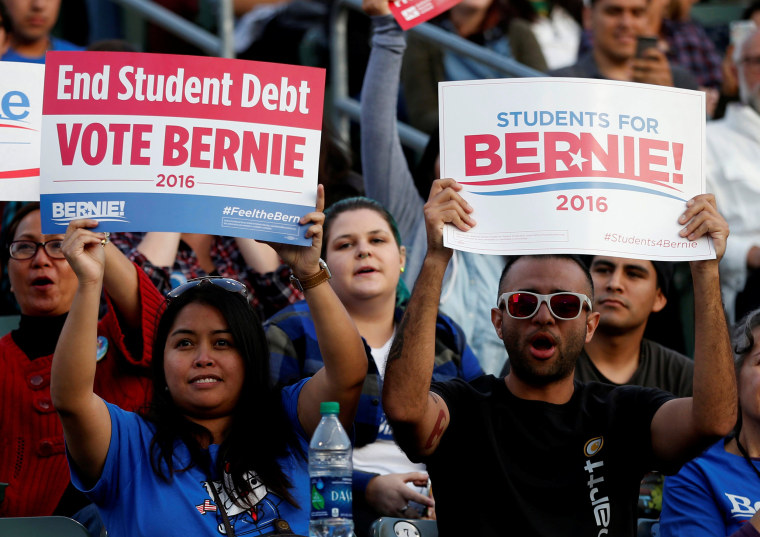

The amount of student debt in the United States is approaching $1.5 trillion, and that staggering sum has prompted certain Democratic presidential candidates to propose increasingly expansive — and expensive — plans to forgive at least a portion of students’ loans. The latest is Bernie Sanders, who on Monday unveiled a plan to forgive all student debt.

Yet Sanders’ plan, like the one Elizabeth Warren announced in April, doesn’t address the real problem that has to be tackled to make college affordable in the long term: the cost of providing an education. Until these costs are dealt with — a considerably more complicated and politically fraught undertaking than college loan forgiveness — student debt relief will be a temporary fix.

We need to bring down the cost of education itself, rather than merely compensate students for their soaring tuition prices.

And that temporary fix is pricey. Warren’s plan forgives up to $50,000 in student loans (the typical student has $30,000 or so in debt after graduating with a bachelor’s degree) to the tune of $640 billion. Sanders’ plan would forgive all student debt regardless of income level or amount of debt, which means coming up with the $1.5 trillion in outstanding payments.

To help current and future students, the Warren and Sanders plans include tuition-free public college systems, as well as some additional money to help students pay for textbooks and living expenses. But as a researcher who studies higher education finance, I am skeptical that tuition-free college plans will be any more permanent a solution than debt relief. We need to bring down the cost of education itself, rather than merely compensate students for their soaring tuition prices.

Since the late 1980s, tuition and fees have more than doubled after adjusting for inflation. Household income has experienced a 10 percent increase over the same time. State and federal governments, as well as colleges, have tried to offset some of this increase in prices by providing $110 billion in scholarships each year. But this money has not been enough to keep up with the hikes, leading to ever-rising student debt burdens. Worse yet, these tuition and fee charges don’t provide the amount of money needed to actually educate a student — and that cost of a college education, different from the price tag charged for it, continues to rise faster than inflation or family incomes.

A primary driver of this problem is the fact that higher education is a labor-intensive industry, as students like being taught by professors in small classes. Unlike some other fields with highly educated professionals, such as investment banking, technology has done relatively little to reduce the need for one-on-one interactions. Online classes and artificial intelligence may help reduce costs around the edges, but there is no equivalent to automated stock market trading in higher education. Health care is in a similar place, and unsurprisingly health care costs are one of the few areas keeping up with higher education’s cost increases.

Because a majority of higher education costs involve people, rising health care costs are actually a double whammy. Health care and retirement expenses continue to grow quickly, especially in states that cut corners on retirement plan funding for generations. Colleges’ efforts to both fix crumbling Cold War-era buildings that need replacement and build shiny new facilities to attract students also contribute to rising costs.

Most “free” college proposals do not attempt to address these rising costs because the solution is difficult, and much less politically appealing than the slogan of free college and erased debt.

The federal government could afford to give students tuition-free options much more easily if it capped faculty and administrator salaries and health benefits as a condition for federal funding, required all classes to have at least 100 students, and mandated a return to the cinder-block classrooms and dormitories that were popular in the 1950s. But these options would not be popular with students, and would likely result in the politically toxic and socially undesirable effect of wealthier families choosing to attend better-funded private institutions while lower-income families attend the less-resourced public colleges.

Any long-term promises for debt relief and free college made now could also boomerang on students down the road.

Any long-term promises for debt relief and free college made now could also boomerang on students down the road; as federal budget deficits continue to increase, expect college tuition funding to get scaled back by Congress and the White House.

States’ experiences with such policies only reinforce my skepticism. Georgia introduced a wildly popular HOPE scholarship program in the early 1990s that covered tuition and fees for all students at state schools. However, the state stopped covering fees during the Great Recession in the 2000s and encouraged colleges to charge fees in place of tuition. New York’s much-discussed Excelsior Scholarship program to attend state schools tuition-free includes a whole host of eligibility requirements and also does not cover about $2,500 per year in required fees.

Student debt relief and free college programs are politically popular among young, college-educated voters — a key portion of the Democratic Party’s electoral base. But in order to make these programs sustainable, something needs to be done about the cost of providing a college education. So far, nobody is taking on that challenge.