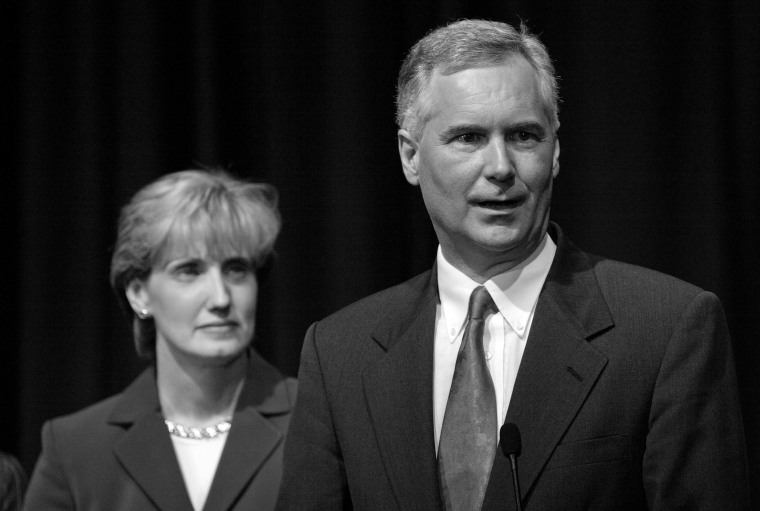

Some 58% of Americans report taking dietary supplements, often motivated by a wish to “improve” or “maintain” health. But the death of Lori McClintock, wife of U.S. Rep. Tom McClintock of California, is a tragic reminder that dietary supplements aren’t always good for you.

A report recently obtained by Kaiser Health News revealed that McClintock died from dehydration ultimately caused by ingesting white mulberry leaf, generally advertised as promoting weight loss and available in forms like pills and tea. Deaths from white mulberry leaf appear to be rare, and we don’t know the form McClintock consumed the leaves in or if they’d been sold to her as a supplement. But they commonly are, and if that was the case here, it would be far from the first death caused by dietary supplements.

Many dietary supplements aren’t what they say they are, or contain harmful ingredients.

Basic regulations are needed to make sure these kinds of supplements, which include herbs, probiotics and vitamins, are safe and effective. Unlike prescription or over-the-counter drugs, supplements are treated more like food, meaning that regulators step in only after a problem is reported — which creates a lot of space in which things can go wrong. Many dietary supplements aren’t what they say they are, or contain harmful ingredients.

The Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 states that dietary supplements aren’t required to undergo any testing to make sure they are safe before being sold. Instead of the Food and Drug Administration testing substances in advance for safety, supplements are assumed to be safe until shown otherwise. If your doctor wrote a prescription for a medication that may or may not have been tested for human safety, you’d probably think twice before you headed to the pharmacy. But that’s the very real position people find themselves in when they walk into an aisle full of vitamin extracts and weight-loss pills.

Sadly, while white mulberry leaf is generally safe, other supplements are not. A 2015 study found that about 23,000 emergency room visits every year are caused by dietary supplements. In the case of body-building supplement OxyELITE Pro, dozens experienced severe hepatitis and liver failure, and several people died after taking it.

And a 2002 congressional report found that supplement producer Metabolife had hidden almost 2,000 reports of damaging side effects from the FDA and consumers, including strokes, seizures and heart attacks. (Metabolife claimed it hadn’t received any reports of adverse effects connected to its products, although the FDA banned ephedra, an active ingredient in Metabolife’s popular supplement, and multiple legal decisions have deemed the product to be dangerous.)

Supplements often aren’t even what they say they are. Imagine ordering a BLT sandwich and getting something that looks like a BLT but doesn’t actually have any bacon, lettuce or tomatoes. This isn’t likely to happen because we are familiar with bacon, lettuce and tomatoes, but people are usually unfamiliar with the specific ingredients claimed to be in supplements. Do you know what a pill containing white mulberry leaf extract looks like? I don’t.

A study on ginseng supplements found that 12% of ginseng products procured from the U.S., for instance, weren’t made from the kind of ginseng listed on the label. Another study found that a quarter of black cohosh supplements didn’t have black cohosh in them. Even promoters of supplements themselves admit that mislabelling is a problem.

Sometimes supplements also come with unwelcome surprises — such as hidden prescription drugs. After athletes began unexpectedly failing drug tests and blaming their workout supplements, scientists took a look at the chemical composition of one called Craze. The name was fitting given that it contained a new analog of methamphetamine. People taking workout supplements usually want to become stronger athletes, not paranoid meth addicts. (Driven Sports, the company that produced Craze, claimed it did not contain a methamphetamine analog and was “safe and effective,” although it was still pulled from the market.)

Earlier this year, the FDA alerted consumers to honey-based sexual enhancement pills that secretly contained sildenafil and tadalafil, the active ingredients in Viagra and Cialis. Such “special ingredients” aren’t uncommon. The FDA’s Health Fraud Product Database lists hundreds of supplements that secretly contained tadalafil and sildenafil.

This doesn’t sound as bad as Craze (after all, these pills might actually do what they’re advertised to do), but unlabeled prescription drugs can still have potentially lethal side effects if taken at the same time as other drugs; sildenafil may cause problems if taken with anything from alpha-blockers to vericiguat, for example. A competent doctor prescribing sildenafil would make sure it doesn’t interact with other medications, but doctors and patients can’t check for dangerous drug interactions if they don’t know what they’re taking.

Voices as varied as the Hoover Institution and comedian John Oliver have called for the FDA to have the power to regulate dietary supplements, but a major reason that hasn't happened was the opposition of former Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, who championed the legislation that deregulated supplements and for decades fought against efforts for sensible rules. Though he died earlier this year, the supplement industry’s lobbying money remains a powerful obstacle to stronger regulation.

The Senate is currently considering the Dietary Supplement Listing Act of 2022, which would require supplements to be registered with the FDA, and to list their ingredients. That would be an improvement, but we’d still need another bill that requires supplements to be tested for safety and effectiveness before going on the market, similar to the prescription drug approval process.

The FDA has to wait for the next time people report a shady supplement to act, but we don’t have to wait to show our support for laws that would regulate supplements to make sure they are safe and effective before people get sick yet again.