My dad had his first heart attack the year I was born. After that, he was in and out of hospitals until he passed away when I was 10. During those years, my mother and I would sleep in the same bed so we didn’t have to be alone. In the morning, my mom would head to 16-hour shifts at work to afford our precarious middle-class lifestyle, while I would go off to school — a place that was horrifyingly underequipped to identify and address the symptoms of trauma I was exhibiting.

When I was withdrawn and disorganized after my dad passed, many of my teachers took it as a personal insult.

Around the time of my dad’s death, I started having mental and physical health issues from the stress: embarrassing gastrointestinal problems, sweating, dramatic weight loss, chronic asthma, anxiety. My teachers quickly labeled me “lazy” and “arrogant” for not participating in class enough, for missing forms and for struggling to turn big projects in on time — even though many of them knew my situation.

I was viciously bullied by my peers. I had poor hygiene because I was depressed — a common sign of trauma that my educators also observed but did not act on — and the other kids would whisper about how I was “gross” and “disgusting.”

By high school, I was suffering from undiagnosed attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, a genetic disorder that can be exacerbated by trauma. When I went to the school health office to seek help for what I know now were symptoms of my ADHD, they would express frustration with me and very little else. Teachers told me extensions “would be unfair to the other students,” and they chastised what they saw as a poor work ethic.

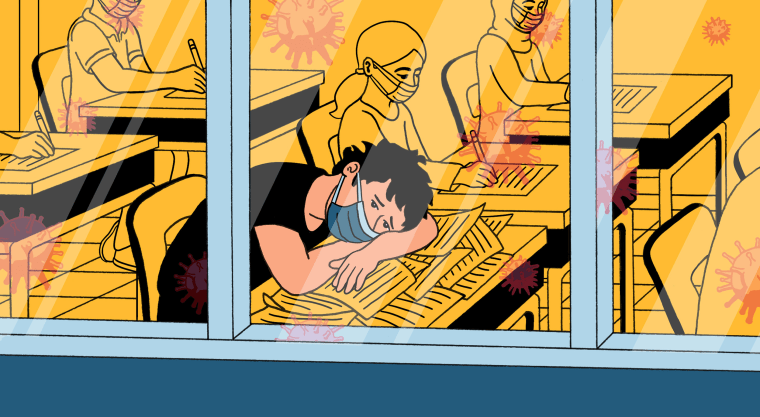

In essence, the education system penalized me for the trauma I experienced after my father died. With the collective losses of the pandemic, I’m worried that many more will suffer the same fate in school systems grossly ill-equipped to handle the needs of the students who will be suffering.

When I was withdrawn and disorganized after my dad passed, many of my teachers took it as a personal insult. I can only imagine how they will respond to the vulnerable children who experience losses due to Covid-19. In a nationwide survey of school social workers last summer, more than 3 in 4 reported most students at their schools needed serious mental health support in light of the pandemic.

Meanwhile, schools lack the necessary mental health providers. As of 2017, “up to 20 percent of children and youth experience a mental, emotional, or behavioral disorder. ... However, nearly half of all children with emotional or behavioral difficulties receive no mental health services,” according to studies cited by the American Institutes for Research. For the 2009-2010 school year, the National Association of School Psychologists found that only seven stateshad met the recommended ratio of students to school psychologists. As of 2017, those widespread shortages were projected to continue into 2025.

For those who do get mental health support, most receive it at school. There is a lot of responsibility on educators to catch mental health issues among students, and they often simply don’t have the resources. And as the Child Mind Institute noted, educators often don’t know the signs to look for, and students can hide their trauma as a way of avoiding rejection and shame. As child and adolescent psychiatrist Nancy Rappaport put it in the article, kids who have suffered a trauma “are masters at making sure you do not see them bleed.”

While teachers are frequently left to fill in the gaps, they often have to do so with very little training. One teacher wrote in The Atlantic, “Over the years, my students have entrusted me with their most harrowing moments: psychotic hallucinations, sexual molestation, physical abuse, substance abuse, HIV exposures.” Yet she reported being “horribly unprepared” and thus “failed to secure the services” her students needed.

Educators right now are also struggling with mental health problems themselves. With both teachers and students suffering psychologically, school, community and government help is needed that much more.

If one good thing can come from Covid-19, it can be a push to do better. Schools must ask themselves how they will prevent my story from being the experience of thousands of other students. We have long known that there are not enough psychologists in schools, that there are not enough mental health certified teachers and that we are not taking all the steps national mental health organizations advocate. That has to end.

Educators are responsible for molding and shaping young minds. Yet we spend very little time informing them how young minds work and how to tend to the most vulnerable ones around them. Now is the time to educate them on what to do and give them the tools they need, so they can best educate those in their care.