Emily R. is a first-generation college student at Northern Virginia Community College. Outside of school, she works in the hospitality industry while raising her 4-year-old son and rents a two-bedroom apartment with five other people. Emily's carefully balanced world began to topple as COVID-19 changed the world: In March, her son's day care closed, her work hours were cut and her classes were moved online. Struggling to pay rent, Emily applied for emergency funds from her school but was denied.

Student parents continue to be a mere afterthought in the field of higher education.

As institutions of higher education strategize about how to reopen their campuses, it is imperative that they address gaping holes in student support programs — holes that have long existed, but are now exacerbated by the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. That means colleges and universities must start tailoring their efforts to support the whole student. For students like Emily, that includes her son.

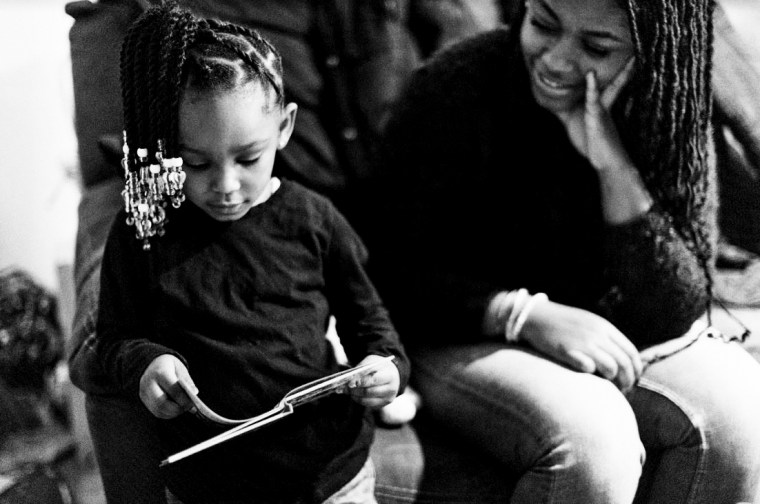

Fortunately, Emily is a Generation Hope Scholar, a status bestowed by a nonprofit focused on college completion and early childhood success for teen parents in the Washington, D.C.-area, and she received organizational funds to help pay rent and other bills. But Emily is just one of an estimated 4.3 million parenting students.

In fact, at least 1 in 5 college students is parenting a child while enrolled in classes, with students of color, female-identified students and first-generation students more likely to parent during college. Despite these numbers, student parents continue to be a mere afterthought in the field of higher education.

Studies show that a college degree for these students is transformational, not only for them but also for their children. That's because it affects both a parent's employment opportunities and lifetime earnings potential, and a child's chances for achieving academic and career success. But all too many college students juggling parenting do not graduate, despite typically having higher GPAs than their nonparenting peers. In fact, 52 percent leave college without a degree, compared to 32 percent of students without children.

In a just-released study, 53 percent of parenting students experienced food insecurity, 68 percent experienced housing insecurity, and 17 percent experienced homelessness.

That success versus completion gap is largely because these students have unique needs that go unaddressed. In a just-released study, the Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice — a research center at Temple University — found that 53 percent of parenting students had experienced food insecurity, 68 percent had experienced housing insecurity and 17 percent had experienced homelessness. And that was before the pandemic caused many to lose their jobs and sent their children home from school, day care and aftercare programs.

The high cost of child care plays a large role in undermining student parent success. The Hope Center survey found that nearly 4 in 5 students who used child care couldn't afford it. It seems intuitive, but bears repeating: Students for whom child care is unaffordable are more likely to miss class and/or work in order to care for their kids. But there are more insidious reasons as well, like insufficient transparency or clarity about kids-on-campus policies which also may play a role. In another national survey of student parents conducted February-April 2020 by Generation Hope, nearly 60 percent of respondents did not know if there was a campus policy on bringing their children to class. More than 60 percent missed at least one day of class in their last semester because of a lack of child care.

These are the realities for students with children. They have to juggle college responsibilities with parenting, scraping by just to afford rent without much, or any, support from their schools. Generation Hope's survey found that nearly half of all respondents felt disconnected from their college community, and 40 percent indicated that they felt isolated on campus. It was challenging before, but now the distancing measures put in place by COVID-19 are exacerbating these hurdles and pushing student parents to the brink.

For colleges and universities committed to student success and improving completion rates, Emily's scenario and the overall data on student parents should be cautionary. Yes, student parents are tenacious. But colleges are asking already beyond-stretched student parents to weather COVID-19 without proactive support, leaving them vulnerable to falling behind in class, not returning in the fall, and jeopardizing their degree.

The good news is there are tangible actions schools can and should take that would not only provide relief to student parents, but also signal that they are valued by their institutions.

The good news is there are tangible actions schools can and should take that would not only provide relief to student parents, but also signal that they are valued by their institutions.

To start, we know that what doesn't get measured doesn't get attention. That's why institutions must begin tracking and collecting data on the parenting status of their students. Administrators need to know these numbers if they are to better understand the student parent experience.

Colleges should also institute family-friendly policies, like priority registration for classes for student parents, giving them the chance to choose class times to suit family needs, or children-on-campus policies, and make sure they are clearly communicated to all students. Designating dedicated staff to work with parenting students will not only help provide the direct support they need, but also ensure their voices and experiences are incorporated when amending and creating school policies.

But it's not just practical needs schools need to address. Identifying ways to better engage and include parenting students in campus life is critical. In our work we have seen better engagement lends itself to increased likelihood of completion. In Generation Hope's survey, more than a third of respondents did not see any family-friendly characteristics (such as changing tables, lactation rooms or playgrounds) on their campuses, reflecting the lack of physical space that exists on campuses to accommodate parenting students. While parenting students are limited in their free time, they still want — and deserve — to feel included in their college community just as their nonparenting peers.

Finally, colleges and universities must incorporate student parent needs into their government relations work. As we face the fallout from COVID-19, institutions need to identify student parents as a priority group when awarding emergency assistance from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act. Schools need to step up and do what is long overdue: advocate for states to help low-income student parents and waive Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program work requirements and allow students to meet their Temporary Assistance for Needy Families work requirement by attending college. And, to remove a significant barrier to completion for parenting students, colleges and universities must advocate for increased affordable child care funds.

Strategies to ensure scholars are able to survive the uncertainty of the pandemic and still complete their degree will require institutions to evolve to fit the reality of today's students. As Emily recently explained, "If colleges would support student parents and say 'we get it,' that would impact everything — grades, attendance, even other teen parents like me believing higher education is possible."