The 400th anniversary of the introduction of slavery to the Jamestown Colony, coupled with a tremendous endeavor from The New York Times called the “1619 Project,” has fueled the ongoing national debate over reparations. It is proof of William Faulkner’s insight: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” As the 2020 Democratic primary heats up, the legacy of slavery has also been a hot topic among 2020 presidential candidates. Some, like Sens. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts and Cory Booker of New Jersey and the author Marianne Williamson, support monetary payments, while others, like Mayor Pete Buttigieg of South Bend, Indiana, advocate new policies to address persistent racial inequities.

The fact that the debate is intensifying 154 years after the Civil War ended is a sign of moral turbulence that must be addressed. According to the Bible, “whoever conceals his transgressions will not prosper, but he who confesses and forsakes them will obtain mercy.” While public policy is certainly part of it, the conversations Americans are having right now are about more than politics: They are rooted in religious and moral traditions surrounding the meaning and necessity of contrition.

The fact that the debate is intensifying 154 years after the Civil War ended is a sign of moral turbulence that must be addressed.

This is not the first time Congress has recently attempted to address the issue of slavery. The House in 2008 and the Senate in 2009 put forward resolutions apologizing for slavery, but no joint bill passed. Since 1989, prominent African American representatives have proposed larger bills to address America’s “original sin.” While these proposals focus on reparations, it is noteworthy that they start with calls for a formal national apology.

Indeed, competing calculations of reparations range from an apparently serious estimate of zero to $6 trillion to more than $14 trillion. But the question of an apology stands on its own and should come first.

Apologizing is not just about making the wronged party feel better or whole. It is an act of self-correction: The apologizer is declaring that in spite of what was done, they are no longer that type of person — or nation. They are better than that. In the Roman Catholic sacrament of penance, for example, genuine contrition is a necessary precursor to reconciliation with God.

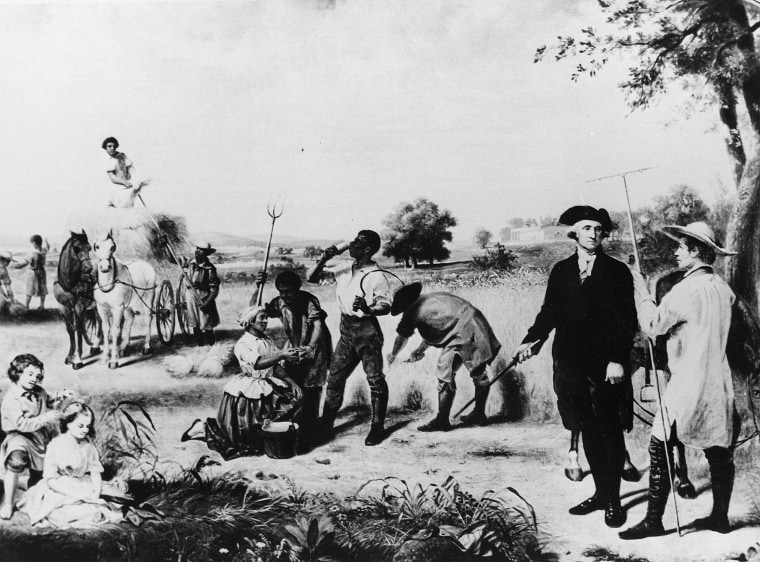

This idea of making amends is not only a religious tenet but a psychological truth. Because slavery was a state-sanctioned institution — effectively written into Article 1 of the U.S. Constitution — it makes sense that the federal government should be held to account. The United States has acknowledged the injustice in a variety of ways — waging a Civil War, emancipating slaves, amending the Constitution and enacting statutes to provide citizenship, equal protection and civil rights. As a nation, however, we have never apologized. This is a deep moral failing, compounded over decades.

The point is made more acute because the United States has rightly apologized to other wronged groups of fellow Americans: the World War II Japanese internees, Hawaiians, Native Americans and the Tuskegee syphilis study victims. In all these cases, Washington engaged in dehumanizing behavior toward a group of people in the name of the United States.

In 1860, there were more than 3.9 million slaves in a total U.S. population of 31 million. If any national bad deed deserves an apology, the scale of this atrocity demands it.

In 1860, there were more than 3.9 million slaves in a total U.S. population of 31 million. If any national bad deed deserves an apology, the scale of this atrocity demands it.

President Bill Clinton described the principle for official apology in 1997, when he spoke to the Tuskegee victims: “It is not only in remembering that shameful past that we can make amends and repair our nation, but it is in remembering that past that we can build a better present and a better future.”

Other countries have made historic apologies to wronged domestic groups. Australia set a strong example in 2008, when then-Prime Minister Kevin Rudd apologized in Parliament for what was done to the country’s indigenous people.

Religious congregations have taken similar steps. The Episcopalian Church formally apologized in 2008 for the “sin and fundamental betrayal of humanity” of slavery. It was also in this spirit of apology that Georgetown University, a Jesuit-affiliated institution, decided in 2017 to apologize for its role in the slave trade.

Nine of the 18 states with slave populations before the Civil War have issued official apologies. Some of the largest slave-holding states, however, have still not done so. Among the holdouts are Mississippi, which finally ratified the 13th amendment ending slavery in 1995, 130 years after the end of the Civil War, and Kentucky, which ratified the 13th Amendment in 1976.

Granted, many of the victims' descendants will deem a belated official apology sorely inadequate. Mere empty words. Indeed, how could saying "sorry" ever be enough to cure a wrong as profound as mass enslavement? It cannot. But a well-made apology can formally acknowledge America’s collective history and offer a necessary first step in righting the national conscience by affirming its principles.

Indeed, it is exactly those moments when moral courage trumped political or economic expediency — the suffragettes, the civil rights movement, same-sex marriage — that have come to define the most important American values.

The key point, morally and spiritually, is that the offering of a full and sincere apology is a redemptive act — for the nation, for all of us as citizens, including the victims. Only the president or Congress, acting as stewards of the national conscience, can make this apology.

Some contend that Americans today need not be held accountable for deeds done long ago. Such was a lot of the criticism of the New York Times’ 1619 Project, which some conservatives argued was “divisive.” Just move on, they said. This specious view, however, creates moral hazard by encouraging people and nations to shirk accountability in the hope that time will wash away the guilt.

To the contrary, all citizens, including the newest ones, inherit the entire legacy of America — good, bad and ugly. New U.S. citizens enjoy the benefits of freedom, enterprise and other unique fruits of American history. But they also shoulder shared responsibility for the national debt, for example, which they had no part in creating. Must we not also take moral responsibility for the actions of previous Americans who enslaved others in the name of our country?

It also turns out, as Faulkner wrote, the past is much closer than we think. Ta-Nehisi Coates has eloquently reminded us that the scourge of racial inequality continued long after Reconstruction — through the invidious forms of segregation of the Jim Crow era to the insidious patterns of segregation that persist. Today, African American families’ median wealth is about 10 percent that of whites.

Another standard rejoinder is that it is incorrect to judge the past by contemporary standards. This, too, is misplaced. Slavery was known to be wrong at the time. As early as 1777, for example, Vermont banned slavery. As President Abraham Lincoln put it in 1854:“No man is good enough to govern another man, without that other’s consent. I say this is the leading principle — the sheet anchor of American republicanism.”

It is also said that slavery was an institution peculiar to the South. This view misses the reality that the entire U.S. economy before the Civil War was an integrated system. Southern surpluses from the cotton trade were readily invested in the North, and Northern banks financed the Southern economy. Moreover, the drafters of the Constitution, North and South, agreed to the abhorrent Three-Fifths Compromise.

The election and re-election of Barack Obama as president was certainly a major milestone in national healing. But it was no substitute for an official apology. Pointing to the election of one African-American president in 2008 as some kind of absolution for centuries of cruelty and inequality against millions of Americans is a bizarre view of justice.

The atavistic racialist rhetoric of Obama’s successor shows that the work of atonement is far from finished. The fact that Donald Trump’s political career was built on birtherism shows this. Indeed, the country seems to be going in the wrong direction.

The idea of an apology, much less reparations, has gone up and down over the last 20 years, but is certainly on a downward trend today. Lack of public support is not surprising, because it reminds us of an ugly truth about U.S. history. But unpopularity should not deter us from a just course.

A national apology would not be the last word on righting the historical wrong — leaving open the reparations question — but it would be an essential act of contrition and a vital rededication to our American values.