March 2020 is the month Americans woke up and went to war with COVID-19. They can draw courage from their forebears during the pivotal month of March 1776.

Last week, President Donald Trump declared “a medical war” on the coronavirus as Americans nationwide mobilized to find and donate a critical weapon: N95 masks. These protective masks are used in high quantities by medical professionals so they can breathe safely while treating patients. As an example of how dire the need is, just one hospital, New York-Presbyterian, estimates it consumes 40,000 masks per day.

The hard truth is America’s war on the coronavirus is nowhere near finished, and we will need endurance now as much as innovation.

To meet the national shortage, private citizens began going through garages, basements and storehouses to find forgotten masks, giving them to hospitals while manufacturers such as Honeywell and GE rushed to make more. Building on the president’s rhetoric, BuzzFeed called the volunteers “a hardscrabble grassroots army” supplying “doctors and nurses on the front lines of the war on COVID-19.”

Sadly, shortages of key resources at times of crisis are nothing new (for example, rubber at the outbreak of World War II). And today’s urgent search for masks and respirators mirrors an even earlier episode from our history, as Americans in this world-changing moment are actually following in the footsteps of our original hardscrabble grassroots army — the Continental Army of the American Revolution.

In March 1776, Americans scrambled for a different national resource — firepower — and the story of how they secured it at a pivotal crossroads for the country offers inspiration for our present hard times. Like them, Americans today can rise to the occasion.

When the revolution began in 1775, it found British troops already occupying Boston and George Washington’s poorly equipped army encircling the city. While most of Washington’s volunteers had brought their own muskets, they lacked cannons. Making matters worse, the continentals faced a gunpowder shortage so dire, the normally resolute Washington was stunned speechless for nearly half an hour when he learned just how little his men had.

Without this type of serious artillery, the Americans had little hope of driving off the invaders. Worse, their inexperienced army was exceedingly vulnerable to counterattack.

Enter Henry Knox, a 25-year-old Boston resident with no military training, no previous combat experience. In fact, Knox was a bookseller, working in the 1700s equivalent of a data processing center. Much like modern-day millennials, he was an avid consumer of information and what he lacked in experience he made up for with grit and initiative.

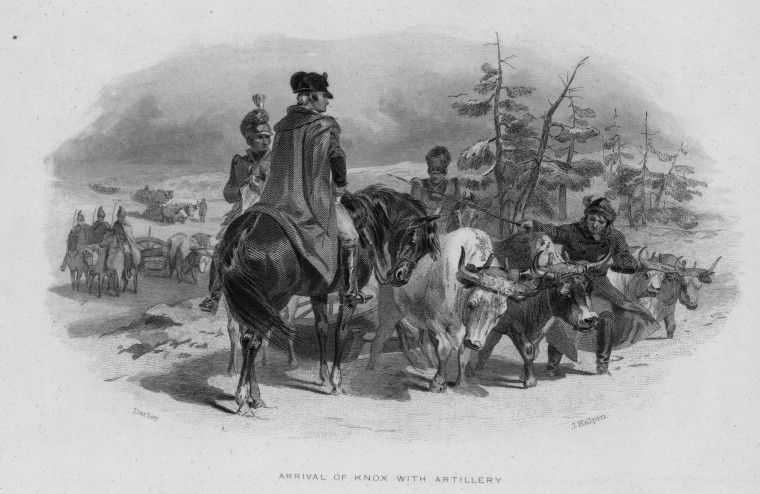

With Washington’s blessing, in late 1775 Knox led an expedition to retrieve cannons at recently captured Fort Ticonderoga in northern New York, near the southern tip of Lake Champlain. There the bookstore clerk disassembled 59 different artillery pieces and loaded them onto boats for a 30-mile trip down Lake George in the dead of winter.

Knox’s team reached the lake’s far end just before it froze solid. They then put their cargo onto wooden sleds so horses and oxen could transport it overland to Boston. Progress was stop and go, but Knox’s team hauled more than 60 tons of cannon over 300 miles of frozen rivers and mountains in 56 days.

After several days of punishing cannonades, on Saint Patrick’s Day 1776, with Knox’s guns established on the high ground above the city, Washington’s ragtag army of regular Americans forced 11,000 British soldiers to evacuate Boston by sea. The city was saved.

For a majority of Americans today, fighting the coronavirus will require nothing so physically demanding, but it will require the mentality Knox brought to the crisis in 1776: creative thinking, a willingness to take initiative and a desire to mobilize for the good of those on the front lines.

As governments and large businesses intensify their efforts, regular Americans are already demonstrating those qualities — from a couple in upstate New York who are 3-D printing face masks for their local COVID-19 testing center to a northeast Pennsylvania construction company donating its masks to health care providers.

Beyond the push for more masks, distilleries across the country have switched to making hand sanitizer. Congregants of a synagogue in the Bronx delivered pizzas to families in quarantine as Catholic priests in Maryland have begun offering drive-through confessions.

Congress may be stuck due to domestic politics, but Americans are showing that they won’t let the partisan divide keep them apart from those in need. New York Times columnist and self-described socialist Liz Bruenig announced she would donate baby wipes and diapers to domestic violence shelters for every package she bought for her own kids during the pandemic; on the opposite side of the political spectrum, Blaze Media’s Jason Howerton tweeted, “If you’re an elderly person in the [Dallas-Fort Worth] area and you’re scared and in need of groceries or supplies, DM me.”

This is America. The above examples, just like countless others in communities across this country, answer a hard question raised by sociologist Eric Klinenberg in a New York Times op-ed last week. Reflecting on the practice of social distancing, Klinenberg wrote that it was “an open question whether Americans have enough social solidarity to stave off the worst possibilities of the coronavirus pandemic.”

Idiot spring breakers aside, the answer is, “Yes, we do.”

It will be critical to remember this in the days to come, especially as the virus’s worsening impact on our country becomes clearer, from next month’s joblessness report — which is expected to break records— to far grimmer statistics on fatality rates.

The hard truth is America’s war on the coronavirus is nowhere near finished, and we will need endurance now as much as innovation. It isn’t just masks, but all kinds of personal protective equipment that hospitals are lacking. And as health care providers themselves fall ill, hospitals’ capacity to treat patients — not only for the coronavirus but the full gamut of regular health problems, from cancer to broken bones — is strained even further.

Washington’s army suffered severe defeats after its stunning victory in Boston; Americans today should expect a hard time ahead on the coronavirus, even with brilliant and compassionate actions from their compatriots. But we should not doubt our own reserves of goodness, creativity and grit.

There is an old strength in the American people that lies deeper than party affiliation, and it is available to us now, in this moment, today.

Endurance amid crisis and hardship is not just for the patriots of 1776. Or the pioneers who headed west. Or the immigrants who arrived on Ellis Island. Or the Greatest Generation that fought in World War II. It is for us, in our own time.

There is an old strength in the American people that lies deeper than party affiliation, and it is available to us now, in this moment, today. It rises like an underground aquifer when a tectonic shift occurs, as it is right now.

America, this is our moment.