Like many public transportation commuters, my daily walk to the train station, two-train transfer and four block stroll to my midtown office had been a chance to both mentally prepare for my work day and, when that day ended, mindlessly unwind. While often rushed and hardly on time, I’d usually manage to grab a coffee and a bagel, and get through a chapter or two of my weekly read while listening to music or catching up on a podcast. And I’ll admit that even with train delays and increasingly inclement weather, at the beginning of the pandemic, I missed this daily ritual.

If we are to learn something from the systemic pitfalls Covid-19 has painfully highlighted, we must listen to those who do not consider their commutes to be a time to relax.

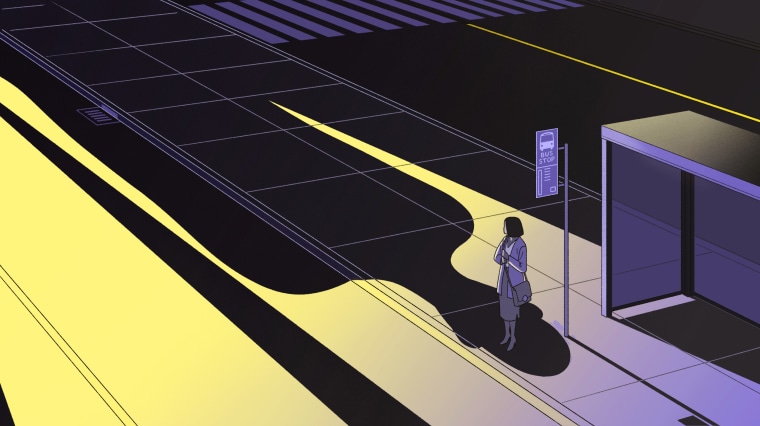

What I did not miss, however, was how often my commute was ruined by a shameless catcaller or a crude subway passenger. More than once, I was followed home by a stranger who seemed to consider harassment synonymous with a wanted compliment. When listening to music, I would use busted headphones so I could hear music with my right ear and keep track of my surroundings with my left.

Now that there’s a push for more people to return to in-person work, many are attempting to advocate for pre-Covid “office life.” There have been numerous public discussions surrounding how "healthy" commutes are and how traveling to and from work is a time to "decompress." Others have argued that working from home is more stressful than going through a daily commute, while traveling to an office provides a “buffer” between work and home life.

While that may be true for many office worker, a 2014 national U.S. survey of 2,000 people found that 65 percent of all women had experienced street harassment, 23 percent had been sexually touched, and 20 percent had been followed.

A 2019 U.K. study showed that women were more likely to quit their jobs due to their commutes than men, in part because their commutes were more stressful, often eating up time they need to manage the bulk of the childrearing and household responsibilities. Women also spend more time in traffic than men.

Holly Kearl, author of “Stop Street Harassment: Making Public Places Safe and Welcoming for Women,” found that 99 percent of 800 American women surveyed said they had experienced at least one instance of catcalling, groping or other form of public harassment, leading Kearl to declare public harassment to be a “quintessential female experience.”

And while a 2014 study found that the vast majority of Americans believe catcalling is inappropriate, 18 percent consider it to be “sometimes appropriate.” The same study found that 20 percent of Americans believe catcalling to be a compliment, and 22 percent of men consider it to be “sometimes” or “always” appropriate.

There’s also the lingering inequities inside the workplace that can make working from home more desirable. According to 2017 data reported by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 83.5 percent of harassment charges were filed by women, compared to 16.5 percent by men. A 2017 poll conducted by NBC News and The Wall Street Journal found that 48 percent of women experience workplace harassment in the form of unwanted sexual advances or verbal or physical harassment.

Of course, it’s not just women who face disparities both inside the workplace and on their way to work. A recent study from Future Forum found that 97 percent of Black professional workers want to continue working from home or use a hybrid model, in part due to racial microaggressions, discrimination and glass ceilings. People with disabilities face greater challenges both traveling to and working in an office environment, and despite the Supreme Court shoring up workplace protections for LGBTQ+ people, there are still lingering inequities and public safety issues that can make a commute to work anxiety-inducing, if not outright dangerous, for some.

Which is why blanket statements about the benefits of a commute are shortsighted and overlook the plights of many workers, to everyone’s detriments. There is a reason — likely many reasons — why 68 percent of women say they prefer to work from home, compared to 57 percent of men.

If we are to learn something from the systemic pitfalls Covid-19 has painfully highlighted, we must listen to those who do not consider their commutes to be a time to relax and, as a result of their experiences, do more to make sure everyone has the ability to travel safely to and from their jobs. With music that plays in both of their earbuds.