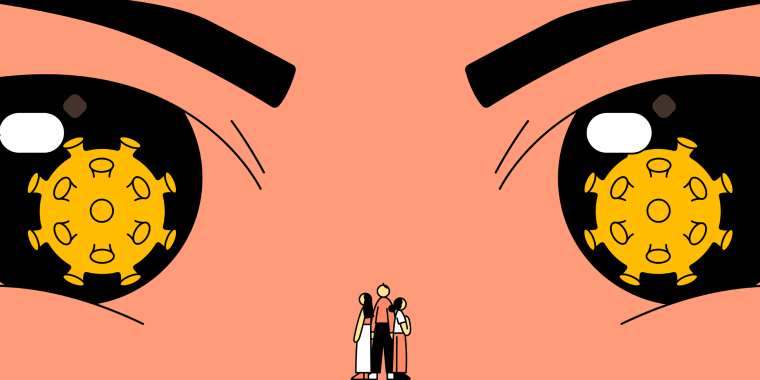

On the same day that federal health officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued a warning that the new coronavirus was certain to spread within the United States, I was on my usual morning train in New York City when the person next to me pulled out a bottle of nail polish and started painting their left hand. The fumes from the polish hit me hard and I sneezed twice in quick succession. Instantly, all eyes turned toward me. I watched the fear spread as public perception of me shifted from being a “model minority” to a “yellow peril.”

With the outbreak of the novel coronavirus, Asian Americans are once again facing hostility during a global public health emergency.

With the outbreak of the novel coronavirus, Asian Americans are once again facing hostility during a global public health emergency. While Americans have been advised by experts and officials to prepare, not panic, we also see empty Chinatown restaurants across the country, flight cancellations and travel restrictions to and from China and other parts of Asia, Asian American children and students experiencing harassment and discrimination (something I was very familiar with during the SARS outbreak in 2003), insidious misinformation that can spread far more quickly and widely than the virus itself, and a top medical journal publishing a damaging viewpoint that speculates on biological differences among Asian males based on “unconfirmed data.”

During disease outbreaks, attacks on marginalized groups are not an exception, but the norm. This racism and xenophobia is additionally stoked by discourse that casts the bodies and behaviors of Chinese Americans and other Asian Americans as suspicious and even at fault for spreading disease.

While viruses and other pathogens do not discriminate between hosts based on race, ethnicity, nationality or immigration status — stigma and misinformation certainly do.

Examples of this can be found throughout history. Jewish communities were targeted during the bubonic plague in the 1300s, Irish immigrants were blamed for typhoid in the 1800s, Haitian Americans were thought to be responsible for HIV in the 1980s, Mexican Americans for swine flu in 2009, and West Africans for Ebola in 2014. In 1906, a Chinatown in Orange County was torched and burned down while city officials watched and did nothing, citing disease (leprosy) and threats to public health as the excuse. Chinese Americans also aroused ire for SARS in 2003, and again today, for COVID-19.

But for Asian Americans, there is an extra source of irony. Here we see the contrast between the two most common Asian American stereotypes. In some instances, we are wielded as a “model minority” against other groups, particularly other people of color; in others, we are cast as “perpetual foreigners” who pose a threat to stability and order. These dually harmful, racist and pervasive stereotypes — of Asian Americans as both the “model minority” and the “yellow peril” — shape the narrative of how we can place these hostilities that consistently emerge during moments like the current outbreak in context.

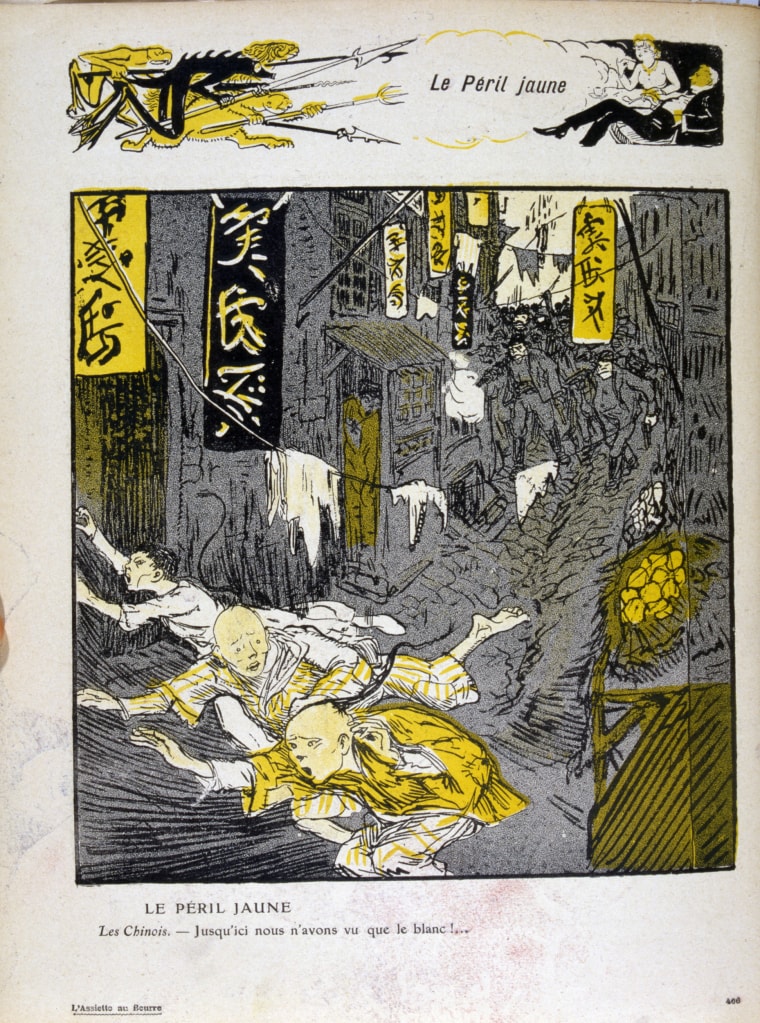

“Yellow peril” is thought to have been coined by Wilhelm II, the emperor of Germany, who commissioned a painting, completed in 1895, that became one of the most influential political illustrations at that time. It called on the “civilized” nations of Europe to defend against Asian conquest.

This anxiety has persisted in American history and culture. As Dr. Gary Y. Okihiro describes in his 1994 book “Margins and Mainstreams,” “the fear, whether real or imagined, arose from the fact of the rise of nonwhite peoples and their defiance of white supremacy. And while serving to contain the Other, the idea of the yellow peril also helped to define the white identity, within both a nationalist and an internationalist frame.”

In fact, the passage of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act was the first time the United States had ever barred a specific ethnic group from seeking immigration and naturalization.

With COVID-19, we see that little has changed — or at least, we see how easily society slips back into its worst patterns. The same “yellow peril” language and imagery is once again back in public discourse and media coverage. A French paper faced backlash over its recent front page headline that read alerte jaune, or “yellow alert.”

Seemingly in opposition to “yellow peril,” but also driven by structural anti-Asian racism, the “model minority” myth is the thoroughly debunked but still widespread stereotype that Asians in America are healthier, better educated, harder working, and more successful than other racial and ethnic minority groups. This idea is rooted in anti-Blackness, and was leveraged by a conservative white majority in the 1960s to oppose the activism of the civil rights movement. Since then, it has been consistently wielded to diminish the struggles of other racial and ethnic minorities, particularly Black Americans.

The model minority stereotype assumes Asian Americans are a monolith, instead of a group characterized by tremendous diversity representing more than 50 different ethnicities and 100 different languages. Only highlighting the wealth, health and success of a select few (à la “Crazy Rich Asians”), ignores and masks the wide range of inequality and disparities that exists, with certain Asian subgroups bearing the brunt of high poverty rates and unmet needs, and are extremely understudied and underfunded in health research. Falsely expecting all Asian Americans to be submissive, highly educated, and wealthy, is dangerous as we are told to prepare for COVID-19, especially since adequate preparation demands resources and privilege.

Recognizing and understanding the simultaneous impact of both “yellow peril” and “model minority” stereotypes, as well as the true diversity of Asian Americans, is essential. This is especially true as local, federal and global responses to COVID-19 continue to build.

Now more than ever, we need clear and effective messaging to all members of the public, including immigrant communities, on key developments in the outbreak and how to take the necessary precautions.

As a public health researcher who previously worked at the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (where I contributed to several emergency disease responses including the Ebola virus in 2014, the Zika virus in 2015-2016, and Legionnaire’s outbreaks in 2016), I can confidently say that we have known measures and emergency preparedness plans that are effective during infectious disease outbreaks.

However, as an Asian American from an immigrant family, I can also confidently say that these actions will be less than optimally effective if they don’t reach typically overlooked groups, and if they don’t acknowledge that public panic and fear fueled by xenophobia and racism are neither surprising nor unprecedented during a public health emergency. We are neither your model minority nor an outside threat, and falling into either trap will only make containing this crisis harder — for Asian Americans and for everyone.