Many of the parents I know have done a lot to help their children get the best education possible, from collecting other people's cans off the street for the redemption credits to pay for extra tutoring, to working second and third jobs to afford for private school tuition, to renting an expensive studio apartment to accommodate their family of four so they could live in the district with the best schools. As parents, we sacrifice, particularly for the education we see as key to our children's adult success — and we do so willingly.

To that end, many of us can almost understand the alleged decision of some parents to participate in an illegal scheme to ensure a spot at an elite school for their children. If we could’ve done that, we've thought to ourselves, we would’ve.

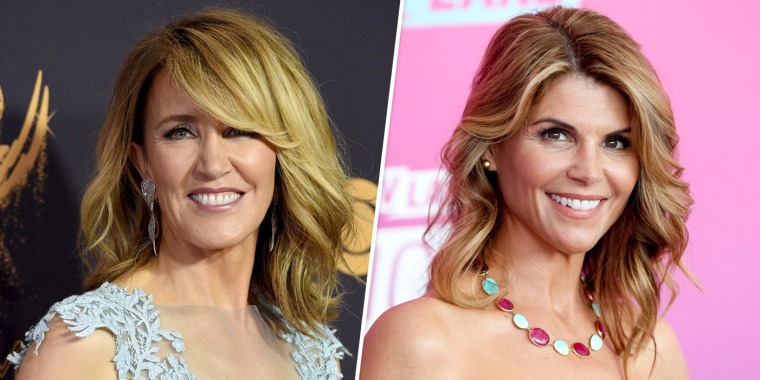

The reactions to the college admissions scandal — the Justice Department announced charges against a group of approximately 30 parents allegedly bribing exam proctors and school officials to ensure their children spots at Yale, Stanford, the University of Southern California and others — certainly varied from anger to Schadenfreude to marvel at how foolish some of the parents clearly were.

But among fellow parents, the reactions quickly shifted from disgust to something that more closely resembled empathy. It shifted from being mad about the greediness of wealthy parents to the latent guilt some of us feel for the decisions we have to make in order to get our children in “good schools."

The only problem is that most of us are not really in the same situation at all. The parents who can spend a reported $1.2 million to buy their child a seat in a particular elite university likely don’t have to worry about the scrounging to (hopefully) afford rent in a good school district, let alone rent that is inflated by the reputed quality of those schools. They're not buying rubber gloves and digging through their neighbors' recycling bags for Coke cans to bring to the grocery store for five cents a pop. They're not sleeping in their cars because there's not any time between jobs to go home and get in a nap.

There is sacrifice, and then there is bribing your kids' way into college in an intergenerational transfer of greed. And that greed has long affected the way local school districts are funded and supported for generations.

This conversation around housing hunting by school district has always essentially accepted the idea that some schools are academically good for their students and others simply aren’t. It has often informed parents' decisions about where to live when they decide to have children, if they can afford to make decisions based on more than their income and employment status at all.

But what we ought to start asking is why every school in America today isn't a “good school.” Why does acquiring a good education require a different housing strategy? Why does anybody have to abandon a community where they've lived in order to find good, quality, well-supported education for the children they have?

The fact that not all schools provide an education that qualifies students for success in life is a question of policy. And, like many old and outdated policies in this country, it is deeply rooted in racism.

Schools are funded largely based on the property value of the homes in the district — and district lines are frequently drawn based on the populations the planning departments wanted to include and exclude explicitly. For generations, this kind of behavior has resulted in predominately black neighborhoods being excluded from otherwise predominately white districts.

Furthermore, racism in homeownership choices and mortgage lending practices has affected not only who could buy property in predominately black communities, but also the desirability of these communities, which dramatically affects property values.

When schools are funded based on property taxes, and property values are suppressed by racism and racist policies in lending, schools in those communities never get the support and resources necessary to be seen as “good schools,” and further limits the ability of the community to grow into what it has the capacity to be. It is a painfully cyclical process that simultaneously feeds into itself and still manages to send itself spiraling down the drain.

It also further increases the lengths to which parents are willing to go in order to gain access to the “good schools.” Parents like Kelley Williams-Bolar, a woman who used her father’s address to send her daughters to his school district instead of her own. She saw the risk of lying as a worthwhile one in order to ensure that her children’s needs were met. At the same time, that very school district sent a private investigator after Williams-Bolar to prove that she was lying about her residency; she was charged with a felony.

It shouldn’t be so hard to raise children and give them a good elementary and secondary education; it shouldn’t require that degree of desperation. And yet we see it constantly.

So even though we parents might feel a tinge of empathy for people who seemingly went to great lengths to ensure the success of their children, we should remind ourselves that their so-called sacrifices were an effort to bypass the even minimal barriers of educational attainment that elite schools require of the rest of us, allegedly by way of bribes. It was greed for their children, not sacrifice: Sacrifice is a selfless act, but greed is about self-fulfillment. Positioning self-fulfillment as a righteous act is a terrible lesson to teach any of our children — though it's increasingly clear it was a lesson these parents' children learned long before they applied to college.