization that you and I represent.”

Giving women the vote would compound that error, Sen. James Reed of Missouri argued. If, Reed said, the “dark sisters of the South” combined forces with Northern feminists, events worse than Reconstruction would follow.

Even Northern liberals like Sen. William Borah of Idaho opposed a federal amendment since no one had any intent of enforcing black male suffrage, much less black female suffrage. Why add more hypocrisy to the Constitution?

Unlike Congress, Wilson left unsaid that the 19th Amendment would improve the legal status of black women, though he knew it would.

White feminists also downplayed these consequences. Some were lifelong activists who embraced women of color and whose parents had crusaded for abolition. Others, however, were racists.

White feminists also downplayed these consequences. Some were lifelong activists who embraced women of color and whose parents had crusaded for abolition. Others, however, were racists, who hoped female voters would help repress people of color. All understood that the vote for black women was the most controversial aspect of their proposed legislation.

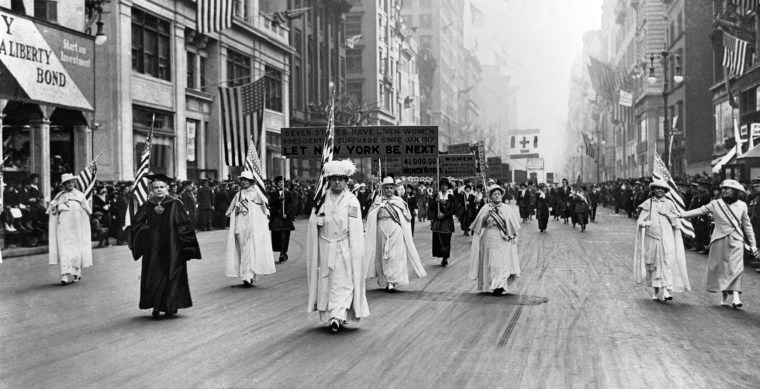

This was understandably humiliating for African-American feminists, who had been asked to walk at the back of the famous 1913 march on Washington to avoid further inflaming opinion against the amendment. Journalist Ida B. Wells defiantly slipped into the middle of the parade, but many others complied for the sake of the legislation.

Their courage at swallowing this vile pill attests to the importance they placed on the 19th Amendment. Each step advanced their struggle. Future generations would make the next strides.

Both Wilson and white suffrage leaders refused to openly confront the vicious beliefs of the era. But they also ultimately worked to subvert those beliefs.

Abolitionists had faced a similar dilemma in 1870. They could not win the vote for both women and newly freed male slaves. Appending female suffrage to the 15th Amendment would have made it too controversial. Abolitionists also acted expediently, and history has largely vindicated them. They told women to wait. Sexism was not as important as racism — a comparison bound to upset some.

In 1919, the priority and possibilities were reversed.

What’s the lesson to be learned here? We often rush to hang, draw, and quarter historical figures for their retrograde views. It’s easy — since most have feet of clay. Perhaps more relevant, though, is how far up the leg it goes.

Reserving our sharpest barbs for those who fall short of our ideals despite their accomplishments keeps Americans in mutual suspicion even now, instead of linked in common cause, appreciative of how far we’ve come and united on where we need to go. It’s important to remember that progress is not all or nothing. Because it’s forged by people, not angels.

We cannot ignore the misdeeds of past leaders, but Wilson’s record on suffrage is a reminder that humans can evolve. Even as he reinforced Jim Crow, Wilson gave black women new tools for fighting it.

Such is the halting, often contradictory nature of progress. With his feet of clay, Wilson walked the high road in championing the 19th Amendment.

Elizabeth Cobbs is Melbern Glasscock Chair in American History at Texas A&M, senior fellow at Stanford’s Hoover Institution and author of “The Hello Girls: America’s First Women Soldiers.”