Suddenly, everyone wants to apologize to Britney Spears.

The new documentary "Framing Britney Spears" has catapulted the pop star back into the spotlight, highlighting those who treated the singer badly and sparking what feels like a mass reckoning, a decade and a half later.

The film showed Spears as a 24-year-old divorced mother of two with postpartum depression who was stalked by paparazzi and tabloids trying to profit from her mental health problems. The bad press led to her father's contested conservatorship of her estate and the #FreeBritney movement by fans who blame her mistreatment on sexism and outdated patriarchal laws.

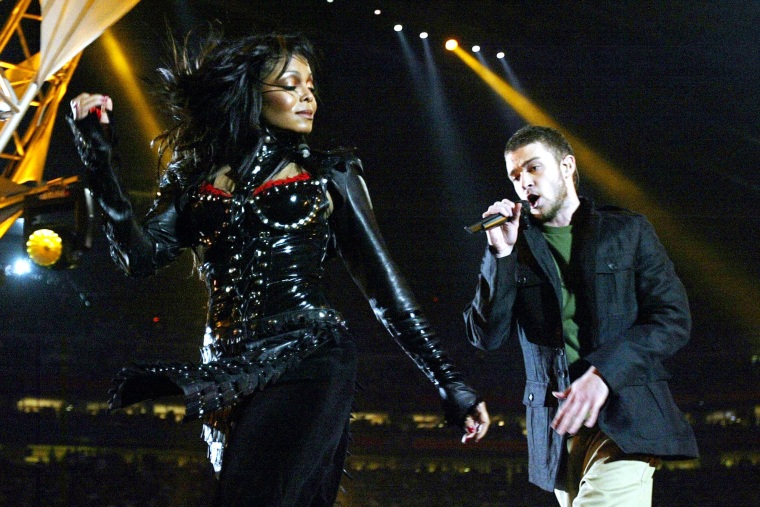

Comedian Sarah Silverman, for example, has come forward to publicly express regret for her MTV joke that Spears' children were "the most adorable mistakes." Glamour magazine posted: "We're sorry Britney. ... We are all to blame for what happened." Perhaps most notably, Spears' ex-boyfriend Justin Timberlake apologized on Instagram for his horrible behavior, atoning for telling a reporter they'd slept together, as well as for joking about Janet Jackson's Super Bowl wardrobe malfunction. "I fell short," he said, "and benefitted from a system that condones misogyny and racism."

Critics in the Chicago Tribune and USA Today have called this belated show of remorse, obviously inspired by the #MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements, too little, too late. But even the delayed confession of sins and desire for repentance can be healing. I learned this after my own falling-out with a respected mentor, a father figure for 15 years. His betrayal inspired my new book, "The Forgiveness Tour," in which I interviewed religious leaders, therapists and people who suffered wrongs never atoned for.

When my mentor finally contacted me to come clean, I wondered whether his motives were sincere. What if he was just trying to avoid a public scene?

I consulted Connecticut psychiatrist Vatsal Thakkar, who said: "Things can coexist. There can be many reasons for an apology." Questioned about the pop culture ramifications, he continued: "In the case of Timberlake, even if the motivation for his public apology is to save face or protect his career, that doesn't necessarily negate the good of his message. If you've done harm, silence implies it's not important or the victim should just get over it. Yet someone with a high public stature apologizing can create a new norm. It acknowledges failures, validates pain, helps victims feel vindicated and move on."

That's probably why governments have offered long-belated apologies years after their crimes. Even though they may feel late, they carry symbolic weight. America issued official remorse for interning Japanese Americans during World War II only in 1988 — 42 years after the camps closed — and South African apartheid leader F.W. de Klerk didn't atone for 46 years of racism until 1996. Of course, these apologies, too, can be greeted with heavy skepticism. When we were discussing East Germany's apology to Jews for the Holocaust in 1990, a Jewish colleague of mine noted that the contrition didn't match the massiveness of the crime. He joked that it felt as if authorities were saying, "Oops, massacred 6 million of your people. My bad."

Obviously, there's a difference between the way Britney Spears and Janet Jackson were treated and institutionalized, state-sanctioned violence.

Obviously, there's a difference between the way Britney Spears and Janet Jackson were treated and institutionalized, state-sanctioned racism, discrimination and violence. But even on a more personal level, reckoning, reconciliation and forgiving — while a slow process — can have a strong positive impact. Brooklyn journalist Deborah Copaken was date-raped in 1988 before her college graduation. Decades later, she told her rapist in a letter how hard it had been for her to overcome. Now sober, he called to apologize. He kept saying "I'm so sorry," she wrote in The Atlantic, as "thirty years of pain and grief fell out me."

"Hurt and guilt can last a long time. It's worth it to try to mend a damaged relationship or to repair harm, especially if you can make restitution or take measures to prevent it from recurring," said Boston psychologist Molly Howes, author of "A Good Apology." "The pandemic has given many people time to reconsider old regrets, relationships that ended badly and unresolved conflicts." The only exception? "Don't reach out directly when the person you hurt has asked you to stay away or if it would inflict further damage," Howes added.

During an eight-year estrangement from her son, a Florida widow I interviewed sent him cards and letters, sharing remorse for her divorce and everything that hurt him during his childhood. Her attempts worked; today they're closer than ever. Contrary to the old "Love Story" line "Love means never having to say you're sorry," love often requires saying it repeatedly — and belatedly.

Since many people are not ready to forgive on the spot, Jewish law actually requires a person to ask heartfelt forgiveness three times, with three witnesses, Michigan rabbi Joseph Krakoff explained. Then, if the injured party won't forgive, the sinner is forgiven and the non-forgiver has to seek forgiveness for not forgiving. "After expressing regret, keep your heart open," Rabbi Krakoff advised. "Forgiveness might come, though not immediately."

"I've seen patients grapple with regret, guilt and forgiving for many years after someone's gone," Connecticut psychiatrist Thakkar said. "But even apologizing — or forgiving — posthumously can be powerful. You can write a letter you show to someone close to the deceased or share with a therapist. Or read it aloud at the gravesite."

Long after I'd missed my grandfather's funeral (because I hated how he'd insulted my father) I told my dad I regretted skipping it. That opened the floodgates, resulting in an emotional tête-á-tête that mended a lifetime of misunderstandings before I lost him three years ago.

For her part, Janet Jackson posted a heartfelt, tearful video to her fans that many took as a response, at least in part, to Timberlake's apology. Britney Spears has yet to offer official forgiveness directly, but her inner circle seems to appreciate the change of tide. Her mother, Lynne Spears, "liked" social media posts from the #FreeBritney movement.

Hopefully, Spears will one day get the apology from her father that she seems to so richly deserve. And it wouldn't hurt Timberlake to make a big donation to #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, putting his money where his mea culpa is.