Until we reach the herd immunity milestone for Covid-19, when 75 percent to 90 percent of the population has been immunized through communal exposure or vaccination, we will be wearing masks, socially distancing and living in a world of glassed-off bank tellers and Lysol dependence. But one underused tool could make a significant difference in identifying and countering the virus's spread without disrupting anyone's life or surroundings: environmental testing.

By sampling and measuring the presence of virus within a given community, environmental testing can identify viral presence weeks before other measures.

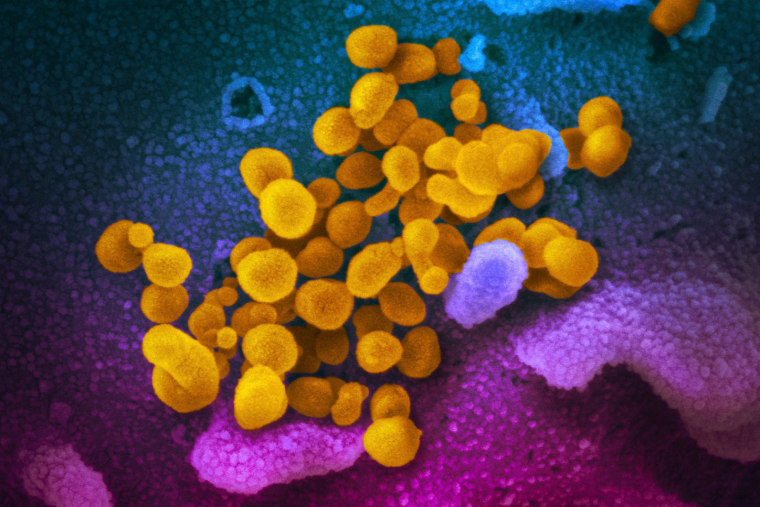

Environmental sampling is an unbiased and unambiguous approach to locating where the disease is spreading. Any person who produces virus — symptomatic or asymptomatic — spreads these viral particles into the environment. Most will be inactivated because of the harsh conditions outside the human body. However, as we have seen in tracking the rapid spread of the virus around the globe, some particles remain infectious on surfaces and in the air.

By sampling and measuring the presence of virus within a given community, environmental testing can identify viral presence weeks before other measures, such as contact tracing. Among the benefits, that allows health care groups to localize outbreaks and employ targeted contact tracing in these areas.

Environmental testing has traditionally been a staple tool in investigating viral outbreaks, providing early recognition and tracking new cases. During the 2013 Netherlands measles outbreak, environmental sampling was able to correlate quantities of virus in common water samples with the number of clinical cases. When polio outbreaks were being tracked in Pakistan, environmental testing located outbreaks of polio four months before the development of symptoms.

The last year has also shown the potential for scientists to home in on new Covid-19 cases in our communities and hospitals. Sewage sampling across college campuses and cities, for instance, has been demonstrated to act as the proverbial canary in the coal mine, revealing the silent presence of viral particles. This allows a smaller proportion of the population to be tested individually to identify and quarantine people shedding virus before disaster strikes. Surface and air samples provide similar "footprints" of where recent viral shedding has occurred.

Despite its potential to pinpoint problem hot zones of transmissions, whether in hospital settings or in business complexes, there has been no push to incorporate viral sampling into the national viral surveillance strategy. Thus far, the U.S. plan to prevent Covid-19 has focused primarily on social containment and contact tracing.

Social containment rests on the willingness of the greater population to stringently follow rules about masks, social distancing and quarantining. Contact tracing, alongside surveillance techniques such as symptom checks, ignores the dangers of people who spread asymptomatically. Environmental testing, however, can create sweeping, continuous surveillance that provides community-tailored yet anonymous results.

The primary obstacle preventing widespread environmental testing is a lack of investment in the development of sensitive detection methods. This can be overcome with the same ingenuity that our scientific minds brought to bear in developing Covid-19 rapid testing, antibody tests and, ultimately, vaccines.

Until then, there are several opportunities for states to implement this essential tool without sophisticated new devices. As the government considers Covid-19 relief fund allocation, some of these resources should be used to hire virus hunters for the simple and inexpensive process of swabbing surfaces, collecting sewage water and air samples and delivering the materials to laboratories to quantify viral shedding in key regions.

By using environmental sampling of locations at risk of high spread, such as schools and nursing homes, contact tracing regimens could focus on new outbreaks before systemic viral spread occurs, and public lockdowns could be limited to areas with confirmed outbreaks.

Similarly, hospitals strive to maintain treatment for those sick with common diseases while providing optimal care for the new surges of Covid-19 patients. Without implementing environmental sampling to trace viral dispersion, many facilities are flying blind in terms of what type of protection is needed and where to focus their resources.

By making environmental testing part of our arsenal against this virus, we can create safer environments for patients seeking essential medical care, localize key sources of spread within our community and identify when novel strains pose new risk of systemic spread.