Sometimes the future is easy to predict. For instance, at Thursday night’s Democratic debate, candidate Andrew Yang is almost certain to fret about the possibility of a robot takeover. Yang's outsider campaign has been fueled by the fear that artificially intelligent machines are coming for our jobs, leading to his urgent demand that we start preparing— now!

And his techno-pessimist vision has started to infect other candidate platforms. Last week, struggling aspirant Bill de Blasio sought attention by proposing a “robot tax” that would force companies to get permission before automating any processes and then bill them for displaced workers.

This dearth of worker-replacing robots is not a reason to sigh with relief. It’s bad news! If we want to get richer as a society, we need productivity growth.

But don’t believe these Cassandra cries. If anything, what America needs is more robot workers, preferably flanked by other efficiency-enhancing changes to boost workers' wages and make our economy more productive.

How do we know that the problem is too few robots, not too many? Check the numbers. If America were being overrun with job-killing robots, it should already be leaving a distinctive and unmistakable mark on our economic statistics. That’s just not happening. And while we can’t rule out the possibility that this fear may materialize someday, that uncertain “someday” is a weak plank on which to build a presidential run given the urgency of issues like climate change and inequality that are already upon us.

In a world of invading robots, you'd expect to see an epidemic of unemployed workers — but right now the unemployment rate is at a 50-year low. And there’s no exception for those industries considered most vulnerable to robot incursions. The unemployment rate among U.S. manufacturing workers, for instance, is lower than the rate for the economy as a whole.

More important, if companies everywhere were switching from workers to machines, you should see a huge increase in productivity, and we’re not. Take the classic example of a widget-making company. By purchasing a bunch of sophisticated widget-making robots, it should be able to produce more widgets than before with the same number of workers. And if companies around the country were following this script, there’d be a general increase in the amount of stuff being made per worker.

But that’s not happening. The U.S. government has a longstanding measure of output-per-hour-of-human-work called labor productivity. And it's actually at a pretty low ebb. Since the financial crisis, productivity has increased by less than 2 percent per year, which is not just far slower than the 3-4 percent increases of the early 2000s but actually makes ours one of the weakest periods for productivity growth in the post-World War II era.

What’s more, despite the broad, self-satisfied sense that we are living in an age of unprecedented innovation and disruption, there’s a strain of recent research suggesting that breakthrough innovations (think tractors, transistors, antibiotics) are actually getting rarer and more difficult. Counting all the dollars and hours, recent advances in computing, agriculture and pharmaceuticals have required vastly more resources than the game-changers of yesteryear. Perhaps the clearest example is Moore’s law — the famous pattern by which computing power doubles roughly every two years. By one estimate, keeping up that pace requires 18 times more researchers today than it did in the early 1970s.

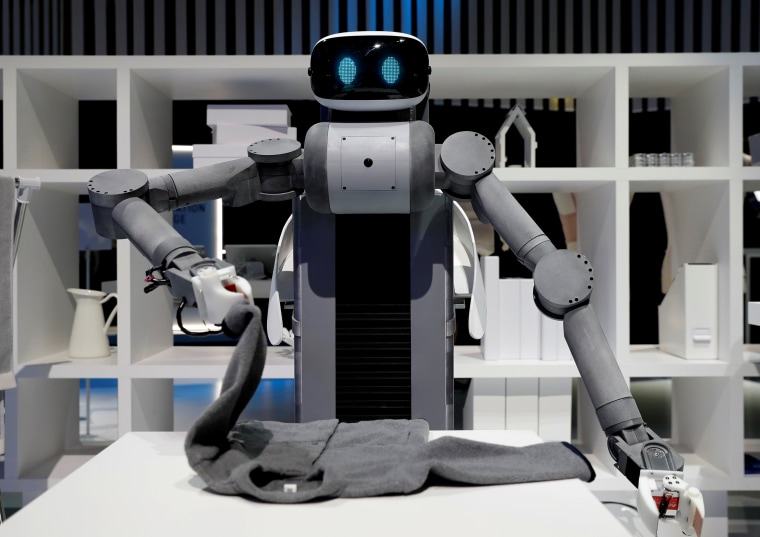

Now, this is not to suggest that industrial robots are somehow a figment of the collective imagination. They are very real and you can easily find examples of companies embracing their potential, like Amazon with its warehouse workhorses or the tireless robotic arms at auto manufacturers. It's just that these kinds of anecdotes don't add up to a nationwide economic transformation. Not yet, anyway.

But remember: This dearth of worker-replacing robots is not a reason to sigh with relief. It’s bad news! If we want to get richer as a society, we need productivity growth. In fact, that’s practically definitional. What makes societies richer is their ability to build better tools, improve worker performance and generally figure out ways to do more with less sweat: creating more goods and providing more services without having to work more hours.

And before you carp about how only the robot owners or the top 1 percent will benefit, rest assured that doesn’t seem to be the pattern. Companies that add robots tend to create more jobs, in part because those robots allow them to outcompete competitors and then hire new employees to manage the resulting growth. And while some of those new jobs will undoubtedly involve higher-skill workers, there is an imperfect but still real and time-tested connection between economy-wide productivity growth and wage growth for regular workers.

So forget Yang, de Blasio and their worries. The "fear the robots" narrative just doesn't make sense in the current environment, where jobs are plentiful but productivity growth lags. Maybe someday advanced robots and artificially intelligent entities will fulfill the science fiction fear that's been percolating since the 1870s, when Samuel Butler wrote his tale of a society where machines can do everything without us. But when that’s no longer fiction, we won’t have to speculate about whether it’s happening; we'll see it in the data.

In the meantime, we need more robots, more automation, more innovation, more worker training — all the things that allow us to do more with every hour of our working lives. That's the only way to generate real wage gains and improve the standard of living across America and around the world.