The visceral antipathy many Americans feel toward President Trump has frustrated Republicans and rallied Democrats into a frenzy of political activism. Paradoxically, it could also offer both sides an opportunity to break through the polarization that has paralyzed Washington. Rather than retreating to their own corners and preparing for battle, as so often happens before contentious elections, both Republicans and Democrats should capitalize on the public’s outrage by working within their own parties to engage the center and marginalize the extremes between now and November 2018.

Democrats would be wise not to misinterpret their recent electoral success as a sign that a leftward surge is the only way to be successful. In fact, recent history has made it abundantly clear that such a move would be disastrous for the party.

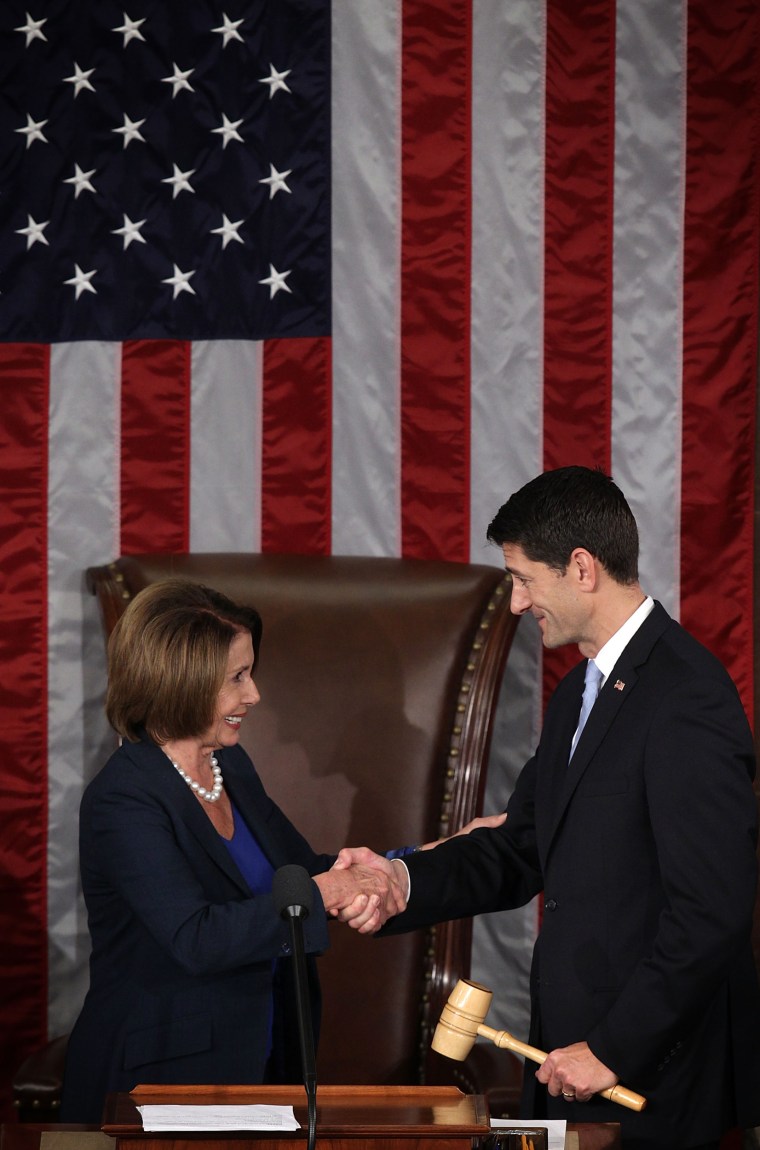

With momentum and voter enthusiasm on the side of the Democrats, it is possible that the 2018 election could result in the speaker’s gavel being placed back in hands of Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi. If past is prologue, however, this development is unlikely to limit the extreme polarization that has driven a wedge between the parties and made bipartisan cooperation seem like little more than a pipe dream. Pelosi has said she plans to use similar tactics over the next year as she did leading up to the 2006 election — tactics that worked with ruthless efficiency but which led to a deepening of the partisan divide on Capitol Hill.

Rather than exacerbate the already toxic polarization in Washington, a more prudent move for the party would be to recognize that Democratic candidates must fit the districts they hope to represent. Candidates in rural and conservative areas must tailor their message to appeal to their unique constituencies. Supporting these types of candidates — both before and after their election — might not unite all Democrats under one unified banner, but it could help bridge the partisan divide while advancing the more progressive agenda Democrats hope to achieve.

Candidates in rural and conservative areas must tailor their message to appeal to their unique constituencies.

The potential electoral wave of 2018 is taking shape in exactly the same way as the 2006 wave that gave Democrats control of the House for the first time since 1994. But Democrats should be wary of repeating the same mistakes that cost them the majority after only four years in power — mistakes that helped create the Tea Party and led to an astonishing 63-seat loss for House Democrats in 2010.

I learned these lessons firsthand as a Democratic candidate in a Republican-leaning swing seat in 2006. During the hard-fought campaign before the election, as I and dozens of other centrist candidates around the country were making the case for bipartisanship and moderation in Congress, Pelosi was working overtime to divide the parties into two warring factions. Believing it was politically advantageous to draw a clear contrast between the parties, Pelosi urged Democratic House Members to stand in uniform opposition to key Republican initiatives.

During this time, some liberal advocacy groups took this strategy a step further by threatening primary challenges against incumbent Democrats who worked with their Republican colleagues, going so far as to air a negative ad against Democratic Congressman Allen Boyd. Boyd represented a Florida district that had overwhelmingly supported President George W. Bush only months before.

As a candidate engaged in a fierce battle to win a competitive seat, I took note of the fact that the type of Democrat many liberal groups seemed to be opposing — thoughtful centrists willing to work with both sides in search of bipartisan solutions — was exactly the type of Congressman I planned to be. Yet Democrats won control of the House that year in a wave dominated not by the progressive left, but by centrist candidates who had campaigned against polarization in Washington.

As the new Congress convened in 2007, labor unions and liberal activists combined to form a new outside group — a Super PAC known as Working For Us — that was specifically designed to do for Democrats what the Club for Growth PAC has done for Republicans. Club for Growth incentivized candidates and incumbents to move away from the political center and gravitate toward the ideological extreme; Working For Us vowed to promote and fund primary challenges to any Democrat who voted “to undermine the progressive economic agenda.”

Within a matter of months, the chairwoman of the House Progressive Caucus was already calling for primaries against her moderate Democratic colleagues — some of the very people who were responsible for Democrats being in the majority in the first place. All of this helped cement a culture on Capitol Hill where compromise is a dirty word and bipartisan cooperation is considered a treasonous act to those on the ideological extremes.

After losing the majority, the remaining centrist Democrats were targeted by extremists within their own party.

The result was predictable. After losing the majority, the few remaining centrist Democrats who, like me, survived the 2010 tidal wave were targeted for defeat by extremists within their own party. Now, having purged from the House the centrists within their midst, the House Democratic Caucus speaks with a particularly unified voice because the moderates who served as bipartisan bridge builders occupy fewer seats in the room.

Today, Democratic congressional candidates like Paul Davis in Kansas, Gretchen Driskell in Michigan and Dan McCready in North Carolina are again moving themselves toward the political center in order to compete in the kinds of purple swing districts that have eluded Democrats for decades. Nevertheless, Senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, emboldened by the “mandate” they believe occurred in the recent off-year elections, have drawn praise from the progressive wing of the party by rejecting moderation and calling for an even more liberal agenda.

If Democrats want to win back the House, they are going to have to accept the fact that a critical mass of successful candidates will have to come from districts where thoughtful moderation is necessary for survival. If they want to keep the majority thereafter, Democrats will have to resist the temptation to repeat the same mistakes which led to their resounding defeat after voters entrusted them with the gavel.

The wave of discontent the American people feel toward an historically unpopular President is gaining strength. This gives both parties the opportunity to demonstrate that their leaders are willing to listen to the majority of Americans who support rational policy and bipartisan compromise. With the wind at their backs, Democrats should stop searching for that elusive “unified message” designed solely to win elections. Instead, they should seek a message of unity to help bring the country back together.

Jason Altmire (D-PA) served in United States House of Representatives from 2007-2013. He is the author of the new book “Dead Center: How Political Polarization Divided America And What We Can Do About It."