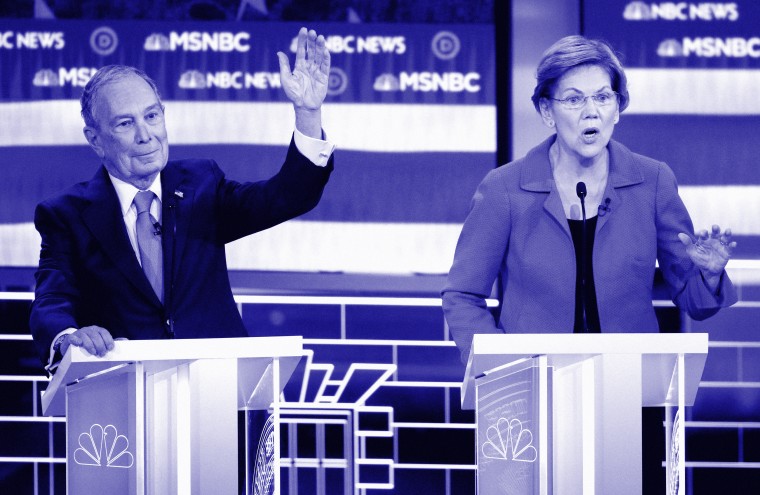

During the Democratic presidential candidate debate on Wednesday night, Mayor Michael Bloomberg exhibited a breathtaking failure to understand the cultural shift that has taken place as a result of the #MeToo movement. No longer can employers ignore or minimize sexual harassment or assault of women in the workplace.

When confronted with questions about his use of nondisclosure agreements in settling claims of sexual harassment and workplace discrimination brought by employees against his media empire, Bloomberg exhibited a kneejerk defense of NDAs, insisting that such agreements are “made consensually.”

The revelations and allegations about Harvey Weinstein, Roger Ailes and Bill O’Reilly, to name but a few, clearly demonstrate that women are often coerced into agreeing to nondisclosure agreements that carry with them severe financial penalties for those who choose to speak out. Indeed, NDAs have been used for decades by employers as an instrument to silence victims of sexual harassment and to protect serial sexual harassers.

Rather than demonstrating a commitment to transparency and accountability on these issues at Wednesday’s debate, Bloomberg doubled down. He steadfastly refused to release women from their NDAs, which could contain onerous terms. And he justified his refusal by shifting the blame to the women who came forward with allegations of mistreatment, asserting that it is the women who “wanted to keep it quiet for everybody’s interests.” This justification is disingenuous and tone-deaf.

Friday, after intense blowback from his comments during the debate, Bloomberg appeared to change his position and agreed that three women who had accused him personally of wrongdoing could be released from their nondisclosure agreements. But this gesture doesn’t go far enough.

His move doesn’t address the many women who may have endured harassment and abuse by others at his company under his watch and will remain bound by NDAs, whether they want to be or not. It also does not solve the problem of the pre-employment NDAs that Bloomberg campaign workers have received as a condition of employment. NDAs as a condition of employment are categorically wrong because they chill the ability of women to report harassment or abuse.

A complete ban on NDAs as part of settlement agreements, however, would not eradicate sexual harassment, nor are they always in the best interest of women. Many women — indeed the vast majority of women we have represented in sexual harassment and sexual violence matters — wish to preserve their privacy and keep the details of trauma and mistreatment they have endured confidential. So women must be given the choice.

Bloomberg and those running other large corporations should understand that choice is the critical factor when looking at this issue. Women who entered NDAs before the #MeToo movement might make a different decision today. Times have changed.

Women should be allowed to determine their own fate and not be coerced into something that makes them feel even more vulnerable or at risk. NDAs voluntarily entered into can be important for women to achieve closure after experiencing sexual harassment and to receive just compensation. In nearly all settlements of civil claims, confidentiality provisions are an important bargaining chip for plaintiffs, and a complete ban on NDAs in cases of sexual harassment would lead many employers to refuse to enter into negotiations at all. And where negotiations did occur, victims of sexual harassment and abuse would find themselves with less bargaining power than other complainants, magnifying the imbalance that lies at the heart of sexual harassment itself.

NDAs voluntarily entered into can be important for women to achieve closure after experiencing sexual harassment and to receive just compensation.

We do not want to leave women with less leverage and fewer options to deal with a terrible experience. Banning NDAs would also deny victims of sexual harassment an important source of autonomy and protection after a degrading experience. For many women, having a legal guarantee that their harasser or co-workers will not be able to share painful, and often intimate, details about past events has significant value. In voluntarily entering into such agreements, women are taking rational steps to protect their privacy and reputations and avoid further trauma.

While #MeToo has been a tremendous platform for disclosure, it is also essential that society honor the wishes of women who do not want their stories to be told. Eventually we hope to see a cultural shift that makes sexual harassment and the need for NDAs the exception and not the rule. Until that time, however, women must have agency when making decisions about disclosure.

For this reason, Bloomberg needs to release all women — not just three — who are bound by NDAs if they wish to come forward. We have witnessed through the #MeToo movement the power of women coming forward as a vehicle for individual healing and empowerment but also as a powerful tool for social change. Bloomberg would do well to recognize this.