The last time I spoke with my Uncle Johnny, I needed a lift. I called him on March 18, while I was working from home, just to chat and laugh at his jokes. In the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic’s paralytic hold on New York City, I really wanted to hear the comforting sound of his voice when he’d call me “Shahrzady” — little Shahrzad.

When he picked up, though, he could barely talk; in our minute-and-a-half call, he mostly coughed. I suggested that he might very well have the virus and that he should call his doctor to try to get tested for COVID-19, but he was certain it was simply regular pneumonia.

I hung up feeling anxious and unsettled. I knew testing was rare and results took days.

California’s stay-at-home order went into effect the next day; the day after that, Uncle Johnny passed out in his house and an ambulance took him to Hoag Hospital in Newport Beach. It was already too late to say goodbye. After several days on a ventilator, his heart stopped. He was only 62.

I was heartbroken and angry at how this cruel virus had suddenly ravaged his body without allowing those who loved him to visit him at the hospital — much less hold his hand. And now that he was gone, the virus wouldn’t allow the rest of us to hold each other.

I had to deliver the news to my mother in person, but I was afraid to take a bus, a subway or even a cab to see her. I decided to walk to her apartment, three-and-a-half-miles away from mine.

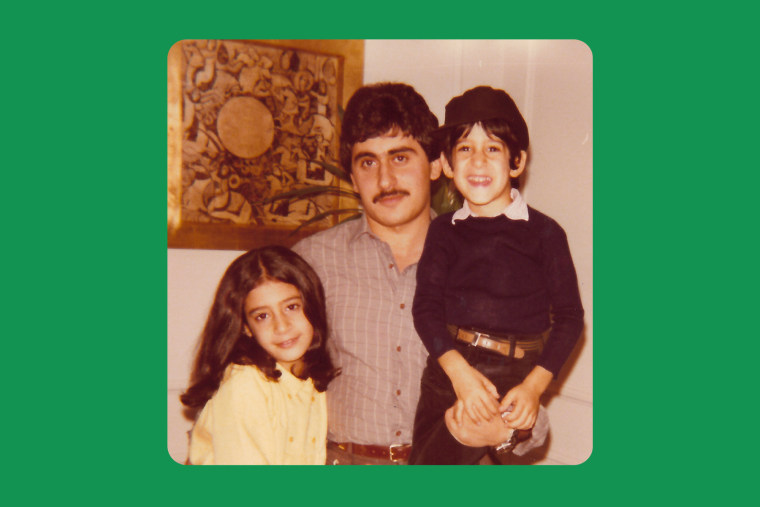

During the hour-and-a half walk through deserted streets, I could see Uncle Johnny and me back in Tehran, when I was a little girl, watching cartoons; and him at LAX, when I was a teenager, picking me and my brother up for vacations with him. I knew I could always call him for guidance or ask him for anything, and his love and generosity was boundless.

When I finally got to my mother's building, I called and asked her to meet me in the street below. All I wanted to do was to put my face on her warm cheek and take comfort in the smell of her hair. Instead, we awkwardly stood 6 feet apart and shivered in the chill as I told her. Shocked, sad and angry, we parted without hugging and she walked back inside.

I walked home, nervous about bringing the virus back with me. What would have been a bustling Thursday night in Manhattan was silent; a night my husband, Doug, and I might otherwise have been spilling out of a theater onto a swarming sidewalk was instead punctuated by ambulance sirens.

That sense of isolation — the longing to have hugged my mother, the silence of the city, the thought of my uncle dying alone — was just the beginning.

We couldn’t get on a plane to go to California to sit shiva, hold services or go to his burial — not even his sisters who live nearby, my aunts Jeannette or Mojgan and her family, were allowed. There was no one to throw flowers and rosewater on his coffin — the Iranian-Jewish way to wish a loved one a sweet afterlife — before we would normally take turns putting spadefuls of earth on top.

We could only listen to a recording of the burial while we sat shiva in New York and elsewhere via Zoom, imagining the hilltop at Eden Memorial Park cemetery in Los Angeles while the rabbi’s chants echoed. Standing over my uncle’s coffin, next to my grandparents’ graves, he recited all the prayers meant to comfort us — into emptiness, himself crying at times.

Infuriated at the situation, I imagined the virus itself chuckling at the thought that my uncle had not a single friend or family there. But our family’s resolve to band together those seven nights of his shiva drowned out all that — and our virtual shiva wasn’t as unsatisfying as I anticipated.

We recited the prayers every night; we took out old photo albums and were comforted by the faces and voices of my uncle’s own aunts — our family matriarchs. We told stories and stayed on long enough for cousins in Israel to wake up and join us. Grasping for a little positivity, one cousin commented that, in “normal circumstances,” we’d have split into different conversations, rather than being part of one together.

She was right. In the face of all the pain, we were also determined to not grieve without one another. And right there, on our screens from New York, California and Israel, we hadn’t surrendered to isolation or social distance. Resilient, we were together in a way we had never been before.