If you’re old enough to remember the Cold War, maybe you think of democracy as sacrosanct, an often-endangered ideal worth fighting for. But if the Berlin Wall was before your time, you might not take the value of democracy as given. That’s one conclusion that can be drawn from recent studies that suggest young people are not as sold as their parents and grandparents were on this most basic of American ideals.

According to a study published in October 2017 by Pew Research, there’s a division of opinion in many countries today on whether states are more effectively governed by “experts” or elected officials. In advanced economies, young adults are more likely than older people to prefer technocracy to democracy. The study found that in the U.S., 46 percent of those aged 18 to 29 would prefer to be governed by experts compared with 36 percent of respondents aged 50 and older.

A study from Harvard’s Yascha Mounk and the University of Melbourne’s Roberto Stefan Foa published in the Journal of Democracy in January 2017 produced an even more striking result. Just 19 percent of U.S. millennials agreed with the statement that “military takeover is not legitimate in a democracy.” Among older citizens, the total was a still-surprising 43 percent. (In Europe, by contrast, the corresponding numbers were 36 percent for younger people and 53 percent for older people.) Perhaps most alarming was the revelation than one quarter of millennials agreed that “choosing leaders through free elections is unimportant.” Just 14 percent of Baby Boomers and 10 percent of older Americans agreed.

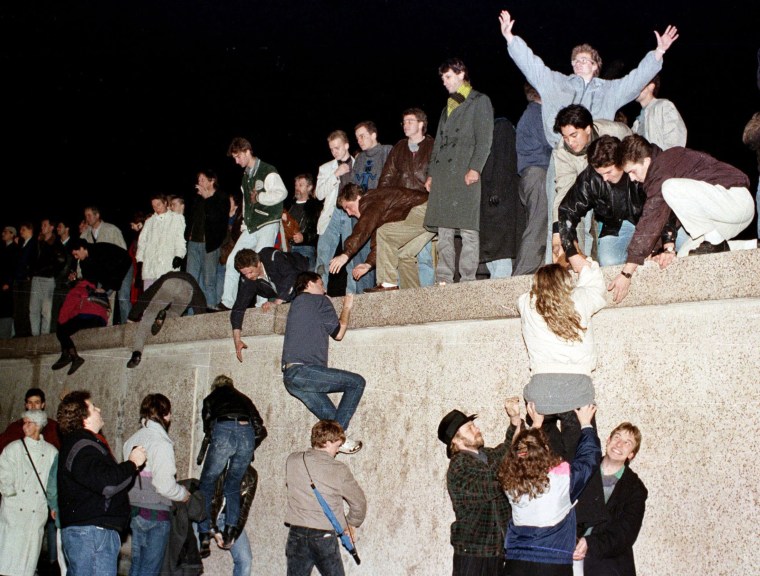

Those of us over 40 wonder what’s going on. Maybe it’s that young Americans — and Westerners generally — have grown up without a fascist or communist enemy to pose an existential threat. The Berlin Wall has now been down longer than it was up, and no one under 35 will remember a time when unauthorized passage from East to West Berlin would get you shot. In a world where even the Communists are no longer communists (China’s state-capitalism is a far cry from Marx, to be sure), there’s no competing ideology forcing those who live in democracies to consider what life might be like without it.

Or maybe it’s that democracy in America no longer seems to be working. During the 1930s, economic depression led many to look abroad for alternatives to democracy and free-market capitalism. American millennials have never stood in a bread line, but they have experienced the most severe financial crisis since the 30s, a dramatic widening of the gap between richest and poorest, a hollowing out of the middle and working classes, and a level of dysfunction and petty partisan hostility in Washington that seems to get worse by the week.

Maybe the problem is that young Americans — and Westerners — have grown up without a fascist or communist enemy to pose an existential threat.

Then there’s the Trump effect. An NBC News/GenForward poll published in January found that 63 percent of millennials disapprove of the way President Donald Trump is doing his job. And 46 percent strongly disapprove. It’s harder to make the case for the American way of government when a president who many millennials abhor trashes their values with each tweet. And why should a younger generation that faces bleaker economic prospects than their parents invest in the “American Dream?” It’s hard to make the case for “free trade” when trade deals combine with new technologies to kill good jobs.

This isn’t simply an American phenomenon. The Mounk-Foa study found that the percentage of people who say it’s “essential” to live in a democracy falls sharply from older to younger people in many other Western countries. And for more conservative young people, a heightened global awareness of terrorism and the global flows of refugees creates deep unease in countries where democracy may make immigration and border controls more difficult.

Perhaps new technologies are also playing a role. The power of the individual to broadcast an opinion to the world has promoted something of a backlash against free speech online as those threatened by debate or wedded to politically correct expression devalue the open debate central to democracy’s appeal. Maybe the filter bubble, the automated compartmentalization of news and views online, has captured enough millennials to persuade them that free speech has become an illusion and that democracy can no longer effectively defend it.

Finally, who is leading the fight for democracy? The American president hasn’t really been “leader of the free world” for a very long time because, in a post-Cold War world, few outside U.S. borders still look to Washington to defend individual freedom. It’s not simply that Trump has jettisoned high-minded rhetoric about America’s global fight for freedom in favor of a much more transactional approach to relations among nations. Those lofty ideals sounded like wishful thinking in the mouths of presidents Barack Obama and George W. Bush, as well.

Those of us who still believe citizens should only be governed with their consent are left to wonder what it would take to persuade a younger generation that we’re right. Sadly, it will probably take a crisis — one in which we’re all forced to contemplate less appealing alternatives.

But this is not the Cold War. Fascism and Communism are dead. The real crisis for democracy looks much more likely now to originate from within.